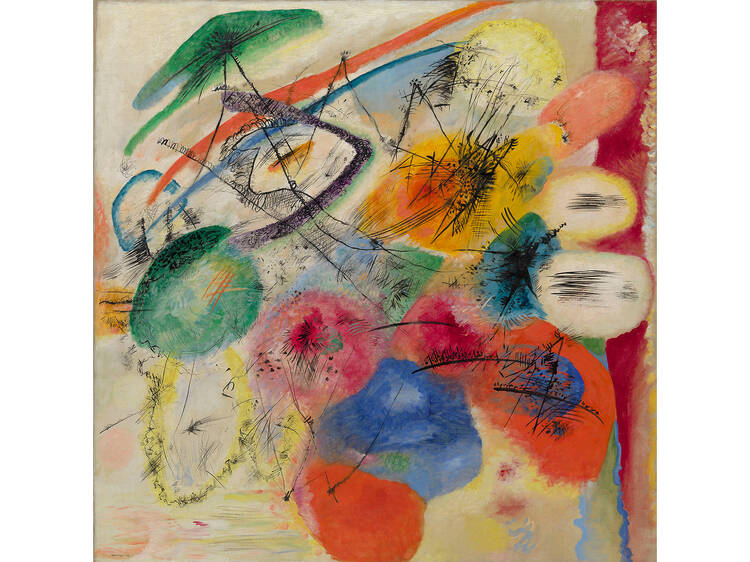

It’s been more than a century since abstraction emerged as a major (and for a while the dominant) genre in the annals of 20th century. It remains an important aspect of contemporary art, and prime examples—both historical and new—can be found in at NYC’s premier art museums, including MoMA, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Guggenheim and the Whitney. Abstraction’s roots go back to the 19th century and the emergence of art for art’s sake, a philosophy which argued for the idea that painting and sculpture should free itself from naturalism to concentrate on the substance of art itself—material, texture, composition, line, tone and color. This also meant a divorce from the centuries-long role that Western art had played in promoting the church and the state. Beginning with early proponents like James Abbot McNeil Whistler (of Whistler’s Mother fame), this focus on the intrinsic properties of art became tighter and tighter through a progression of styles from Impressionism and Post-Impressionism to Cubism and Expressionism. The final break with representation occurred during the early 1900s and teens, and various artists—Vassily Kandinsky, Kasimir Malevich—have been credited with being the first to develop pure abstraction. But regardless of who originated it, abstraction fundamentally changed the history of art, as you can see by exploring our list of the best abstract artists of all time.