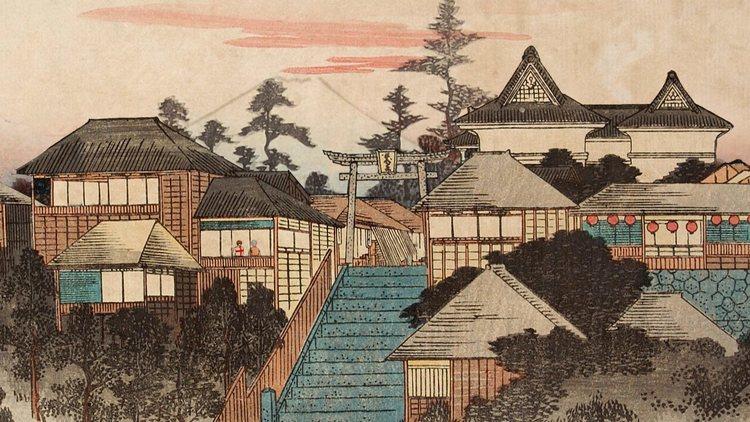

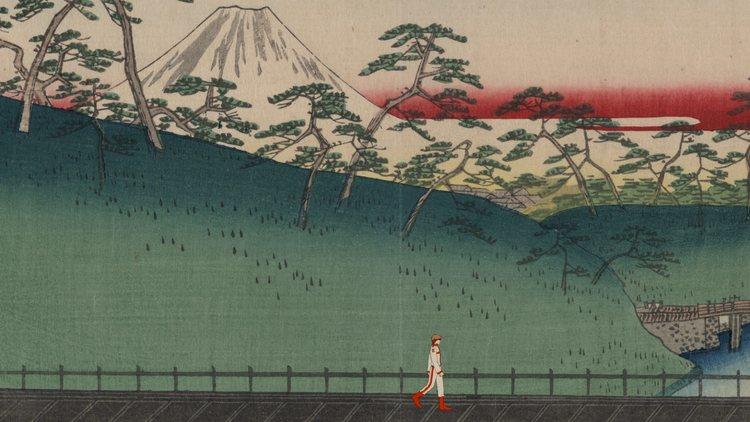

Taking over the Rose Lipman Building, a former library and community centre in Hackney, which is now an arts project space programmed by Create London, Blandy’s latest exhibition, ‘Anjin 1600: Edo Wonderpark’, focuses on the story of William Adams, the first Englishman to set foot in Japan, in 1600. In three large-scale animated cartoons that blend the styles of traditional Japanese woodcuts and contemporary manga, Adams’s journey to the Far East flows into science fiction, while Blandy’s cartoon alter ego roams alluring Oriental landscapes dressed as a space-age Knight of St George.

Visitors to this extraordinary exhibition will embark on their own quest, journeying through rooms containing sculptural installations that resemble the command centre of a space station, a traditional Zen garden and a Japanese tea pavilion, where the films will be screened. Can we all relate to William Adams?

‘Adams is an enigma. He was pretty much a voyager from another planet, coming to Japan with his alien shipbuilding technology. But I think lots of people, myself included, search for themselves out there in the world, in other cultures and other things, like books, TV and films.’

Are these films based on specific cartoons from your childhood?

‘I wanted parts of them to look like those Saturday morning cartoons I grew up watching, like "Ulysses 31" – the Japanese reimagining of Homer’s "Odyssey’", in space! My introduction to Greek myth was through this veil of cultural appropriation.’

‘Were you ever made to feel that cartoons were off-limits as art?

‘Using comics and games really grated with some of the tutors at art school. They just couldn't see the value in it. But my godfather, who's also an artist, told me when I was young: “If you want to be an artist, watch more TV.” He was half joking, but I didn’t realise that.’

Is it true that a computer game once made you cry?

‘Yes, "Final Fantasy 7". It was one of those moments when you realise you’re involved in a visceral experience. Like the first time I played "Resident Evil" and the dogs came through the window – there was genuine terror.’

Is it important to you that your work appeals to a wide audience?

'I’m interested in how creativity is displayed everyday through people's passions. I suppose I’m looking for an expanded idea of folk art that encompasses grime MCs and hardcore fighting games. Sometimes I think of my role as an artist as being like a finger, pointing at things, saying “this is interesting, this is true.” I suppose I’m lucky that I share my passions with a lot of other people.’

Did you draw the cartoon ‘you’?

‘No, I’ve often used a fictionalised "me" as a way to think about this strange idea of being an artist, but five years ago I contacted the Japanese manga artist Inko and asked her to interpret one of my films. She made a beautiful comic. I’ve worked with Inko a lot over the past five years.’

Has your cartoon appearance changed?

‘He’s a symbol of Blandy, I guess, rather than a representation. As it’s been redrawn, the image of me has become something quite separate from my appearance. Maybe I should get a haircut.’