In Iran, a gabbeh is a colourful woollen carpet woven by the women of sheep-herding nomadic tribes. In this visually gorgeous film, Gabbeh (Djodat) is also a young woman prevented from marrying her horseman suitor by her father, who keeps coming up with lame excuses about her uncle needing to find a bride first, or his own wife having to give birth to their latest child. On one level, the film functions as fascinating ethnographic semi-documentary; on another, as a study in storytelling, both traditional and modern(-ist). Gabbeh, herself a figure depicted in a carpet, relates her tale of love and frustration to an ancient, bickering couple who may just be her future self and her lover. The tone is at once lyrical and epic, charming and whimsical.

The 50 most romantic films: numbers 30-21

30-21

Like Bob Rafelson, a director similarly obsessed with the trials and tribulations of the children of the rich, Ashby forever treads the thin line between whimsy and absurdity and 'tough' sentimentality and black comedy. Harold and Maude is the story of a rich teenager (Cort) obsessed with death - his favourite pastime is trying out different mock suicides - who is finally liberated by his (intimate) friendship with Ruth Gordon, an 80-year-old funeral freak. It is most successful when it keeps to the tone of an insane fairystory set up at the beginning of the movie.

In his second feature (following Boy Meets Girl), Carax combines his personal concerns - young love, solitude - with the stylised conventions of the vaguely futuristic romantic thriller. Loner street-punk Alex (Lavant) joins a gang of elderly Parisian hoods whose plan to steal a serum that will cure an AIDS-like disease is complicated by the deadly rival strategies of a wealthy American woman, and by Alex falling for the young mistress of a fellow gang-member (Piccoli). Again Carax's virtues are visual and atmospheric rather than narrative; while the script may occasionally smack of indulgent pretension, there is no denying the exhilarating assurance of individual sequences, and the consistency of Carax's moodily romantic vision. Certainly he would do well to create stronger female characters and avoid lines lumbered with laconic poeticism. But the film is, finally, affecting, thanks to a seemingly intuitive understanding of colour, movement and composition, and to an ability to draw from earlier films without ever seeming plagiaristic.

A minimalist monument to the rusted complacency, howling resentment, and stubborn devotion bred by a long entanglement, ‘Scenes from a Marriage’ (1973) is a virtual two-hander for the Bergman stalwarts Liv Ullmann and Erland Josephson, who reunited three decades later for what the 87-year-old director has declared his final film. Shot like its predecessor largely in merciless close-ups, the digital-video ‘Saraband’ is less a sequel than an expansive coda, beginning when Marianne (Ullmann) impulsively decides to visit her ex-husband, Johan (Josephson), after an estrangement of more than 30 years. Marianne at first appears to be our guide down a knotty memory lane, but not long after she arrives at Johan’s remote cottage, she becomes a sympathetic bystander to a newer, festering family psychodrama. Johan seethes with loathing for his doughy, hapless son, Henrik (Börje Ahlstedt), but he remains benevolent toward Henrik’s lissome kid, Karin (Julia Dufvenius). Father and daughter are penniless cellists boarding in Johan’s guest house, and the incestuous overtones of their bond, coupled with the camera’s lingering glances upon a photo of Karin’s dearly departed mother, only thicken the air of ingrown decay. Like ‘Scenes from a Marriage’, the new film is a study of diseased symbiosis that unfolds as a series of dialogues, the sparring rife with the brutal existential candour that is the lingua franca of Bergman’s cinema. ‘Saraband’ brings to mind another valedictory chamber piece –

The notoriously schmaltzy but still undeniably eye-catching film in which Aimée and Trintignant conduct an intense and often unhappy affair against an elegant, colourful background. Lelouch tricks it out with every elaborate cinematic effect he can beg, borrow or steal, ransacking both Welles and Godard for titillating devices which look good but never even begin to mesh with the subject matter (note in particular the 360 degree tracking shot at the end). In some ways the film's sheer zest and the talented cast might have won the day, were it not for Francis Lai's dreadfully corny and monotonous theme music.

This first, magnificent, outpouring of the sporadic genius of cinema’s equivalent to JD Salinger, Terrence Malick, still seems terrifically modern. That’s partly down to the career-best performances of Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek as garbage-collector Kit and naive schoolgirl Holly (who narrates), the misfit young couple who, like savage innocents, create a brief idyll and end up leaving a trail of blood through the unforgiving Montana badlands. A film of ‘visionary realism’, based on a real-life couple-on-the-run murder spree from the ’50s, ‘Badlands’ is as psychologically precise as it is splendidly visually observant. But it also exudes a timeless, mythical and tragic quality which is all the more remarkable for the languorous ease with which its story unfolds. Infused with an uncharacterisable romanticism, and employing one of the most entrancing uses of soundtrack music – from the honey voice of Nat King Cole to the jaunty yet haunting xylophone of George Aliceson Tipton – since Pasolini’s ‘Gospel According to St Matthew’, it’s a challengingly non-judgmental work which lulls the viewer into a sublime state of false security, the better to deliver a stunning but gentle essay on freedom and necessity, life and death.

Eight mismatched, unwilling Italian combatants and a donkey land on a tiny Greek island in 1941 in order to capture it for Mussolini. If the film hadn't been made by Italians, you might have thought it racist: the eight are alternately stupid, cowardly, lazy and libidinous. They scream, over-react, and fire at chickens by mistake. One night they shoot the donkey when it won't say the password. The wireless operator, whose beast it is, smashes the radio. Their battleship is blown up in the bay. No one knows where they are, and for them the war is over. Gradually, Attic transformation takes place. The hidden islanders emerge: compliant shepherdesses disrobe, the artistic lieutenant restores the frescoes in the church, breasts are bared physically and emotionally, and everyone tries Greek dancing. It isn't really together enough to be an anti-war film: there's no historical or philosophical background, no depth, nothing but sun, sand, saccharine and a stirring bouzouki score, and the surprisingly bitter epilogue doesn't begin to redress the balance.

Big-lunged lovers Allie (McAdams) and Noah (Gosling) – pampered Southern débutante and rough-earth mill worker, respectively – are on a liberty spree, and the minutes of their magical hysteria tour are duly recorded in the titular ledger-cum-framing device, in the possession of a kindly codger, Duke (Garner). He reads from the notebook to the now-elderly Allie (Rowlands), who spends her dotage befogged by an Alzheimer’s-like illness. Apparently, Allie can no longer recognise her husband or children, but has retained enough short-term memory and powers of concentration to follow Duke’s romantic narrative from day to day. Amid the sticky-sweet swamp of Jeremy Leven’s script, Rowlands and Garner emerge spotless and beatific, lending a near-miraculous credibility to their scenes together.

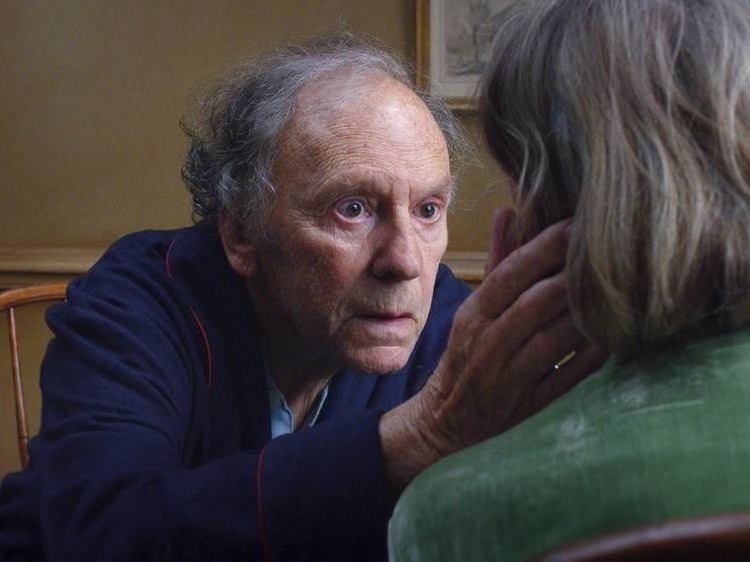

Cinema feeds on stories of love and death, but how often do filmmakers really offer new or challenging perspectives on either? Michael Haneke’s ‘Amour’ is devastatingly original and unflinching in the way it examines the effect of love on death, and vice versa. It’s a staggering, intensely moving look at old age and life’s end, which at its heart offers two performances of incredible skill and wisdom from French veteran actors Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva.The Austrian director of ‘Hidden’ and ‘The White Ribbon’ offers an intimate, brave and devastating portrait of an elderly Parisian couple, Anne (Riva) and Georges (Trintignant), facing up to a sudden turn in their lives. Haneke erects four walls to keep out the rest of the world, containing his drama almost entirely within one apartment over some weeks and months. The only place we see this couple outside their flat, right at the start, is at the theatre, framed from the stage. Haneke reverses the perspective for the rest of the film. The couple’s flat becomes a theatre for their stories: past, present and future.He asks hard questions: what do love and companionship mean when one half of a couple is facing the end? How can we cope? What’s the right way to behave? Can anyone else understand what you’re going through? Is life always worth living? What role, if any, do kindness and compassion play? And what do those words even mean in extreme circumstances?A winter light and a sense of half-dark, fading afternoon

In 1962, the French New Wave’s most avid bookworm released an adaptation of Henri-Pierre Roché’s novel ‘Jules et Jim’. It was François Truffaut’s second adaptation (and his third feature film) but this one was special: the young tyro director and the art collector from another era (Roché had died in 1959, aged 80) came together like, well, Jules and Jim. Roche’s autobiographical story of a Frenchman, Jim (Henri Serre) and a German, Jules (Oskar Werner) whose friendship survives World War I (where they fight on opposite sides, terrified that they will kill one another) and their adoration of the same impossible woman, Catherine (Jeanne Moreau) becomes, in Truffaut’s hands, a paean to passion and an ineffably elegant flick on the nose to convention. The filmmaking is wildly inventive, but not in a Godardian, clever-clogs manner. Instead, Truffaut and his cinematographer, the great Raoul Coutard, use handheld camera, freeze-frames, newsreel footage and song (Catherine’s ditty, ‘Le Tourbillon de la Vie’ [Life’s Whirlwind] became a hit) in the same way the trio of characters use races, bicycle trips or, in Catherine’s case, unpremeditated jumps into the Seine: to keep life (and cinema), crazy and beautiful at all times. Despite its name, this is Moreau’s film: gorgeous, capricious and dauntingly destructive, she makes a fabulous whirlwind. There is great sadness in ‘Jules et Jim’, what with the war, Catherine’s betrayals and the nebulous tragedy that is growing up, for those who c

Discover Time Out original video