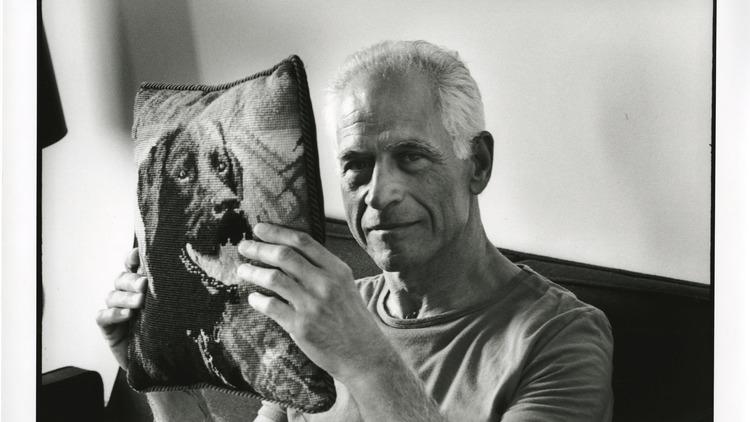

New Yorker Haim Steinbach has been lining up shop-bought and second-hand items (examples: Nike trainers, dog chews and boxes of soap powder) along with the occasional highbrow artefact on shelves since the 1970s. His is a terse kind of post-pop Proustian poetry that taps into the way objects stimulate memory and desire. His latest show, 'Once again the world is flat', is at the Serpentine Gallery.

Where does the title 'Once again the world is flat' come from?'

It's not a title, it's an object. It's a found text in its original typeset. I collect this range of statements, allegorical, idiomatic, proverbial statements, they could be headings for texts in a book or a magazine, they could be in a sentence, and then I end up selecting ones that I want to identify as art objects and that becomes a work. So it's a text on the wall. The dimensions are variable, they could be huge or very small, tiny - right by your light switch in the toilet...'

Where did you find it?

'I've had it with me for a long time, since I think the late 1980s. It deals with perception, how we perceive space. What does it mean that the world is flat, or was flat, and what does it mean that it's round? I mean, we're told it's round but we never experience it being round. We can look at the moon and say "yeah, that's a circle up there", so it raises the questions of perception, conceptualisation, identification with space, time and place...'

Is it to do with the flat surface of a shelf as well?

'Yes, you could say that. It has to do with levels and levelling. On what level are we standing? And that of course can be metaphoric too. It's about things being placed as they would be sitting on a level surface.'

‘It's like a form of dress.’

Is this show a retrospective?

'It begins with work from the early 1970s, which were paintings that evolved out of my work with the minimal paradigm and questioning how that operates. My practice really started as installation works. The shelf evolved out of that, out of a range of questions: what is a shelf, what form does it take, what does it mean that it takes different forms. And what kind of context does it establish for the object. It's like a form of dress: What are you wearing, and why are you wearing this and not that? So the work really is about installing objects and selecting arranging and presenting them. It's a presentation, not a representation. There's a big difference between the two.'

Tell us about your early paintings.

'Those paintings are like blueprints in a sense for me because they're really based on the grid structure and on selecting and arranging bars of colour. So the painting is like a game board on which the parts are moving around. The objects then in a sense replaced the bars and the so-called minimal painting, which was just a square that had one flat surface, was replaced by the shelf. It was to do with the whole contextual discourse of how you place things and the game of minimal art, which started in the 1960s and has to do with Carl Andre's floor carpet, which is made of tiles: there it is and you just say "what's that, where's the art?" You're standing on it!'

Has 'where's the art' been a response to you work?

'It's something I've experienced for years. I think it has been a big question about my work, and has been from within the art historical establishment.'

Is it to do with a perceived lack of craft?

'That's a situation with people coming into an art context who are kind of ignorant but have an opinion about art. They have designer couches and lamps and they like them because they're functional and they're visually pleasing, whatever, they like the colour. But if it's in an art gallery or a museum it must be art. The next thing that clicks is that: "Oh, it must be handmade." Well, the shelf is handmade, you can see somebody constructed it, but the objects, are they real? That has come up quite often. Really, it's quite fascinating that people project on to something what they know of it, what they have internalised, this is what makes it real.'

‘My studio doesn't end with the walls of my studio.’

Are you're saying we should look at things differently?

'I think that's what art does, or at least art that eventually becomes known, becomes historicised, because basically it's a new idea. Once you become aware of a new idea you begin to see things differently. You can't watch a movie unless you know how to read a movie. You can't appreciate Bartok until you've been exposed to music and begin to see the subtleties that make it so wonderful, you know? So, to answer your question, it is a restructuring and it raises the question of how we connect things, and what they mean.'

Do you think the connections you make are, in the end, poetic?

'Oh definitely. I've just mentioned Bartok. I mean what is he? Is he just fooling around with sounds? He's a poet, you know. That's the art ultimately. Take the pianist who has learnt to play the "Moonlight Sonata" by Beethoven. What makes a difference between somebody who plays the piano very well and somebody who becomes a lead pianist is interpretation. It's the way their fingers fall, it's timing, that's the poetry.'

Do you see your role as unleashing the poetic potential of objects?

'Yes because, just like with a poet, what makes the poem come out is a moment of inspiration. Suddenly they hear the words. Beethoven, by the time of his last compositions, was deaf. How could he hear? It's because he heard it inside and the whole structuring was totally internalised, so he knew where to go when inspiration came.'

Where do you find inspiration?

'Well, once again the world is flat. My studio doesn't end with the walls of my studio, it's the world. There's a thing in my living room that's been sitting on the floor for years and one day it becomes part of a work. I go: Wait a minute, I never thought about what this is. What is it? Why did they put the words that way on it? Who made it? What are they trying to say?'

Has the internet changed the way you work?

'It's changed it in the sense that I can look for objects on ebay. The internet is also a way to double check something, something that you came across some place else and you were considering getting and then you didn't... I think that the internet is a system that has changed people's perception of reality, of life.'

You still privilege real objects in your work, though. Do you think that will always be the case?

'We have to respond to getting a splinter in our toe. We are still here. We still need the flatness of the room, the world is flat, we are walking on flat sidewalks, streets, rooms, houses. That goes back to the shelf. The house is a shelf. The road is a shelf.'

‘All these things are poems.’

You invited people to submit objects - salt and pepper shakers - for inclusion in your Serpentine Gallery show. Why?

'When you put requests out there on that level you will get quite a number of people who will say "Gee, I want to see mine and see others." It's like seeing yourself with a group, like a group portrait, and then you say: why am I wearing this? What are they wearing? How do I look?'

People might see their cruets as art, with a value way beyond their intrinsic worth.

'Of course. Then you go back to the projection of self, and also the questioning of self. Because all these projections are ways of communication and exchange. It's a growth that bring about awareness: self awareness and the awareness of ideas and culture.'

Would you be pleased if a response to your work was for people to look more closely at their own things, their own surroundings?

'My parents had in their living room a shelving system, a room divider with objects and books on it. It was very basic, but it was a kind of display, a way of dividing the space. You can't just say that somebody chooses this or that because they need something functional. All these things are poems. All were made by people who imagined them, who had fantasies and dreams. All these things are talking to each other and anybody beginning to arranged intuitively, without being an artist or whatever, has a certain sensibility and certain feeling, as well as a lot of ideas. It's a kind of art making. And I think it is very important.'