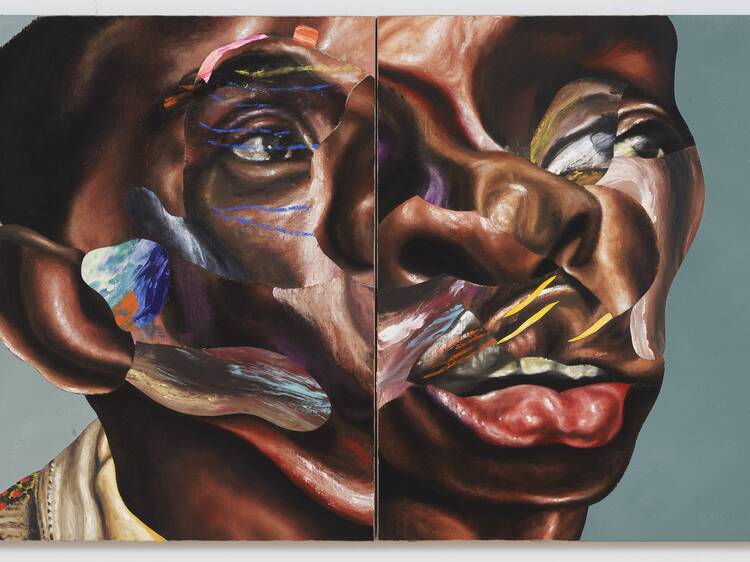

‘The Time Is Always Now’

At some point in the past, this show might have been a shock, it might have caused uproar. But this isn’t the past, this is 2024, so seeing room after room of paintings of Black figures by Black artists in the National Portrait Gallery isn’t shocking: instead, it’s just totally normal. The artists here depict the Black figure in endless ways and contexts. As straight portraits by Amy Sherald, as forgotten figures from art history by Barbara Walker, as characters of memetic mythology by Michael Armitage. The Black figure, like Blackness itself, isn't one thing, it’s complex, indefinable. The exhibition is filled with personal narratives. Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s huge, semi-collaged vision of a mother and child is beautiful and deeply intimate, Henry Taylor’s portrait of the artist Noah Davis (who died in 2015) is achingly tender and joyful, Jennifer Packer’s images of those closest to her feel too private to even look at. History rears its ugly head over and over too. It’s in Noah Davis’s vicious depiction of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre, it’s in Michael Armitage’s beautiful but frenzied scenes of social upheaval in the media age, it’s in Godfried Donkor’s gleaming image of Black heavyweight champ Bill Richmond, born into slavery but punching his way to freedom. Skin tone plays a central role in the show. Henry Taylor uses thick slabs of brown and ochre, but Toyin Ojih Odutola and Kerry James Marshall go for a deep, tenebrous onyx, and Amy Sherald paints her sitters in was