It’s 1am and you’ve stumbled out of a pub in central London. You’re four pints in, itching for a boogie and yearning for more. So what are your options?

You could head towards one of the handful of clubs that, depending on the day of the week, might – just might – be open. You could venture to some expensive and deeply uncool corpo-lounge-club like Tiger Tiger or Piccadilly Institute. You could go to a sardine-packed, sticky-floored Irish bar like Waxy O’Connor’s or O’Neills in Chinatown. Or you could trek out for an hour or so to proper clubs with booming set-ups and trendy, exciting DJs in sort-of-suburbs like Hackney Wick, Tottenham and Canning Town.

In other words, the options for a spontaneous night out in central London – and by central we’re talking about Westminster, Kensington & Chelsea and the City – are on the whole really limited. But this hasn’t always been the case. Once upon a time, there’d have been so many late-night options that you’d have had to be incredibly determined to go home to bed at a reasonable hour. If Soho wasn’t exactly crammed with nightclubs, it still had plenty of bars open well into the early hours. Yet now, most days of the week, you’ll be left in the lurch.

It’s frustrating – and it isn’t just me that thinks so. In this recent thread of London ‘icks’, the capital’s conservative closing times popped up a lot. When did London start going to bed so early?

A doughnut-shaped cultural vacuum

The story of the UK capital’s early bedtime is primarily a tale of clubs closing and moving out to areas of the city where they’re less likely to face high rents or pressure from local authorities. Rather than clubs and bars choosing to close earlier, it’s more the case that the centre simply has so few late-night spots left – and that the number is rapidly diminishing.

According to Mike Kill, CEO of the Night Time Industries Association (NTIA), there’s a whole host of factors currently contributing to the continued demise of central London nightlife. Energy costs are high and the government isn’t doing enough to help. Customers have less disposable income during a cost-of-living crisis. And current rail strikes are worsening the deal, making it even more difficult for revellers to travel in from suburban areas.

All that stuff has created what Kill calls a ‘doughnut’, wherein the centre of town becomes something of a cultural vacuum in which only corporate, mass-appeal establishments (like Tiger Tiger and Bar Rumba) – rather than independent party spots – can survive. In other words, it isn’t just the quantity of London late-night options that is under threat, it’s the quality, too.

‘The independents are getting swallowed by corporates and we’re losing that reactive identity in British club culture,’ says Kill. ‘We’ll start to lose the identity that we are renowned for worldwide, whether we’re talking about live music or electronic music.

‘We’re not losing pinnacle venues but we are losing the periphery, where talent is able to perfect their craft. That’s the worry. That’s the big concern, particularly [with] LGBTQ+ clubs, which are hugely challenged as well.’

The independents are getting swallowed by corporates and we’re losing that reactive identity in British club culture

That leaves areas like the West End pretty much a dead zone for late-night clubbing. And while it’s certainly not the case that London as a whole shuts down about midnight, it feels like the situation is the worst it’s been in a generation. Well-established, well-curated and understandably popular clubs such as Fabric, Egg, Heaven and XOYO don’t offer much of a solution, either. When it comes to Fabric, cheap tiered tickets often sell out fast and are required to be booked well in advance – thereby killing pretty much any spontaneity. Even glammy new Tottenham Court Road club HERE closes at 2am.

Clubbers share that sentiment. Avid clubgoer Fi Gilligan, 28, says: ‘I grew up in London and I’ve never seen central London as a place to go out.’ She cites the difficulty in getting home to Hackney and the priciness of clubbing options as the main reasons for this, leading her to prefer outskirt spots in Docklands and Tottenham. Hers is a common view: there’s a reason why the likes of Hackney Wick’s garage-turned-superclub Colour Factory, Canning Town’s intimate rave spot Fold and the charmingly DIY set-up at Bermondsey’s Venue MOT are amongst the capital’s trendiest clubs right now. That’s not to mention more under-the-radar warehouse-style spots like Unit 58 in Tottenham and Low Profile Studios in Haringey, which are home to some of Gen Z’s favourite nights, like Technomate and Guttering.

‘The worst it’s been in decades’

Kill estimates that one in four clubs in London is ‘extremely vulnerable’ to closure in the near future. But it’s not just the centre of town that has fewer venues – the entire city does. Clubs have historically had a high turnover rate, but London’s new openings aren’t keeping up.

Over the past year, major venues like Oval Space, The Cause and Space 289 have all closed (with superclub Printworks about to follow suit), but very few have popped up to replace them. Last year, just 198 clubs were recorded as open in the capital – the lowest number since the mid-’90s.

And while the decline of London clubbing is very much a long-term issue – back in 2019 Dazed reckoned at least 17 significant clubs in London had closed in the 2010s, while Nesta’s clubbing map shows just how many clubs closed between 2005 and 2015 – the pandemic made things much worse. Now recession, inflation and the cost-of-living crisis have exacerbated the problem.

Plus, there are active measures in place that are making it harder to open new clubs in many parts of London. In Hackney, for example, a licensing policy announced in 2018 has imposed a curfew on all new venues of 11pm on weeknights and 12am on weekends. That year, iconic clubs The Nest, The Alibi and Visions in Dalston all closed their doors for good due to a mixture of noise complaints and rocketing rents.

I grew up in London and I’ve never seen central London as a place to go out

And that was in spite of public consultations that showed significant opposition to Special Policy Areas (SPAs) – zones in which councils impose early curfews. While venues can still apply for late licences in these areas, the existence of SPAs has made them much harder to obtain.

This all follows Sadiq Khan’s 2017 mayoral pledge to turn London into a ’24-hour city’. Yet, several years after appointing ‘Night Czar’ Amy Lamé – who, incidentally, has been given two pay rises in the past 12 months – Khan’s nocturnal ambitions don’t appear to have been realised.

Lamé and the Night Czar team said of the current state of London clubbing: ‘We know the value that clubs bring to our city and that’s why since 2016 the Mayor and I have helped to offer our support in the face of huge challenges, including rising rents, business rates, increased development and of course the impact of the pandemic.

‘Protecting and growing our capital’s unique nightlife is crucial to making London a thriving and sustainable 24-hour city, and we will continue to do all we can to offer support as we build a better and more prosperous city for all.’

Lamé points to support of venues (and prospective venues) like Sister Midnight, 100 Club and the Joiners Arms as examples of the mayor’s commitment to London nightlife. But none of those is a late-night, central London club. Community-owned live music joint Sister Midnight is in Lewisham, legendary gig venue 100 Club has an 11pm curfew and the Joiners Arms, following a funding round by community group Friends of the Joiners Arms, is set to open a new queer venue later in 2023. While it’s great that these places have gotten public support from Lamé and her office, none exactly demonstrates a dedication to genuine late-night culture in the centre of a capital city of many millions of people.

Is there any hope?

So what’s the solution, exactly? ‘A 24-hour city needs to start with 24-hour environments and that takes infrastructure,’ says Kill.

‘You’ve got to start with small pockets of infrastructure and then encourage people to come down to those pockets.’ In other words, central London clubbing has to revolve around not just licensing but resources around clubs. Public transport and food, as well as less harsh restrictions on drinking and noise, are all crucial for a 24-hour city. And, at the moment, they’re all stuff that central London is, in general, sorely lacking.

A 24-hour city needs to start with 24-hour environments and that takes infrastructure

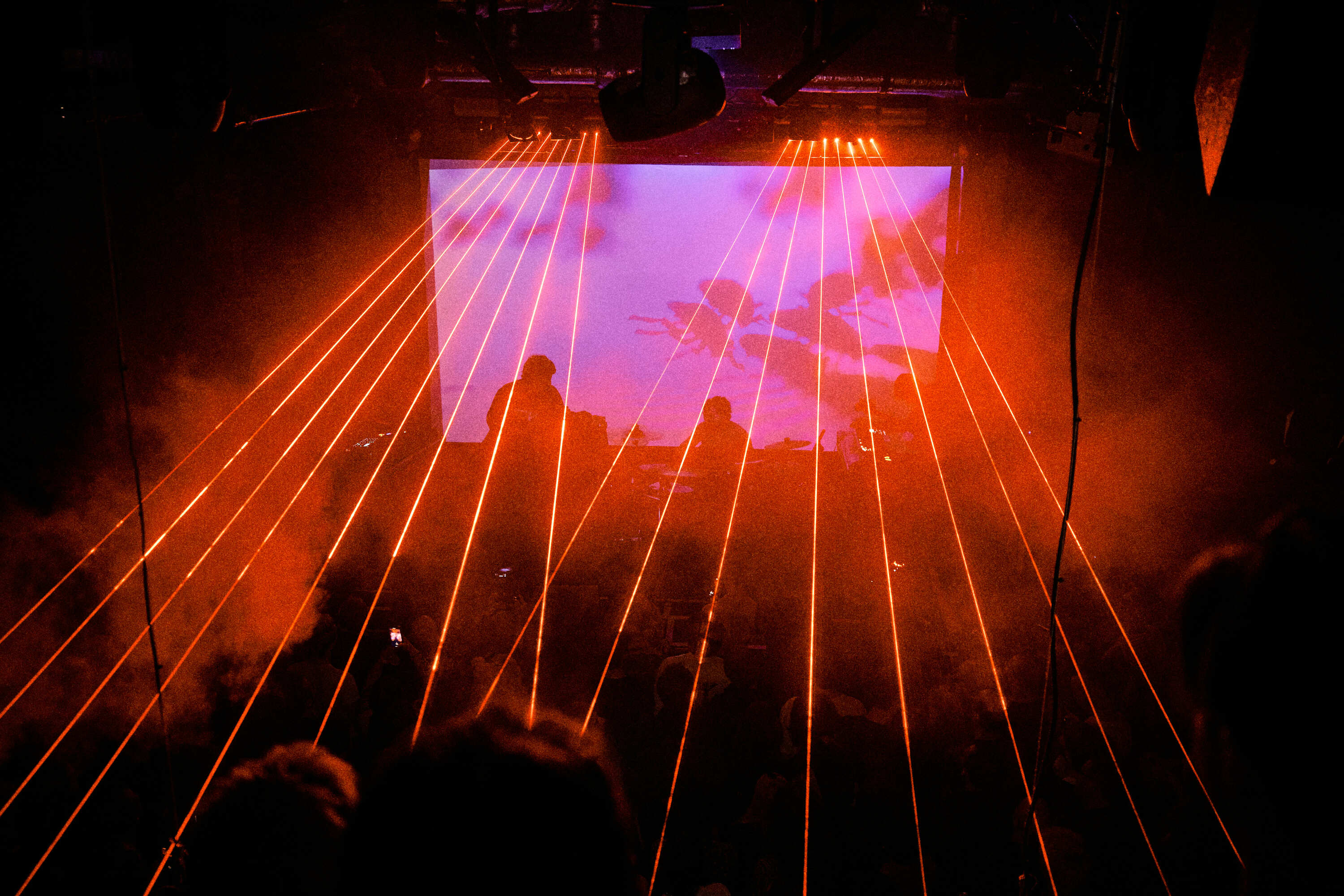

The opening of a venue like HERE seems like a step forward – but only sort of. Boasting slick audiovisual tech that shows the head-spinningly engrossing potential of the clubs of the future, DJs and electronic artists like Annie Mac, VTSS and Parris are all set to play the venue over the coming months. But as part of a billion-pound ‘immersive entertainment district’ called Outernet and funded by a multinational corporation, HERE’s day-to-day running and finances are unlikely to be quite as precarious as other independently run clubs. Plus, most of its events appear to finish reasonably early, at about 2am.

The highly anticipated opening of The Beams – a new club from the creators of Printworks – doesn’t really address central London clubbing, either. It’s out near London City Airport in Zone 3, a tidy step from the West End and the City, and it has Printworks-level pricing that is likely to make a substantial dent in most punter’s pockets. In short, it isn’t going to solve the problem of where to have a spontaneous night out in central London.

The next steps are uncertain. The NTIA has a significant report due out around March which will assess the current state of UK clubbing, while the government’s spring budget will be vital in determining how much support clubs will get in the form of alcohol taxes. The Night Czar, meanwhile, held a ‘London at Night’ conference in January and called on the government to support London’s night-time industries.

And if all this stuff comes to nothing? Well, it looks like we’ll all be trekking out to the ’burbs for a boogie for the foreseeable.

RECOMMENDED: The 31 best clubs in London right now.