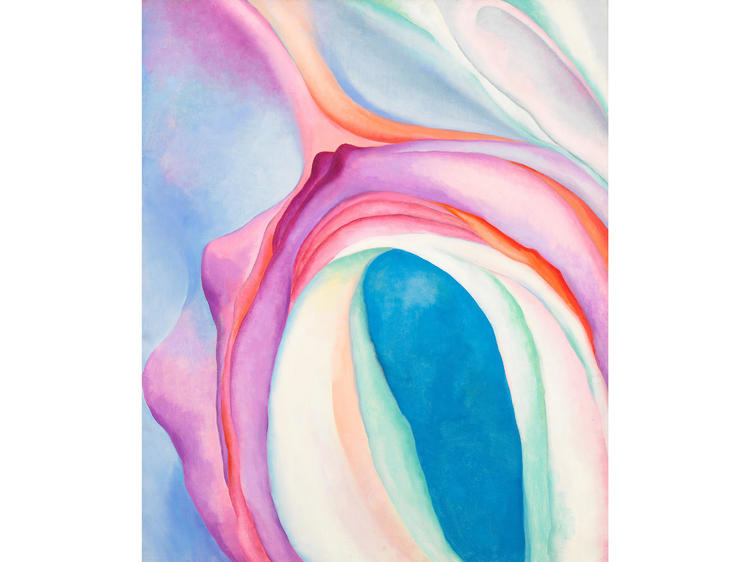

Children Meeting (1978), Elizabeth Murray

Rank: 89

In her abstract works, Murray explored the evocative power of pure color and form unencumbered by concerns about representation. And in this piece, energetic shapes and hues straight out of the visual vocabulary of comic books suggest the playful exuberance of childhood.—Heather Corcoran

Photograph: Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art; New York/The Murray-Holman Family Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS); New York