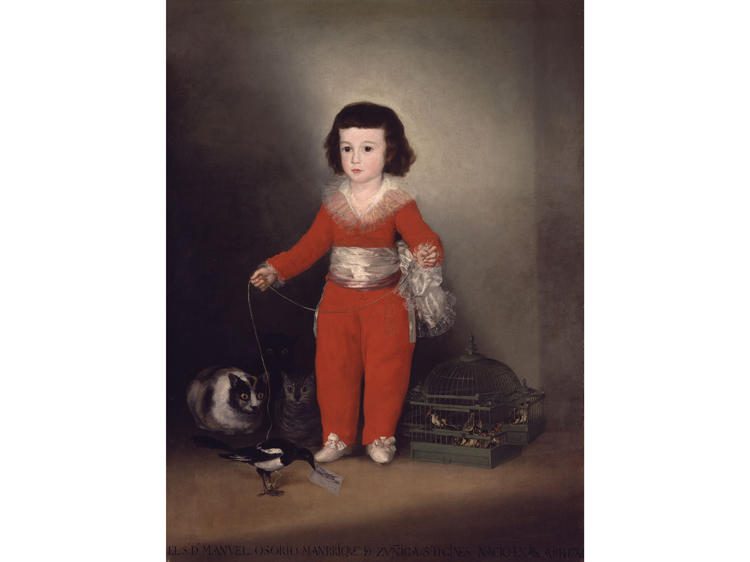

30. Woman I (1950–52), Willem de Kooning

Where can I see it?: Museum of Modern Art

Picasso’s women, Hollywood starlets and goddesses from ancient cultures have been given credit for inspiring AbEx giant Willem de Kooning’s timeless, fraught evocation of womanhood. Motherly yet monstrous, she’s prompted volumes of critical response both positive and negative. De Kooning himself struggled so much with the painting that he took it out of his studio—and only reconsidered it in light of praise by critic Meyer Schapiro.—Merrily Kerr

Photograph: Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, NY. © 2015 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York