Success isn’t always enough. Betty Parsons (1900-1982) was a success and a leader in her field, it just wasn't the right field. Her eponymous New York gallery was one of the most important galleries in the world. She championed Rothko and Pollock, and gave Robert Rauschenberg and Clyfford Still their first solo shows. She mattered, she changed art history. But despite all that, she still said ‘I would give up my gallery in a second if the world would accept me as an artist.’

Boohoo, poor successful, multimillionaire Betty, right? Well, the world just wasn’t a friendly place for female artists. So she made her bold, bright, colourful abstraction largely in private, largely as a hobby, always as an afterthought to her career as a gallerist.

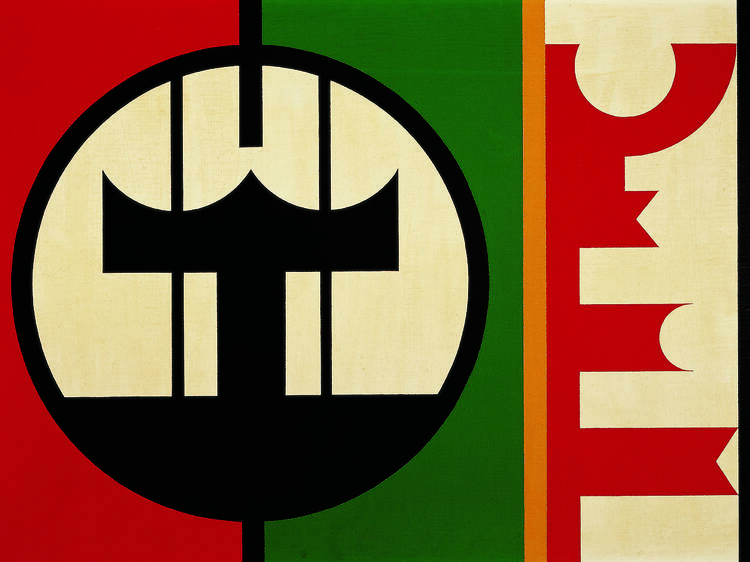

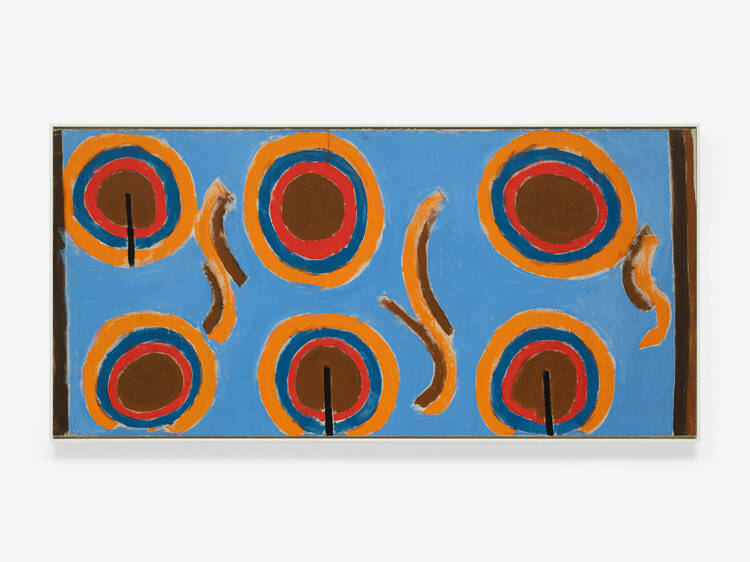

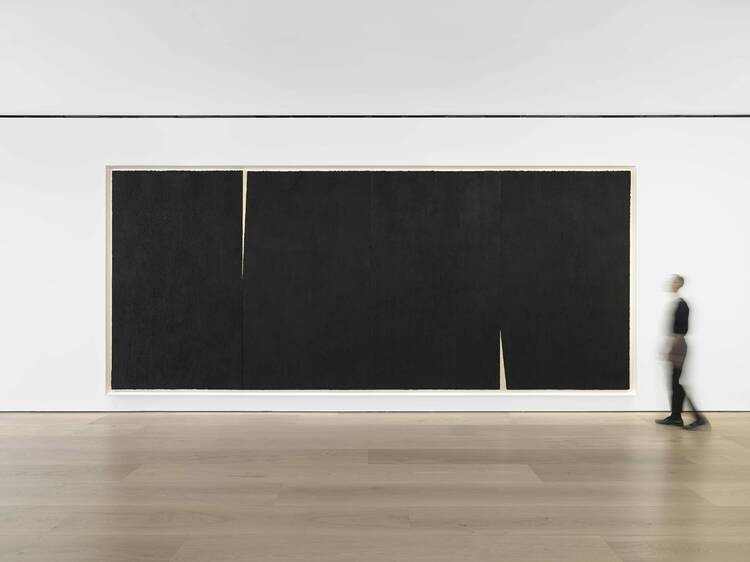

Her big acrylic paintings here are pretty unsuccessful. Rough, messy, throwaway, a bit ugly, a bit formless, a bit unfinished. The medium and size just don’t suit her; it’s like she’s constantly fighting them, and constantly losing. How does this admittedly small sample size of her career compare to the greats of her era? To Lee Krasner, Helen Frankenthaler, Clyfford Still, Willem de Kooning and so on? Not well.

Her smaller works, especially the gouaches, are way better; more accomplished, better composed, hectic, joyful. But the paintings on found wood, closer to sculptures than anything else, are great. Colourful, clever, improvised compositions that hint at forms but never go full figurative. You’d happily take a full show of them.

But t