It never fails: Go to a party, talk Chicago, and someone will tell a story that begins "I swear I heard that..." or "My friend's cousin's sister told me...." Some of these tales are true, some are half-true and some are just outright blarney. For instance, did infamous baseball-toucher Steve Bartman really have to get plastic surgery to escape the wrath of angry Cubs fans? (Read on to find out.)

When such tales survive the test of time and achieve a sort of critical mass among the populace, they pass over from story into myth—and we Chicagoans love our myths. We've collected 30 of the city's most popular and subjected them to research, expert witnesses and thorough cross-examination. Impress your friends at the next party by telling them the real story.—Joel Reese

The myth: Colorful former Sox owner Bill Veeck used to drink beer out of his fake right leg, which was the result of a WWII injury.

Our verdict: False. "No, that's not true," says Mike Murphy, a host at WSCR 670-AM and self-styled Veeck historian who occasionally hung out with Veeck back in the day. Yes, Veeck liked to drink beer, and yes, he had a prosthetic leg. But the pervasive drank-beer-from-leg myth is just a melding of those two. "There wouldn't really be any room for beer, if you think about it," Murphy adds. But the Score host notes that, beyond mere ambulation, Veeck's wooden leg did serve a vice-fulfilling purpose: Veeck built an ashtray into it, complete with a metal lid.—Joel Reese

The myth: After his unfortunate star turn in the Cubs' crucial 2003 playoff loss, Steve Bartman underwent dramatic reconstructive plastic surgery and hightailed it out of the country. This one even made it into Gene Wojciechowski's best-seller Cubs Nation: "Rumor had it that immediately following the 2003 NLCS his employer, a suburban-Chicago-based consulting firm, transferred Bartman to the company's London office." The book also mentions the whispers that Bartman has "undergone cosmetic surgery."

Our verdict: False. Bartman is still in town, and he looks the same (although we hope he's ditched the turtleneck and circa-1983 earphones). "He hasn't gone under the knife, he didn't leave the country—he didn't do anything to change or alter his appearance," says sports lawyer Frank Murtha, Bartman's de facto adviser.—Joel Reese

The myth: There have been several great escapes from the Lincoln Park Zoo. Among the jailbreakers: several bears and gorillas, an elephant and a sea lion.

Our verdict: True. The last bear to escape, Mikey, climbed to freedom in 1989 over a six-foot wall using a nearby log as a boost. Duchess the elephant took off down Clark Street in 1891 while zookeepers were moving her to a summer shelter, says Mark Rosenthal, coauthor of The Ark in the Park, a history of the zoo. The pachyderm demolished a home and brewery gate and killed one horse before the posse lassoed her and tied her to a telegraph pole. In 1982, a 450-pound gorilla named Otto hopped an 11-foot partition and strolled around the zoo before being captured. And in 1989 a whole family of gorillas broke out; one of the three bit a zookeeper before being returned to captivity. As for the sea lion, in 1904 the final bells tolled for Big Ben, whose body washed ashore in Bridgman, Michigan, months after he'd made it all the way to Lake Michigan and failed to board a tug boat.—Will Clinger

The myth: In the winter of 1913, a scaly, hoofed devil baby with horns was born on Chicago's Near West Side, and was brought to social worker Jane Addams at Hull-House (800 S Halsted St between Harrison and Taylor Sts; now a museum on the University of Illinois at Chicago campus).

Our verdict: False. Though there was no devil baby, thousands of Chicagoans at the time believed there was. Addams spent 40 pages of her autobiography, The Second Twenty Years at Hull-House, trying to debunk the myth. Jane Addams Hull-House Museum director Peg Strobel says tales of demonic calamity befalling wayward men were widely embraced by immigrant women seeking to reassert the moral authority they'd lost in the New World. The alleged devil baby may have derived from one such story, and it may merely have been a child with severe birth defects. The myth also begat another: The devil baby is purported to be the source for Roman Polanski's film Rosemary's Baby, a fact that's retold ad nauseam on the city's numerous ghost tours. We could find no connection between the movie (based on New Yorker Ira Levin's best-seller) and the myth.—Martina Sheehan

The myth: Cannabis sativa (i.e., killer bud) grows in the Wrigley Field bleachers. Before the bleachers became a massive outdoor frat party, Cubs fans used to numb the pain of watching their mediocre team with a little smoky-smoke. When they were done, they threw their roaches in the bushes behind centerfield, where the seeds took root.

Our verdict: False. A drug expert insists it's entirely possible: "There's no doubt the seed can stay viable, and even last through the Chicago winter," says Allen St. Pierre, executive director of the Washington, D.C.-based National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws. "Botanically speaking, marijuana could certainly grow under such circumstances." We can't get firsthand confirmation, since the team's flaccid 2005 performance means there's no World Series being played at Wrigley Field. "We might get a few weeds out there, but no marijuana," says party-pooper Roger Baird, the head groundskeeper at Wrigley. "I'm not sure what it looks like, but from what I've seen on TV, no, there's no marijuana there." If you're looking to augment your experience in the bleachers at Wrigley, you'll have to bring your own (at your own risk, of course).—Joel Reese

The myth: The character of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer was created for an ad campaign by the Chicago-based Montgomery Ward department stores.

Our verdict: True. In 1939, Ward's copywriter Robert May whipped up a rhyming-verse story about Rudolph (originally Rollo, then Reginald) the Red-Nosed Reindeer. The story was put into a coloring book and given to 2.4 million shoppers that Christmas; 6 million were given away by 1946. By 1949, Rudolph was such a hit that May took up his bro-in-law Johnny Marks on writing lyrics and a melody to match his story. Gene Autry recorded "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer" that year and sold 2 million copies.—Lauren Viera

The myth: John Dillinger was lured to his death by a mysterious "Lady in Red."

Our verdict: False. She was wearing orange and white. Anna Sage was a Romanian brothel owner Dillinger had befriended while on the lam in Chicago in 1934. Sage was facing deportation, and, hoping to cut a deal, she tipped off the feds that Dillinger and his girlfriend, Polly Hamilton, would be accompanying her to the Biograph Theater on July 22, mentioning that she herself would be wearing a white blouse and an orange skirt. Dillinger was killed in a hail of bullets as he exited the theater. And the Lady in Orange and White? She got deported anyway.—Will Clinger

The myth: Legendary criminal John Dillinger is buried in Indiana, but his schlong rests at the Smithsonian Institute.

Our verdict: False. After he was gunned down in 1934 by G-men in front of the Biograph Theater, a morgue photo of Dillinger's corpse featured an alarming bulge under the sheet that many took to be a posthumous stiffy (it was probably his arm, in rigor mortis). This may explain the speculation about the eventual whereabouts of Dillinger's willy, but there was no mention of any penis removal in the autopsy report, and the Smithsonian denies owning any of Dillinger's parts, private or otherwise.—Will Clinger

The myth: To entertain their jailbird boyfriends at the Metropolitan Correctional Center (71 W Van Buren St at Federal St), scantily clad women have danced provocatively on the rooftop of the parking garage next door.

Our verdict: True. For years, women have indeed shaken their moneymakers to lift the spirits of their incarcerated squeezes. (They're not the only ones who've enjoyed the show: Corporate prisoners confined to cubicles in nearby office towers have also been treated to the guerrilla burlesque shows.) Sadly, the jig looks to be up: "We've taken steps to prevent that from happening in the future," relates a legal counsel employed at the triangular, Harry Weese–designed prison, a holding facility for offenders awaiting appearances in federal court. "There used to be a wire-mesh fence around that area. It's been covered with a canvas tarp, so you can't see over that side of the garage anymore." Our unnamed attorney surmises it was during visits with inmates that showtimes were scheduled, letting the boys know exactly when to sidle over to one of the narrow windows on the prison's south side for some dancing to the jailhouse rock.—Craig Keller

The myth: In the film Risky Business, the sex scene on the El was not make-believe: Tom Cruise and Rebecca DeMornay really did get all freaky.

Our verdict: False (probably). This one has been knocking around for years. This reporter was an extra on Risky Business, and this rumor was even circulating on the set back then. It's not hard to see how the story might have started; Cruise and DeMornay were an item at the time, and their chemistry on the El is palpable. But while only a select few would know for sure (it was a closed set, so only the couple themselves, director Paul Brickman, the cinematographer and a few tech hands were present), there is simply no evidence that muskrat love took place.—Will Clinger

The myth: During Prohibition, the Green Mill, then a speakeasy operated by Capone henchman Jack "Machine Gun" McGurn, would sneak in booze through a tunnel that ran from the shores of Lake Michigan to an opening behind the bar.

Our verdict: Probably false. According to current owner Dave Jemilo, there is a trapdoor behind the bar at the Green Mill that leads to a network of tunnels, and one of those tunnels does lead east toward the lake. But right after it passes under Broadway, the tunnel comes to an abrupt halt, plugged up with sand and wood planking. The likelihood that the passageway went all the way to Lake Michigan? Pretty slim, but unless you want to pull a Geraldo and bring in the dynamite, this myth will remain a mystery.—Will Clinger

The myth: The Loop's Smurfit-Stone Building (150 N Michigan Ave at Randolph St) was designed by a female architect to resemble a huge vagina in reaction to the overly phallic nature of the rest of the Chicago skyline.

Our verdict: False. Often referred to as "the Vagina Building," the Smurfit-Stone, with its diamond-shaped, sloping roof, has been featured in such films as 1987's Adventures in Babysitting because of its distinctive appearance. But the fact is, it was designed by a male architect, Sheldon Schlegman, and the architect's office assured us any resemblance to a woman's hoo-ha is purely coincidental.—Will Clinger

The myth: Hugh Hefner's original Playboy Mansion (1340 N State Pkwy between Banks and Schiller Sts; now a condo) featured revolving bookcases, hidden tunnels and a fireman's pole that dropped into an underground bar where private guests could gaze through a submerged window at bathing beauties swimming past in an indoor pool.

Our verdict: Truth runneth over like breasts in a Bunny outfit. We went straight to the source: "That's all true," says pajama man Hugh Hefner, who recently returned to Chicago to promote his new reality TV series, The Girls Next Door. "The house had no secret panels, so I added them. I'm a kid who grew up loving those Boris Karloff movies and Aladdin's Castle in Riverview [the former Northwest Side amusement park]. That's why I put suits of armor in the great ballroom and added secret panels." Bunny Kelly (Kelleigh Nelson, a resident Bunny in the '60s) says the glass-walled pool was "absolutely the greatest thing." But, she notes, "I sure as heck wouldn't skinny dip in that pool, never knowing who was in the bar." George Plimpton, in a 1999 interview for the literary journal Pagitica, recounted spending hours "waiting for the Bunnies to...plunge into the pool." All this debauchery fits with the Latin inscription on the brass plaque at the mansion's entrance, which read Si Non Oscillas, Noli Tintinnare: "If you don't swing, don't ring." —Debby Herbenick and Tim McCormick

The myth: Mass murderer Richard Speck got breast implants while in Stateville Correctional Center—on the taxpayers' dime.

Our verdict: False. This myth stems from the notorious "Secret Tapes of Richard Speck," a pornographic jailhouse video featuring Speck and his boyfriend that came to light in 1996, five years after he died of a massive heart attack. On the tape, Speck brags about his crimes, snorts cocaine and reveals some pendulous, womanly breasts that look to be the results of hormone injections. How he got his hands on the hormones is unknown, but there is no evidence that his transformation was paid for by public funds.—Will Clinger

The myth: Lincoln Park used to be a cemetery, and thousands of the bodies buried beneath its surface remain there to this day.

Our verdict: True. It's not all of Lincoln Park, but yes, the lakefront section between Wisconsin Street and North Avenue was a cemetery. When the land there was transformed into a public park in 1860, most of the bodies were moved to other nearby burial grounds. But many of the graves were unmarked, so they simply couldn't be located. In 1987, when ground was broken on the addition to the Chicago Historical Society building (at Clark St and North Ave), the construction crew made a grisly discovery: human bones. Lots of them.—Will Clinger

The myth: The basement of the University of Chicago's Regenstein Library became radioactive after U. of C. physicist Enrico Fermi created the first self-sustained nuclear chain reaction in 1942. His notes, which are stored at the library, are still radioactive.

Our verdict: False. Jim Vaughn, the library's assistant director for access and facilities, says, in an assuring tone, "I, along with all my colleagues who work here every day, are very free from this concern. We have a safety office on campus, and if this were the least bit true, they wouldn't allow the building to be occupied." He does note that some of Fermi's notes from his tenure at the school have been digitized, so if you look at them on a computer, you will be exposed to trace elements of radioactivity.—Mark Sinclair

The myth: Okay, so the Reg isn't hotter than Chernobyl. But it is sinking because the engineers who designed the building forgot to account for the tons of books that would be stored inside, right?

Our verdict: False. Vaughn, the U. of C.'s resident voice of reason, weighs in on this matter as well: "One can amusingly understand why people think this, because we add 110,000 printed books each year. Those weigh a lot. We have something like 4.5 million books in this building, and we're adding to them each year." But the weight, he promises, wasn't unexpected. "I talked to somebody on our A level, which is below ground," Vaughn says. "The windows have not sunk. He's been there for years."—Mark Sinclair

The myth: As part of the U. of C.'s infamous urban-renewal project in the late '50s, the school planned to build a moat around the campus (or at least portions of Hyde Park) to protect the students and faculty from the surrounding neighborhood.

Our verdict: False. Although there are plenty of mentions of the school trying to build a moat around the campus, including comments in April 2004 by university president Don Randel, they're metaphorical references to Hyde Park's economic isolation and urban renewal efforts on the South Side. Gary Ossewaarde, secretary and parks committee chair of the Hyde Park–Kenwood Community Conference, thinks the mix-up probably has to do with the unfinished canals on the Midway Plaisance. Frederick Law Olmsted wanted to dig a waterway connecting Washington Park with Lake Michigan, but his plan never came to fruition. "They started to dig for it in 1899," Ossewaarde says, "but they figured out the hydrology wasn't right. And there was a depression on, and they ran out of money."—Mark Sinclair

The myth: The Water Tower was the only structure left standing downtown after the Great Chicago Fire.

Our verdict: False. There were other downtown buildings that survived the fire, though it can be said that the Water Tower is the only remaining downtown landmark that survived the conflagration and still stands today. It should be noted that while the stone exterior of the Tower remained intact, the wooden interior caught fire and was gutted, cutting off the water supply and dooming much of the city.—Will Clinger

The myth: Just days before Mayor Harold Washington died of a heart attack, he dined at the Red Lion Pub (2446 N Lincoln Ave between Montana St and Fullerton Ave) in Lincoln Park, eating a prodigious meal that may well have hastened his demise.

Our verdict: True. One of the Red Lion's owners confirmed that the meal Washington was served included two steak-and-kidney pies, six Cokes and the trifle, a dessert consisting of, among other things, custard, whipped cream, shortcake, cookies and sherry. For years afterward, the Red Lion kitchen staff would ominously refer to that combination of menu items as "The Mayor Slayer."—Will Clinger

The myth: The hit musical Grease was created by a couple of Chicago guys and originally mounted at a tiny theater on Lincoln Avenue.

Our verdict: True. Jim Jacobs and Warren Casey met while acting for a local community theater; Jacobs was an office boy at the Tribune Tower, Casey a clerk for Rose Records. They eventually started writing a musical together about their high-school days. When the owner of the Kingston Mines Theater (now a blues bar at 2548 N Halsted St) overheard them performing some of the songs at a party, she offered to produce their show. It opened on February 8, 1971, for what was supposed to be a few weekend performances, but Grease was, indeed, the word. You can see a partial score and lyric sheet for the song "Foster Beach"—which would later be renamed "Summer Nights"—at the Harold Washington Library Center. —Will Clinger

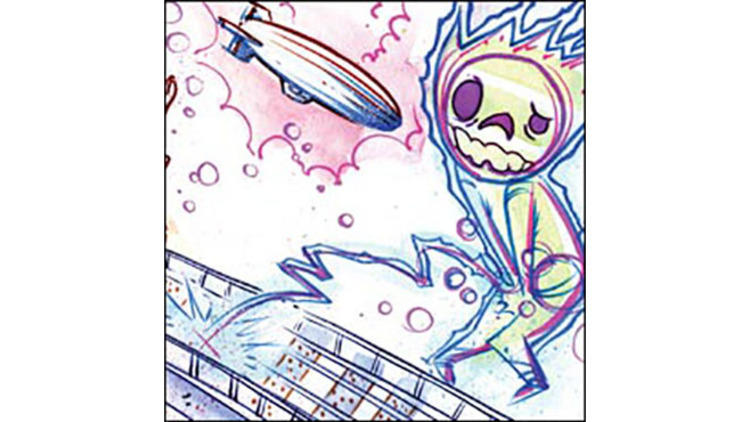

The myth: The InterContinental Chicago (505 N Michigan Ave at Illinois St) hotel used to have a dirigible docking port on its roof.

Our verdict: True. But don't try to tether your blimp at the InterContinental, because you'll wind up doing a Hindenburg. Yet when the place was built back in 1929 as the Medinah Athletic Club, there was indeed a blimp mooring next to that onion dome on the roof. Though there's a photograph of a blimp circling the building on display at the hotel, there's no evidence that a gas-filled airship ever anchored itself on the joint.—Will Clinger

The myth: The Aon Center (then the Amoco Building) at 200 East Randolph Street had its facade replaced in the early '90s because it was cracking. That's the fact. The myth is that the faulty marble cladding was chosen in the first place by the wife of Amoco's CEO.

Our verdict: False. "That is not true," says Ian R. Chin, who investigated the faulty marble in 1985 for Amoco and is now vice president and principal with Chicago structural engineering and architecture firm Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates. "The design team looked at several kinds of marble, and they selected the one that was the strongest, so I don't think the CEO's wife had anything to do with it." There's also no truth to rumors that chunks of marble fell from the building, endangering pedestrians, or that it cost more to replace the facade than it did to erect the building.—Joel Reese

The myth: You can die by electrocution if you pee off the El platform onto the third rail, which carries a whopping 600 volts.

Our verdict: True. "It's not a myth. It could happen," says CTA spokeswoman Anne McCarthy. "CTA strongly discourages urinating on the third rail—it can cost people their lives." For a little science backup, we talked to Alan Sahakian, professor in Northwestern University's department of electrical and computer engineering. He speculates if there were a perfect storm of a wet platform, perhaps a piece of tinfoil nearby and a steady stream of urine, you could get electrocuted and die. "The currents and the voltage that we're dealing with are at the levels you should respect," he says. Incidentally, there is a court case that tangentially deals with this issue: In Lee v. CTA (1977), the widow of a man who got electrocuted by standing directly on the third rail while urinating (he drunkenly wandered on to the ground-level tracks near the Brown Line Kedzie stop) sued the CTA for negligence. But this guy was standing right on the third rail. Don't do that.—Laura Baginski

The myth: Charlie Trotter makes his waiters wear two-sided tape on the bottoms of their shoes to pick up lint on the restaurant's carpeted floor.

Our verdict: False. He used to, though. In the book Lessons in Excellence from Charlie Trotter, author Paul Clarke writes that Trotter was "haunted" by lint balls that "had a life of their own, gravitating almost purposely onto the restaurant's fine dining-room carpets." Since vacuuming around the guests was out of the question, Trotter came up with the two-sided tape idea. Dining room manager Neal Wavra assured us this was no longer "our policy," but when we attempted to check one of the waiter's shoes, we were politely shown the door.—Will Clinger

The myth: The infamous "Mickey Finn" knockout drink was named after a turn-of-the-century tavern owner in the South Loop.

Our verdict: True. Before the term date-rape drug, there was the Mickey Finn—slip a guy a mickey and he'd soon be face-down in the beer nuts and ripe for the picking (of his pocket). Its namesake was the unscrupulous proprietor of the Lone Star Saloon and Palm Garden on Chicago's Whiskey Row (State Street, from Van Buren to Harrison) back in 1898. Finn created a concoction that could knock a fellow out cold, allowing Finn to stack his patsies in a back room, strip them of their valuables and dump them in an alley. When they came to, they didn't remember a thing.—Will Clinger

The myth: Liberace used his trademark candelabra for the first time at the Palmer House.

Our verdict: False. It is true that Liberace's career was launched at the Palmer House's Empire Room, a supper club from 1933 to 1976. But according to Jerry Goldberg, archivist at the Liberace Museum in Vegas, it was at the Persian Room in New York's Plaza Hotel in 1947 that he first mounted a candelabra on his grand piano. Liberace had seen the gaudy prop used in A Song to Remember, a movie about his hero, Frédérick Chopin.—Will Clinger

The myth: The Bloody Mary was invented in Chicago.

Our verdict: False. The most persistent legend about this drink holds that Fernand "Pete" Petoit invented the drink at Harry's New York Bar in Paris in the late 1920s or early '30s. A regular said it reminded him of a waitress named Mary at Chicago's Main Streets Pub—which cops nicknamed Bucket of Blood because of the frequent stabbings there—and the rest was hangover-cure history. BOB is now the Double Door (1572 N Milwaukee at Damen Ave). Double Door co-owner Sean Mulroney swears Mary was still manning the bar when he bought the place in 1992, but she's since disappeared into the annals of cocktail history.—Valerie Nahmad

The myth: A recent "trial" exonerated Mrs. O'Leary's cow from starting the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

Our verdict: True. In 1999, the John Marshall Law School held a mock trial in which attorneys and witnesses dressed up in period costumes to determine the guilt or innocence of Mrs. O'Leary and her cow. The outcome shifted the blame to O'Leary's neighbor, Daniel "Peg Leg" Sullivan, the man who had initially reported the fire. The trial was somewhat redundant, since the City Council had already passed a resolution in 1997 absolving Mrs. O'Leary and her bovine of any responsibility.—Will Clinger

The myth: Improv guru Del Close bequeathed his skull to the Goodman Theatre to be used in its next production of Hamlet.

Our verdict: True. Del had played Polonius in Goodman's last staging of the Melancholy Dane, so why not return as poor Yorick? When Goodman's executive director, Roche Schulfer, showed up at the party Close threw for himself at the hospital on the last night of his life, Close asked him if the theater had accepted the gift of the skull. Roche replied, "Yeah, but I guess I'm early." The cranium sits in the office of artistic director Bob Falls, and it has appeared in the one-man play I Am My Own Wife.—Will Clinger