Daniel Day-Lewis on going back in time for Spielberg

Time Out meets the British actor tipped for an Oscar for ‘Lincoln’

It’s November in New York City, two weeks after Barack Obama’s re-election, and a severe, unmissable photo of the British actor Daniel Day-Lewis as another American president, Abraham Lincoln, is buzzing about Manhattan on the top of yellow cabs. There he is, time and time again in reverential black and white as the title character in Steven Spielberg’s new film, Lincoln. Day-Lewis is floating around the city like a political ghost: eyes down, hair greying, Lincoln’s famous chin-strap beard tipped as if to tickle the scalp of the taxi driver below.

Spielberg trades in the odd iconic image in Lincoln – that famous beard silhouetted in the night – but Day-Lewis plays him as a curious, persuasive mix: canny politician, rural lawyer in the big city, loving husband, bereaved father, entrancing storyteller, flat-footed and physically awkward. ‘He looked like a bag of hammers to most people,’ is how Day-Lewis describes Lincoln, laughing, when we meet in a hotel by Central Park. ‘He considered himself to be hideous and made numerous comments and jokes about himself.’

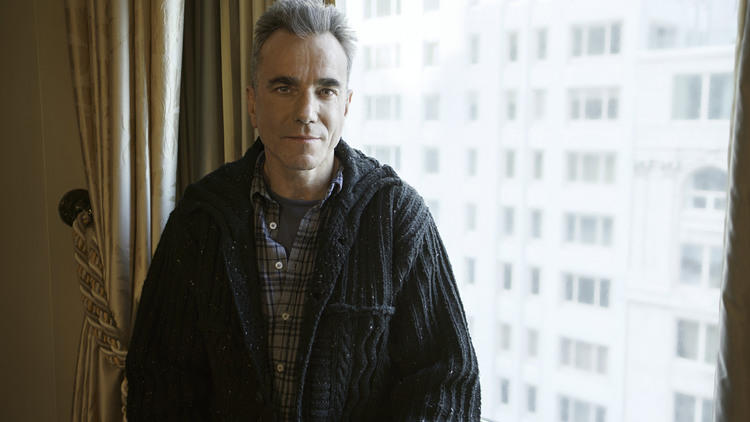

Today, Day-Lewis has left the hammers at home: he has houses in Ireland and New York, but it’s the latter where he spends more time these days after a number of years living just outside Dublin and raising a young family. He’s clean cut, stately, respectable even: he has a tidy, short stack of greying hair, and is looking youthful and lean for 55. He’s wearing a blue shirt, dark trousers and trainers and has dumped an elegant blue overcoat and silk scarf on a windowsill of the hotel room. Day-Lewis is thoughtful and jolly in conversation, if a little guarded at first.

The actor is known for the months and months of preparation he puts into each role and for carrying characters around with him while shooting: with every film come the inevitable tales of extreme behaviour, many of them framed spitefully as accounts of actorly prissiness and thespian self-indulgence. Clearly the last thing he wants to do is push that reputation further with careless talk.

‘I’ve been reluctant to talk about how I work because I don’t really feel one should talk about it,’ he reasons. ‘But I suppose the problem with that is then a lot of other people talk about it on your behalf and by a process of Chinese whispers it sounds like some strange Satanic ritual is taking place or whatever, with the whole thing about immersion and the method and all the weight that those terms seem to carry.’

His Lincoln is hugely compelling and, above all, convincing in that he looks like flesh and blood, not a hard-to-reach figure from history. He talks of the trepidation with which he approached playing him. ‘It was like grandmother’s footsteps,’ he says. ‘Because of all the monuments, the hard part is to discover the man. That’s probably why I resisted.’

For almost a decade, he said no to Spielberg’s approaches. ‘I thought: perhaps it’s not possible or right to bring this man back to life again.’ But already, only two weeks into the movie’s US release, critics are saying that Lincoln is Spielberg’s best film in years and pundits are reckoning that Day-Lewis will win a third Best Actor Oscar for his role in it – an award to sit alongside his wins for 1989’s My Left Foot and 2007’s There Will Be Blood. It would be a record; no male actor has done this before.

The film is talky, enthralling and steeped in high-stakes political manoeuvrings around the abolition of slavery and the end of the American Civil War. It takes place over the final few months of Lincoln’s life, in 1864 and 1865, and also stars Sally Field as Lincoln’s wife, Mary, alongside a sprawling ensemble of malefactors hiding their renown beneath beards and hairpieces. The film’s enthusiasm for the power and possibility of the political process is infectious.

When I see the film in a Times Square cinema in New York on a Friday night, there are whoops from the typically ethnically mixed New York audience at talk of racial and sexual equality and big applause when the credits roll. I tell Day-Lewis of this reaction from the crowd. He’s pleased, but nervously so, as if I’m going to tell him in the next breathe about someone booing the movie.

Day-Lewis occupies a deeply unusual space in cinema. He’s a leading man – a man on the cusp of winning more leading-role Oscars than any other and with celebrated starring roles in Gangs of New York, The Last of the Mohicans, The Age of Innocence, In the Name of the Father and more behind him – and yet if you stood him in a room next to other successful, middle-aged British actors – Jude Law, Daniel Craig, Clive Owen, Colin Firth – he’d no doubt be able to slip away quietly and unnoticed.

That’s partly to do with the roles he picks: those flights into other eras and extreme personalities. He barely ever plays contemporary characters, let alone people that bear even the slightest similarity to himself: he inhabits other people entirely, preferring to explore the extremes of human experience, men like the terrifying Bill the Butcher in Gangs of New York or the psychopathic Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood.

American characters that tap into the founding of the nation seem especially to draw him in. Is that what he thrives on? Exploring lives totally removed from his own? ‘I think quite honestly, yes,’ he says. ‘That is invariably the thing that finally appeals to me. The less I know about someone and the less connected I feel to them on a personal level, the more intrigued I am in the process of discovery. Which isn’t to say that one isn’t always looking for points of communion, because they’re vital.’

His relative lack of celebrity keeps him anonymous too: he might star in renowned films, pick up big awards, be the son of famous parents (the poet Cecil Day-Lewis and the actress Jill Balcon) and have married into a literary-artistic dynasty (his wife, Rebecca, is a novelist and filmmaker and the daughter of playwright Arthur Miller), but he tends to disappear from view between making and promoting his films. He’s British born and educated, but for well over a decade he’s lived most of his time in Ireland and America, with his wife and their two young sons. ‘I suppose during times like this, when your face ends up on top of a taxi you occasionally become a public figure, whether you like it or not,’ is his own brief spin on his fame or lack of it.

Of course there’s the other thing that sets Day-Lewis apart from other actors and fuels the fire of speculation about him: the aura of the ‘method’ he carries around with him from film to film. It started with stories of him living in a wheelchair for months to play Christy Brown in My Left Foot and of existing in the Alabaman wilderness for weeks before playing Hawkeye in The Last of the Mohicans, and continues right through to accounts of him insisting he was called ‘Mr President’ on the set of Lincoln (as proof of how these things are distorted in reports of him, it later emerged that it was Spielberg, not him, who suggested that way of working).

How does he feel about the man-of-mystery tag all this leads to? ‘I didn’t go looking for that,’ he says. ‘It was certainly not my intention to create a specious air of mystery about what I do. But what’s completely misrepresented is the fact that I take a long time [preparing each character] because I enjoy the work and it pleases me to take time over it. It’s pure joy for me. It’s joyful work, even when the work takes you into not particularly easy areas. There’s huge pleasure in discovery, so it’s a joyful thing. It’s a game, and I’ve never thought to obscure that fact. But, for whatever reason, that image persists of some sort of lonely, strange figure going about an unholy business.’

So what business, holy or not, did he go about to prepare for Lincoln? Firstly, he explains, time was of the essence. ‘I asked for a year, and we gave ourselves a year to do this.’ Then came the reading, starting with Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book Team of Rivals, the biography on which the film is based. ‘The hard thing is to choose what to read,’ he goes on. ‘I could still be reading now and for the next fifteen years and not make a dent in the literature about that man.’

You know he’s not talking about a quick scan of Wikipedia either. At one point in the film, Lincoln briefly quotes the Greek mathematician Euclid. Watching this scene, I’m thinking: I bet Day-Lewis got stuck into Euclid’s writing. And so he did. ‘Did you learn any Euclid at school?’ he asks. I shake my head. ‘Nor did I, but I started trying to. It’s very hard! I barely arrived at the footslopes of understanding.’

He talks about his research beyond books: he finds it easier to explain what he doesn’t do than what he does. ‘The one thing I absolutely don’t do is dismember the life into its component parts, like a mechanic, and then try and bolt it all together and hope that it functions,’ he offers. ‘I try to approach it all more or less at the same time.’

There’s been a lot of talk about the voice he adopts to play Lincoln, a soft, slightly high, conversational lilt that draws people in rather than declaims to them. It works: it’s both warm and steely, and it stresses Lincoln’s famed personality as a storyteller. How did he find it? ‘The voice is such a deep personal reflection of character that I wouldn’t even attempt to find it for a considerable period of time,’ he reflects. ‘If I’m really lucky, I begin to hear a voice. That has always been part of my experience - listening for that sound of the voice in my inner ear. If that pleases me, and I live with that for a while and the internal monologue feels right, then I go about the work of reproducing it. Lincoln always spoke aloud when he read, so that was a lovely clue. I read a lot, I talked to myself a lot.’

So where does all this solitary work leave his collaborators? Surely his Lincoln is only part of the deal? What about Spielberg’s Lincoln? What about the writer Tony Kushner’s Lincoln? ‘It’s a fair question. We had a wonderful triangular communication during the course of that year. Not that they ever asked me where I was going. I did at one point, very late on, send a tape of the voice to Steven. I’m not sure what I’d have done if it confused him because at that stage it was very familiar to me. I sent it with great trepidation and drew a skull and crossbones on the envelope saying that no one else should open it!’

He’s full of enthusiasm for Spielberg. ‘I liked him from the moment I met him. It’s always remarkable to find a degree of freshness and enthusiasm, which appears to be completely undiminished by time. There are a lot of casualties [in the film industry], people who have lost their appetite but because it’s what they do, they keep doing it.’ Does he fear losing his own appetite as an actor? ‘I think so, yeah. What I don’t fear is the possibility that I might carry on working as an actor if that proves to be the case. Because I wouldn’t. I would go and find something else to do.’

He tests his enthusiasm thoroughly each time a job comes round. ‘You’ve got to be like a greyhound in the slips at the beginning of a job because you’re sure as hell going to be crawling by the end of it.’ How does he test it? ‘It’s just a sense, a feeling. It’s that feeling of something being irrevocable. You’re drawn with such a powerful or irresistible force into the orbit of another life.’

I ask if he takes succour from reviews and prizes. ‘I don’t go looking for reviews quite honestly, but they tend to find you, both the good and the bad,’ he says. ‘Strangely, people will encourage you to look at both. I guess I’m a sucker, though not in your sense. I’m a sucker when people say nice things, and it’s unpleasant when people write unpleasant things and I’m still sensitive towards that.’

He shows some of this sensitivity when I make a comment about his make-up in Lincoln: you can spy a growing hint of Lincoln’s weariness in Day-Lewis’s make-up. ‘Don’t say that!’ He’s screwing up his face. He hates the idea that an awareness of his make-up undermines his performance. I shouldn’t have mentioned it. ‘No, it’s important, it’s important to mention it, it is actually.’ He admits I’ve hit a sore spot. ‘Ageing make-up is a dangerous thing,’ he argues, adding that it’s the first time he’s agreed to wear it on screen. ‘I had a huge resistance to it. One often sees it on film and thinks: Wow, that looks amazing.’ He sighs. ‘And, of course, then you’ve already lost the battle.’

It’s impossible not to warm to Day-Lewis: he speaks lucidly and carefully, his voice rolling on soft waves of stresses and beats. He laughs a lot too, which tempers the seriousness of his introspection. Just as his voice in Lincoln demands attention, so his own voice is a charming curiosity, a subtle blend of the British, American and Irish influences in his life. I wonder why people so often decide that he’s an oddball? Or that he’s especially precious as an actor? He comes across as smart and engaged, unusually willing to work long and hard on a character and unusually willing in conversation to try and make sense of that work. He’s a thinker and a grafter.

Can he explain the paradox himself? Why do people prefer to see him as a lone, strange presence in cinema rather than someone who puts an extraordinary amount of work and thought into what he does? ‘Maybe people just prefer to believe the other thing,’ he reasons. ‘I honestly don’t know. I can’t really account for that. It’s an odd thing, though. It feels odd, yeah, to be so consistently misrepresented in that way and then to have to bear responsibility for the rumours that other people create about you. But anyway, there you go.’

Lincoln is out now.

Discover Time Out original video