When Tennessee Williams’s Camino Real opened on Broadway in 1953, the baldly poetic, loosely plotted collection of vignettes was a radical departure from the gauzy, mildly heightened realism of The Glass Menagerie and A Streetcar Named Desire. This new work trapped its mélange of characters from both literary history (Casanova, Lord Byron) and Williams’s imagination in a mysterious tropical locale from which escape seemed possible only by death—the ultimate “dead end.”

As remixed and reimagined by Catalonian director Calixto Bieito, the so-called bad boy of European theater and opera making his American directing debut, Camino Real isn’t a total dead end. But Bieito’s darkly garish semiautomatic assault can feel like a confounding cul-de-sac, sending us past one intriguing set piece after another without seeming to get us anywhere.

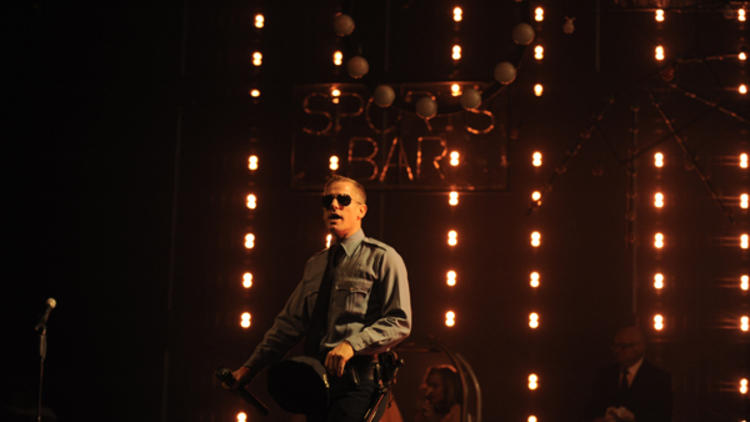

The piece is framed as the dream of a character named, appropriately enough, the Dreamer (Michael Medeiros)—Don Quixote in Williams’s original, but in Bieito and Marc Rosich’s revision, a spectacularly wasted stand-in for Williams himself who bookends the play with passages taken from the playwright’s other writings, addressed to us between swilling and hurling swigs of liquor. The suggestion, with the addition of Williams’s spoken musings on the life of the writer, is that one’s dreams and one’s demons can be one and the same.

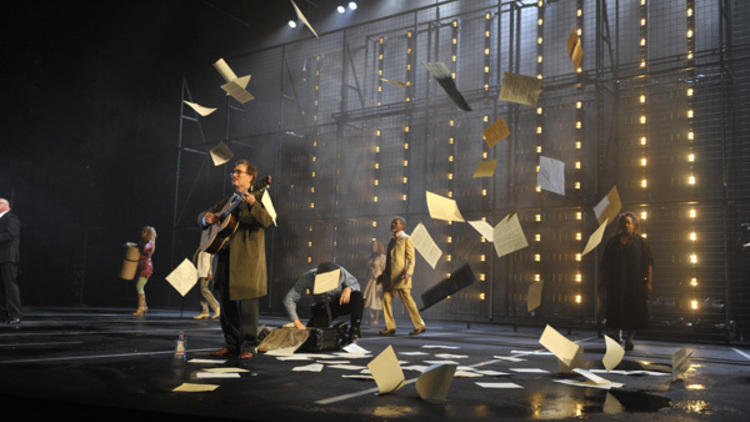

The Camino, as imagined by frequent Bieito collaborator Rebecca Ringst, is a fever dream indeed, evolving from bare stage to neon nightmare. A rifle-wielding cop (Jonno Roberts) rummages through the Dreamer’s luggage as soon as he passes out, tossing handfuls of written pages to the wind. A smarmy, suited man named Gutman (Matt DeCaro) acts as a cross between ringmaster and concierge, directing its denizens to one of two places of lodging on each side of the plaza: the exclusive Siete Mares hotel or the seedy Ritz Men Only. The plaza is patrolled by “street cleaners” (here, like the hotels, suggested but not seen) that sweep up the bodies of the dead.

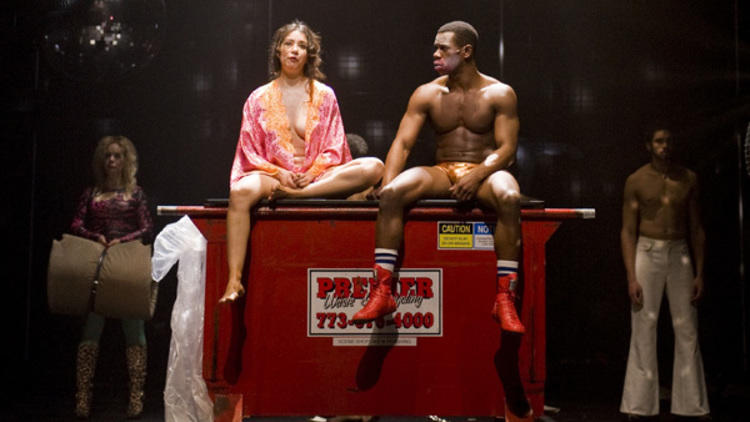

The Camino Real is infused with suggestions of sex, from eager prostitute Rosita (the always game Barbara Robertson) to aging Casanova (David Darlow) to an on-the-cruise fop (fearless André De Shields) to the Gypsy (Carolyn Ann Hoerdemann) whose for-sale daughter (Monica Lopez) is magically re-virginized every month. But the desire for sex can be as fatal as the desire for freedom, as illustrated by new arrival Kilroy (electric newcomer Antwayn Hopper), an American boxing champ with an enlarged heart “as big as a baby’s head.” Williams himself, Bieito’s vision seems to suggest, could be the one whose heart was too big for his own good, drowning himself in drink and confined with the romantics and dreamers of his own dreams—“a separate existence,” as the playwright described it.

Bieito’s mind-bending stage pictures are often thrilling, and he commands extraordinary commitment from a terrific ensemble that also includes such stalwarts as Mark L. Montgomery, Marilyn Dodds Frank and Jacqueline Williams. The overall impression is not unlike a Trap Door Theatre production with its budget increased a hundredfold.

Yet at this scale, the stuff can get in the way of Williams’s already fractured poetics. Bieito’s production is worth seeing for its stunning originality, but all the trappings start to feel like a trap of their own.