One hundred years ago, Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959) constructed his famed Wisconsin home, Taliesin. Ten years ago, the Milwaukee Art Museum opened its Quadracci Pavilion, designed by Santiago Calatrava. In honor of both anniversaries, the MAM has mounted a new retrospective of Wright’s work that examines and celebrates his creative vision. It also aims to make the Wisconsin native relevant to contemporary audiences by contributing to “current conversations on sustainable design.”

Filled with Wright’s seductive drawings, architectural models and innovative furniture designs, the exhibition is gorgeous. For novices, it provides a good introduction to the depth and breadth of Wright’s decades-long career. For aficionados, it offers an opportunity to view 33 drawings that have never been exhibited to the public before. They demonstrate that Wright applied the same design principles to his lesser-known, small-scale residential projects as he did to famous commissions such as Fallingwater.

Brady Roberts of the MAM cocurated the exhibition with Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, a Wright expert who served as one of the architect’s apprentices and is now director of archives for the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in Scottsdale, Arizona. Roberts and Pfeiffer respond to the massive challenge of presenting Wright’s voluminous career within six galleries by organizing the exhibition into project types: commissioned houses, workplaces, affordable housing, places of worship and urban planning.

The arrangement showcases Fallingwater, Unity Temple and Taliesin next to Wright’s more obscure buildings. The never-before-seen drawings add a level of interest to what would otherwise be a fairly conventional retrospective: Nothing in Fallingwater’s wall text, for example, deviates from standard descriptions; there’s little about sustainability. Home movies from MAM’s archives capture Wright in unguarded moments, but they are not well integrated into the rest of the exhibition.

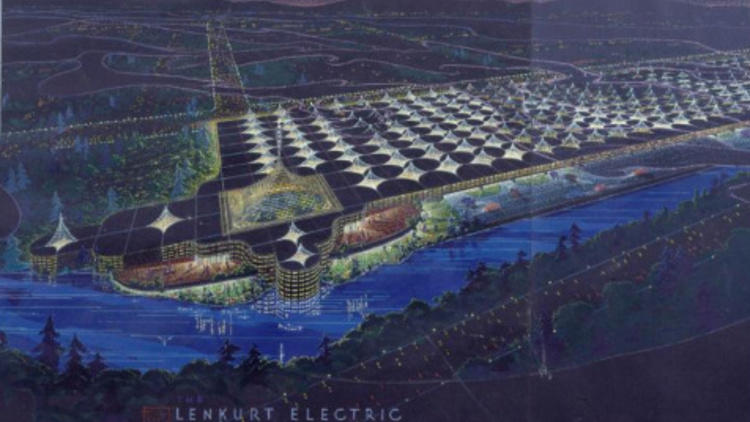

The show suggests that Wright’s concept of “organic architecture” links all of his projects, and that he treated each building as a “living entity” by responding to the specifics of its site and climate. His architecture is born of the landscape, works in harmony with the environment and immerses its occupants in nature as much as possible. Renderings for the unbuilt Raúl Bailleres House locate the main part of the house on a bluff overlooking the ocean. Wright connects it to the water through a series of terraces and water features that cascade down the hillside, and incorporates the site’s dramatic boulders into the structure of the house and outdoor spaces. More innovative still is his idea for a passive cooling system: A series of reinforced concrete chimneys or wind scoops, which echo the boulders in form, captures the prevailing ocean breezes and funnels them through the house.

But what of the 21st century and “current conversations on sustainable design”? The exhibition’s main weakness is that it fails to connect the Bailleres House (and many other projects on display) to the larger theme of Wright’s current relevance to questions about the environment. We have to analyze the Bailleres House renderings ourselves to discover how Wright proposed to integrate structure, site, climate and technology into one harmonious—and presumably sustainable—whole. Those who aren’t architects would benefit from more explicit linking of Wright’s design philosophies to today’s issues.

When I ask Pfeiffer what he hopes visitors take away from the exhibition, he replies, “The feeling that there is hope for our future. That people today can build with respect toward nature.” In our age of global warming, oil spills and other human-induced environmental catastrophes, that’s a noble—and urgent—goal. Wright’s architectural legacy suggests ways in which humans can indeed “build with respect.” The question is, will we choose to build on his pioneering efforts?