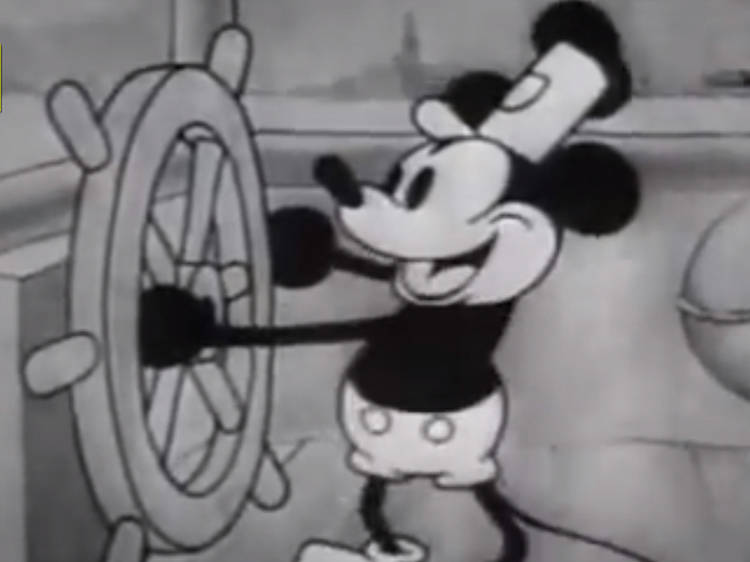

1. “Steamboat Willie” (Walt Disney, 1928)

What is it?

Before he acquired vocal cords and became the greatest cultural icon on earth, Mickey Mouse was a humble sailor who inhabited a world where everyone was unflaggingly chirpy and everything was a potential musical instrument. For want of dialogue or an engaging plot, music—whistling, drumming, mooing and a whole lot of toe-tapping—is what drives “Steamboat Willie” forward (hardly surprising, given that it was the first cartoon to use fully synchronized sound). And so the seeds for Disney’s hummable song-and-dance numbers were sown.

What’s so great about it?

Today “Steamboat Willie” appears insensitive in its depiction of animal abuse (animals are used as musical instruments). But it’s nonetheless a groundbreaking work, which set the tone for everything from “Tom and Jerry” to “The Itchy & Scratchy Show” (who repaid the debt of influence with a hilarious parody). It’s also proof that Uncle Walt was more than just the suave businessman from Saving Mr. Banks—he could actually draw, too.