The golden age of large-scale, site-specific outdoor New York theater was the 1990s. The tsunami of hypermonied gentrification hadn’t hit yet, so while the city was getting safer, it still seemed made of its original, if decaying, fabric. There was an abandoned elevated railway (curently the High Line) on the West Side that no one knew what to do with; there were generous donations from big philanthropies like the heroic Ford Foundation and now-departed Altria; and no one was worried about terrorism. Producer Anne Hamburger and En Garde Arts were able to stage crazy spectacles near major New York attractions.

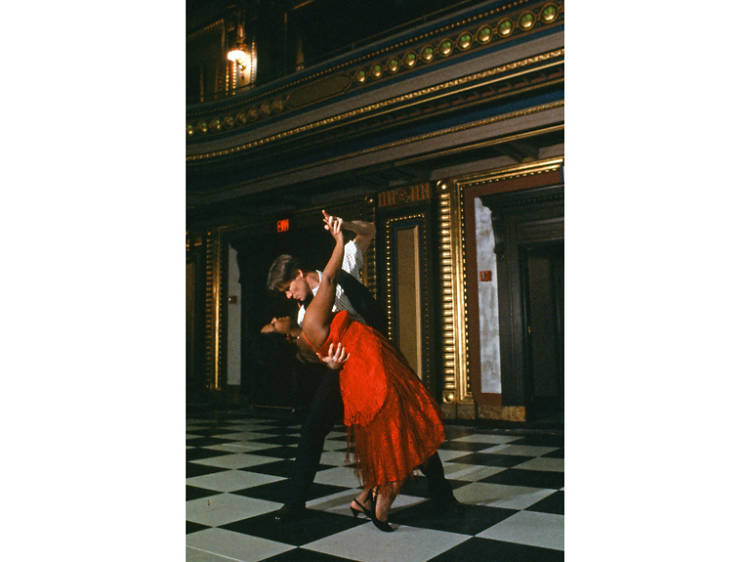

From 1985 to 1998, En Garde Arts produced 22 site-specific productions in places ranging from the Natural History Museum to an abandoned Broadway theater to a lake in Central Park to four square blocks of the Meatpacking District. The group produced major artists like Mac Wellman and Anne Bogart, won six Obies and made theater history. Now Hamburger is back in town with a new festival of emerging artists called BOSSS, or Big Outdoor Site Specific Stuff. To welcome back her city-spanning vision, we talked to Hamburger about her greatest hits. Click through to see some of the great works of that period, and be inspired to make your own.