The aquarium decided to organize the exhibition “Jellies” partly because of the misconception that the animals, equipped with stinging cells, kill. In fact, most stings can’t hurt you. “Your skin is a pretty amazing armor,” notes Mark Schick, the Shedd’s special exhibits collection manager. Here are five more little-known facts about jellies.

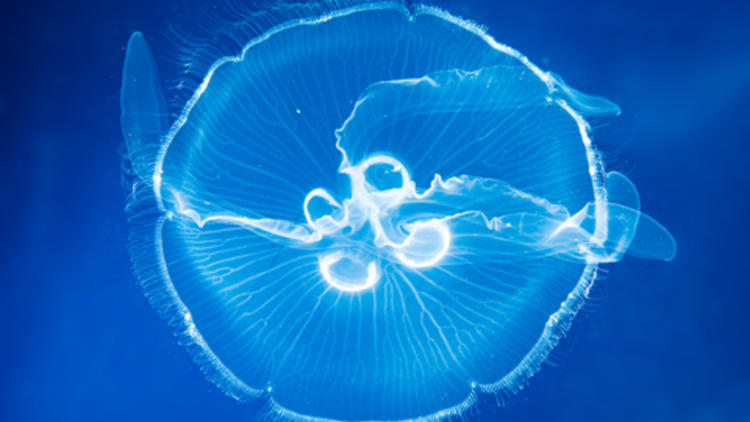

1. Jellies’ only organs: stomach, gonads and a mouth. So, eww, yes, that mouth is the in for food and the out for waste. Jellies commonly eat plankton but can also consume each other in cannibalistic fashion. Why? “They don’t have a brain, they can’t really reason it out. We think it must be a chemical cue,” Schick says.

2. It’s nearly impossible to tell males and females apart; both have gonads that look similar to the human eye. According to Schick: “When females produce eggs, there’s a slight color variation. They’re generally a bit more yellow.”

3. The Shedd used species from its own collection and flew in animals from around the world, including hairy jellies, transported in crates from Japan. The aquarium also hopes to do what few have done: Put a deadly portuguese-man-of-war on display. Because some jellies live only for a month, a few displays will feature different species throughout the exhibit's tenure. The aquarium uses iPad labels to easily switch out corresponding information.

4. Jellies reproduce in a unique fashion. “Most jellies undergo what’s called alternation of generations. What you know of as a jellyfish, that’s one of the shortest stages, that thing floating around; that’s the medusa stage," says Schick. "They are different sexes—males and females. The male will produce sperm and the female will catch it, and she’ll fertilize her eggs. The eggs will either drop to the bottom or hatch—varying on the species. And those young will swim down to the bottom. They look nothing like the jelly you or I would think of. It’s literally a tiny speck, maybe a millimeter in size, and that’s generous. That’ll go down to the bottom of the ocean and it forms a polyp—it looks like a tiny flower. Something sets it off—it goes into a process called strobilation. The free-living jellies break off, but the polyp stays there. In human terms, that baby sits at the bottom [of the ocean] and it never changes, and it can live and produce for years and years.”

5. Jellies aren't always a good thing. When enormous groupings gather, accidents have been known to take place, including clogged nuclear reactor water supplies and overturned fishing boats. The emergence of a giant group of jellies (which is, in actuality, a mass birth of jellies in the same place) can be traced to warm waters caused by climate change.

“Jellies” makes waves at the Shedd Aquarium, Friday 15–May 28, 2012. Special admission, includes regular admission: $34.95, kids $25.95. For our review of "Jellies", including more photos, click here.