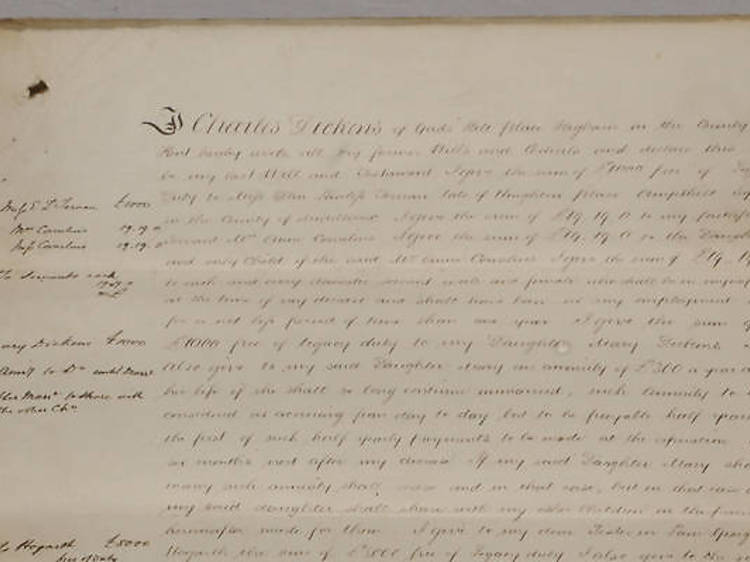

Tucked away in a quiet road behind Great Ormond Street Hospital, 48 Doughty Street was the home of a pre-fame Charles Dickens and provided the setting for many significant events in the young man’s life. In the two short years Dickens lived there, the house played host to the tragic death of his sister-in-law Mary (who was only 17) and the birth of his two eldest daughters. However, the property was also the birthplace of his first three (and possibly most loved) novels: ‘The Pickwick Papers’, ‘Oliver Twist’ and ‘Nicholas Nickleby’. The house is now the Charles Dickens Museum and has been preserved to appear as it would have done when the author was living there.