Diane Keaton banked her Oscar and fled the Allen fold after this film. A couple more professional contributions notwithstanding, this was self-reflexively the swansong to their partnership. But if Allen lost the girl, he gained an audience – and you can’t kvetch without one. Whereas his earlier skittish missives from Napoleonic Russia (‘Love and Death’) and the twenty-second century (‘Sleeper’) won slight heed, this parochial, present-tense, blatantly personal confection seduced critics, chattering audiences, Oscar voters…

Allen’s great play was to assume his audience would (be) like him: an informed, solipsistic, nervous fantasist, only too flattered to be set up on screen. (He’d doubtless say he was making the film for himself, which amounts to the same thing.) He invites viewers to laugh with him at him: rather a subject than an object of ridicule, he lances his neuroses preemptively, controlling the exposure. It’s a limited strategy, but still glamorising in its way – if you can’t be Bogart-smooth in all things, such a fund of wisecracks is a start.

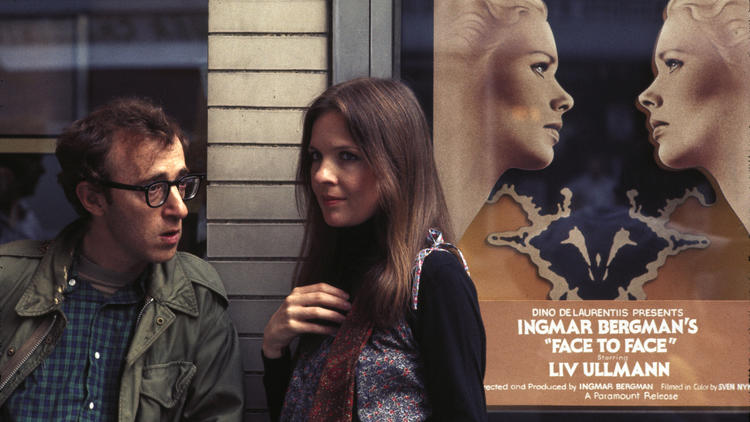

The hitch is that Allen’s comic facility disrupts his search for feeling. He begins the film in confessional mode, offering to-camera the ‘key jokes’ to his condition (he’s silenced later only by the girlfriend who doesn’t get his jokes) – but wit can be an avoidance technique, and Allen regularly cuts on a gag rather than develop a serious point. It’s not the most fluent of films anyway – a whimsical collage of childhood reminiscences and adult relationship tableaux – so while its consonance comes largely from Gordon Willis’s photography and Allen’s spacious sense of New York, pathos comes at best from Keaton’s evaporative performance and a slightly sentimental conception. The jokes, however, just keep coming.

Find out where it lands on our list of the 100 greatest movies ever made.

What to watch next:

Please Give (2010); While We’re Young (2014); When Harry Met Sally... (1989)