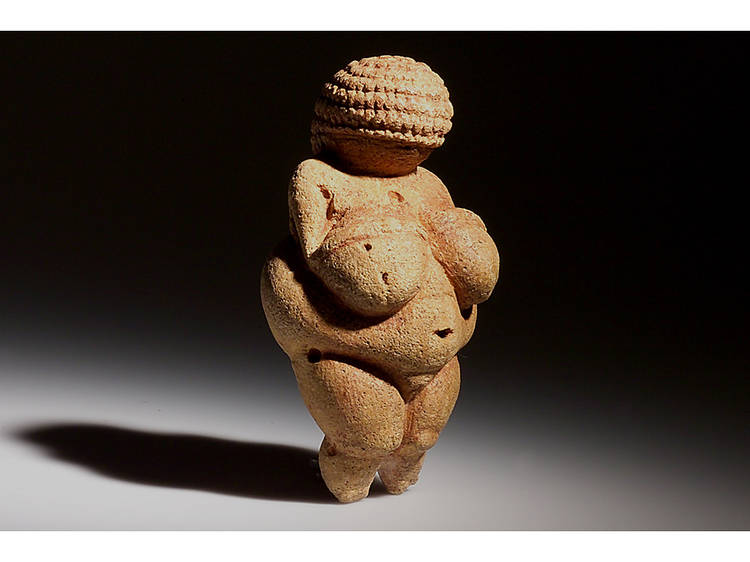

1. Venus of Willendorf, 28,000–25,000 BC

The ur sculpture of art history, this tiny figurine measuring just over four inches in height was discovered in Austria in 1908. Nobody knows what function it served, but guesswork has ranged from fertility goddess to masturbation aid. Some scholars suggest it may have been a self-portrait made by a woman. It’s the most famous of many such objects dating from the Old Stone Age.