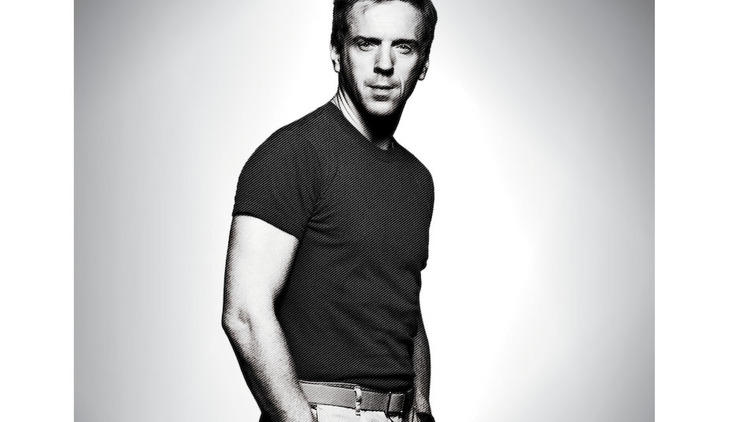

As an unknown in Hollywood, Damian Lewis took a meeting more than a decade ago with Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks. It landed him the career-boosting role of Maj. Richard Winters in HBO’s Band of Brothers. Now the 40-year-old English actor plays another American soldier, though a very different one: In Showtime’s new series Homeland, Lewis stars as Sgt. Nicholas Brody, who returns home after eight years as a prisoner of war in Iraq. But CIA agent Carrie Mathison (Claire Danes) thinks the war hero may have been recruited by Al Qaeda. Lewis spoke by phone, between getting acupuncture and flying home to his wife and two small kids in London.

You’re shooting in Charlotte, North Carolina. What do you make of the American South?

It’s charming. People are very friendly, very open, very chatty. Little bit of a reliance on fried food.

We as viewers believe your character could be a hero or a traitor. You’ve said, “I guess I’m good at playing repressed individuals…all that bubbling energy bottled up inside.” Why do you do well in this type of role?

’Cause it means I never have to make a decision. [Laughs] I can be pointedly vague about who I am. In this case, he’s been broken emotionally and physically, spiritually, psychologically, and he comes back suffering an extreme dose of post-traumatic stress disorder and carrying this great secret, which is that—well, I won’t actually reveal what it is. The series plays with the idea that maybe he’s not a force for good, that he means harm.

It’s rare for a series to suggest an American soldier’s loyalty could be questionable, that he could be turned by Al Qaeda.

It’s a contentious issue. Certainly it’s not anyone’s intention to diminish what the soldiers have done since 2001. Politically, it’s left of center, the show, it’s a liberal viewpoint about what happens when you are witness to extreme violence and you’re in a vulnerable state of mind. A prisoner of war in the Middle East would have a Koran available to him more readily than a Bible, and he seeks spiritual guidance in Allah. The series has a responsibility to denounce the idea that just because you’re a Muslim you are a terrorist. That’s part of the great ignorance of the last ten years, which has been an unhappy result of the 9/11 bombings. He finds Islam, but he may have discovered a more poetic, beautiful, honorable, generous and charitable kind of Islam, and a kind of Islam that a lot of Americans don’t believe exists.

You say left of center. That’s radical for American TV. So are the suggestions that war-hero worship can blind us to unwelcome truths, that the CIA isn’t simply good.

This series sits in the thriller genre, and the key elements for a thriller are fear, anxiety, paranoia. But on a more important political level—down here in the South, you’re surrounded by army families. A lot of these soldiers return from war traumatized. They are of course welcomed as returning heroes, as they should be, but what this show tackles is the personal cost and what it’s like for soldiers to come back to families who have moved on. A lot of these families don’t come back together because the damage is too great on both sides. So that slightly explodes the myth of a returning triumphant hero.

Especially since the hero here is seen as possibly having become “the enemy.”

Our soldiers for the last ten years have been exposed more than the rest of us to an Islamic culture. A young American soldier who has been exposed to Islamic culture for the best part of ten years is a good representation of a factional element that has decided to act against what some people see—and this is a very liberal view—as terrorist acts perpetrated by a state. This series doesn’t shy away from exploring this notion, that whilst we defend our freedoms, there is arguably no greater terror than being in a small Afghan village or in Iraq and just out of nowhere a silent drone appearing and detonating, that there are people on the other side of the world living in terror as well.

Did you speak with soldiers who’d served in the Middle East or anyone who’d been a POW?

I’ve spoken to serving soldiers. I did not manage to speak to a POW. The overwhelming sense I got from soldiers is that there’s no point trying to describe what happened because nobody here can understand. And there’s a sense of entitlement, that you’re allowed to behave how you like because of what you went through. Most shocking of all: wanting to love your children and your wife but finding that you feel numb towards them.

How are you negotiating your U.S. and U.K. lives and careers?

When I was in L.A., and I was there frequently after Band of Brothers, I was a little bit scared off [by] the corporate nature. L.A. still ranks as one of my guilty pleasures, along with butter-pecan ice cream and Coldplay albums. We always knew in my family we would go back to London. Coming here to do this show was a big, big decision. I could see what an explosive and provocative show this could be.

Homeland premieres October 2 at 9pm on Showtime.