Guy Tillim began his career by photographing the effects of apartheid in South Africa. Since then, the white native of Johannesburg, now 49, has documented conflicts in Africa for wire agencies, magazines and newspapers. His images of child soldiers in the Democratic Republic of Congo or famine victims in Malawi don’t fit neatly into the disaster narratives that shape American stereotypes of the continent, however. They’re too still, too dignified or too out of context to tug at our heartstrings.

“Avenue Patrice Lumumba” (2007–08) won’t inspire donations, either. The series explores the decaying modernist architecture built by the colonial and postcolonial regimes of Angola, the DRC, Madagascar and Mozambique. Its title refers to the streets that various African cities named after the DRC’s first prime minister, who was assassinated in 1961 just weeks after his first term began. Those streets “have come to represent the loss of an African dream,” MoCP curator Karen Irvine writes in her exhibition statement.

Yet Tillim’s photos bear little resemblance to the kind of “ruin porn” that’s come to represent Detroit. The artist avoids the spectacle of great buildings gone to seed, with the exception of Beira, Mozambique’s Grande Hotel—a vast concrete structure inhabited by squatters, who hang their laundry out to dry on its curving balconies. The hotel—which has trees growing out of it—might be unrecognizable to those who opened it in 1954, hoping to attract wealthy white tourists, but it’s still bustling. Only a couple of photos, such as Park in the center of town, Gabela, Angola (2008), which depicts a desolate Toyota showroom and a playground overgrown with weeds, come off as postapocalyptic.

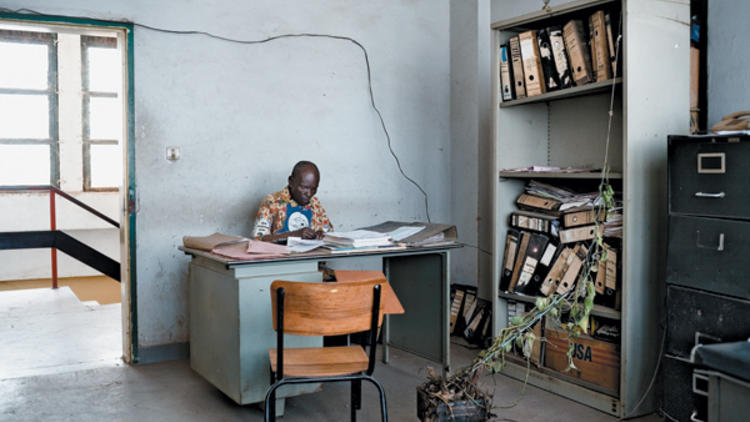

The lack of gloom in Tillim’s work stems from his ability to balance rust, trash, peeling paint and broken windows with the reality of bureaucrats, students and other citizens going about their daily lives, adapting or ignoring the buildings crumbling around them. The man working at his desk in City Hall offices, Lubumbashi, DR Congo (pictured, 2007) seems unaware, at least for the moment, that his plant is about to eat his collapsing bookcase. A lonely outdoor sculpture of Angola’s first president, Bust of Agostinho Neto, Gabela, Angola (2008), has a surreal air—perhaps because Neto’s bespectacled metal head looks too big for his shoulders—but viewers must divide their attention between Neto’s memorial and what appears to be a busy gas station behind it.

Irvine quotes Tillim’s wish that “Avenue Patrice Lumumba” not become “some sort of Havana-esque vision.” Here, the artist doesn’t entirely succeed. Almost no technology indicates that these scenes set in midcentury modernist public buildings aren’t taking place in the ’50s and ’60s. No one has a computer. The furniture could be decades-old castoffs from American offices, and yellowing binders and files fill every bookshelf. In Typists, Likasi, DR Congo (2007), a calendar advertising cell phones hangs above a woman hunched over an ancient typewriter. (Other photos reveal it’s not the only typewriter still in use.)

Tillim’s gaze can be so dispassionate that it’s unclear what his subject is, especially when people are absent. One can’t tell whether the focus of Private residence, Kolwezi, DR Congo (2007) is the barely visible house’s yard or something specific on that unkempt patch of land, and the composition is too dull for us to care. But the remarkable details in most images—tiny but telling—piece together a different picture of Africa from the one we usually see.