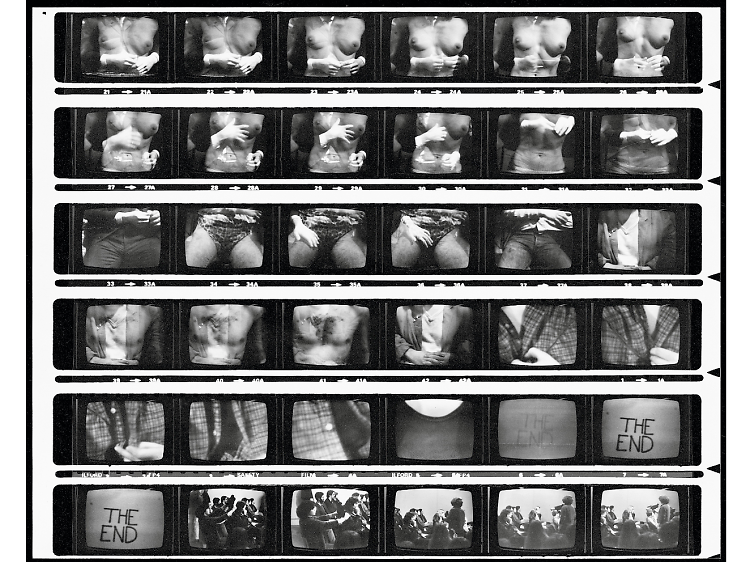

'Don't smile, you're on camera!', 1980

'For this performance, people were sitting in the audience and I would scan their bodies with a close-up video camera. I was then mixing their images with naked bodies, pretending that I could see through their clothes, like an x-ray vision. They would then see themselves on the monitor. People would sometimes say: "why are you doing this to me? Why are you invading my privacy?" It was daring. When I did it at the ICA a few people got up and left. It's very confrontational because they came to see a performance and then suddenly they are the performers.'