More and more Malaysians want to read Malaysians. One can recite and regurgitate statistics all day long but look, simply, at the literary landscape of the country in recent times: A fresh crop of local independent publishers, mostly Malay, clustering to announce who they are and what they intend to publish to an appreciative audience, also mostly Malay.

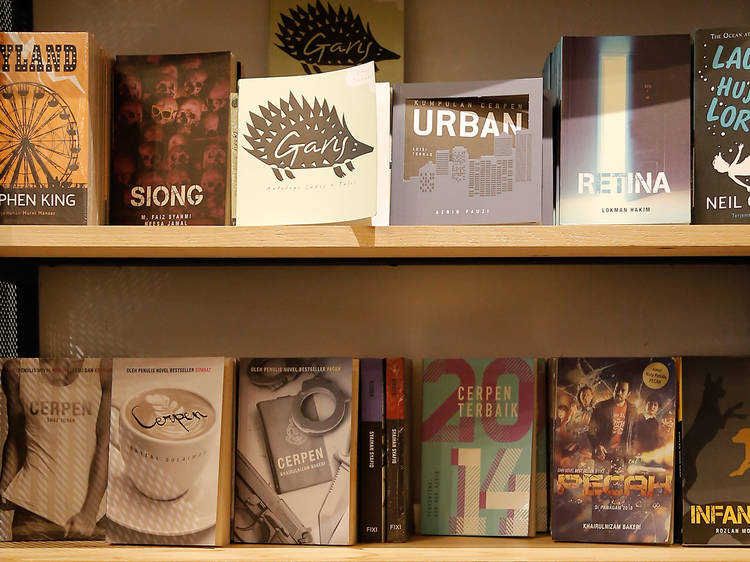

The rise of independent, small presses – devoted to pulp fiction and poetry, short stories and sociology, daring to put their heads above the parapet – are rattling the ball and chain of Malaysia’s monolithic literary mammoth: the government-funded, national institution Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (DBP), only now awakening from a long, leisurely slumber. DBP is central to the conversation; the role they play, or rather, the role they haven’t played in the betterment of the book industry has led, some would say serendipitously, to the reading renaissance of today, with cult readers and young fans praying at the publishing altars of Malay independent presses, most notably Buku Fixi, DuBook Press, Lejen Press, Rabak-Lit and Sang Freud Press. Hundreds of books have been published in the past few years collectively by these presses – some have even been adapted for the big screen – and in some cases, success has translated into brick-and-mortar storefronts.  Amir Muhammad

Amir Muhammad

Photo: Daniel Chan

The ‘indie’ Malay players

Amir Muhammad’s Buku Fixi burst into the scene in 2011, a time when nine out of ten best-selling mainstream Malay books had the words ‘cinta’, ‘kasih’ or ‘rindu’ in their title. Since its inception, the press has published over 130 titles, mostly fiction – the now-iconic, slim books announced their arrivals with loud, one-word titles: ‘Kougar’, ‘Murtad’, ‘Sumbat’, to name a few. The pulp fiction-type plot de rigueur involves crime, law and disorder, horror, serial killing, and a sprinkling of black magic: In ‘Cekik’, a 16-year-old boy living in the city with his 32-year-old girlfriend receives news of his father having been sodomised and strangled to death back in the village; meanwhile, Adib Zaini’s ‘Zombijaya’, about a zombie outbreak in KL, was adapted into ‘KL Zombi’ starring Iedil Putra and Siti Saleha.

‘In Malay commercial writing at the time, it was considered offbeat, unusual,’ says Amir. ‘It goes to show that you don’t always have to publish stories of girls wanting to be rescued by rich men, girls falling in love with their rapists. Buku Fixi is meant to be mass – we’re not radical, or whatever – but with a different flavour. If you search the words ‘Fixi’ and ‘mindfuck’ in Twitter, you’ll find teenage girls in tudung saying, “Best lah Buku Fixi ni, mindfuck betul”. Still, there are stereotypes. Someone once asked, “Why is it that in Fixi books, the women kill their rapists?” Another replied, “Because in other books, they marry their rapists”.’

That thread of thinly-veiled, cheeky humour is less thinly veiled with DuBook Press, adamantly named for its shared acronym with DBP. Mutalib Uthman’s DuBook Press is an industry heavyweight; a voice championing the comeback of Malay reading and writing in a conservative society, a voice highly critical of DBP, whom it claims on its website prefers to ‘bermesyuarat makan karipap’ and publish ‘buku-buku hidup segan mati tak mahu.’

DuBook Press, along with Buku Fixi, Clarity Publishing and Yusof Gajah Lingard Literary Agency, flew the national flag at the London Book Fair in April for the first time. The four Malaysian publishers shared a small stand which was entirely self-funded; they received no help from the public or private sector, which is not common for such a festival, as most countries’ booths are typically handled by government bodies or publishers’ associations. Buku Fixi footed half the cost for the small stand. That, including accommodations and flights, totalled up to over RM100,000.

'It goes to show that you don’t always have to publish stories of girls wanting to be rescued by rich men, girls falling in love with their rapists'

This do-it-yourself spirit embodies the entire local independent publishing industry. Writers who publish with DuBook Press, for example, are ‘encouraged to sell their own books’; that way, they take home a bigger cut of its sales. Most Malay presses, such as Hafiz Hamzah’s Obscura Malaysia, are one-man shows, often covering costs of publishing out of their own pockets. Many are friends, an ever-growing, tight-knit community trading at book fairs and events, a support system of sorts – an amalgamation of over 40 publishing houses that others have anointed with the co-opted umbrella term ‘indie’.

The word ‘indie’, though, has lost all meaning, resulting in it being rendered hollow, at least according to Hafiz: ‘Taken at face value, the term is meant to separate independent publishers from the establishment, the mainstream.’ Yet, Buku Fixi and DuBook Press, for example, are now considered almost mainstream. Too many subcultures and stereotypes have been lumped into the definition of ‘indie’: it describes everyone and no one at the same time, ascribed with connotations of bad writing, bad editing, and a promotion of ‘bad’ culture not conforming to local customs, religious and social values. Zul Fikri Zamir’s Thukul Cetak, which published former Malaysiakini chief editor Fathi Aris Omar’s book ‘Agong Tanpa Tengkolok’, was banned from entering Sabah, for instance, presumably for featuring previous Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s likeness on its cover, according to the publisher.

The slow and steady smear campaign against Malay local independent publishers is exemplified in a recent March reporting by Bernama which quoted Md Salleh Yaaper, the chairman of its board of governors, who said ‘indie’ works ‘corrupt the Malay language’, that it’s a ‘disservice to the Malays’. The same report then, of course, cited Wikipedia for its definition of ‘indie’. In early 2015, Malay Mail Online reported that the National Civics Bureau had named, in a set of slides uploaded to its website, six local independent publishers as being ‘masterminds of an anti-establishment movement’. The six named were Amir and Mutalib, along with Aisa Linglung of Lejen Press, Aloy Paradoks – real name Nurul Asyikin – of Sang Freud Press and Selut Press, Faisal Mustaffa of Merpati Jingga, and Sinaganaga, as he’s known, of Sindiket Soljah and Studio Anai-Anai.

Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka

The politicisation of language and the role of DBP

Malay literature was at its most vibrant in the ’60s, and to a certain extent, the ’70s and the ’80s, not least due to DBP. First and foremost, it’s a literary agency, a guardian entrusted with advancing, regulating and modernising the Malay language; publishing is only one part of its function, though it’s no small part. Back then, the greats of Malay literature – most notably, Usman Awang – ran the show; all the right people who were passionate about the Malay language and literature.

‘Slowly, in the ’90s, bureaucrats entered the picture,’ says Hafiz.

DBP publishes all books: dictionaries, school textbooks, general books, and even magazines and journals, such as Dewan Sastera. As the centre for national literary development, DBP sits on the giant shoulders of the government – money, then, is no issue.

'In the ’60s, the Malay scene was very open, there was a lot of political activism; you could write a story about an adulterous couple discussing the Vietnam War, that kind of thing'

‘You walk into DBP’s bookshop, your heart breaks. There’s no soul. The books are all over the place, on the floor, in disarray; and where are the good titles? The people who run the place – and there’re so many of them, too many – they’re not literary; they don’t care if books don’t sell because everything’s subsidised, isn’t it?’ Hafiz says.

Meanwhile, language is politicised – so it appears only those who are native to the Malay language are at all interested in local literature. It should flourish; not to advance a political agenda, not as some declamatory, drum-beating, great expression of national identity, but because the language possesses an innate, soft beauty. Today, DBP is no less responsible for the sentiment, sadly, that the Malay language belongs to the Malays, not Malaysians.

‘The image is that it’s a lumbering, out-of-touch institution, but they’ve published many of our writers and we’ve certainly republished some stuff that’s originally theirs. It’s not such a strict dichotomy. It’s always been used as a political plaything, I suppose. It’s state funded and it’s state dependent; that’s been the bane of DBP. In the ’60s, the Malay scene was very open, there was a lot of political activism; you could write a story about an adulterous couple discussing the Vietnam War, that kind of thing. Its heyday was probably in the ’70s – I was flipping through some older issues of Dewan Sastera and it had translations of Goethe, Hesse, discussions about Neruda,’ says Amir.

‘In any society, you need an establishment, an auntie-knows-best figure, staid and safe, but you also need an alternative to that. It’s unfair to expect DBP to do what we do, and vice versa,’ Amir says.

I Am Lejen

Photo: Daniel Chan

The argument of quality versus quantity

‘I don’t have numbers to shout of. I’m interested in ideas, the literary in literature,’ says Hafiz. His Obscura Malaysia is small but serious; he’s published less than ten titles since its inception, each one a labour of love, rooted in the belief that reading is a rich, palpable experience. In 2014, he received the author’s blessing to republish Kassim Ahmad’s ‘Dialog Dengan Sasterawan’, a collection of essays on literary criticism written between the ’50s and the ’70s before his eventual arrest under the Internal Security Act in 1976. To date, Obscura Malaysia is perhaps the only independent local press to have worked with the brilliant, formidable tag team of Eddin Khoo and Pauline Fan of Pusaka to publish ‘Obscura: Merapat Renggang’: a collection of essays, poems and short stories on arts and culture, as well as translations of great literary works such as Kafka, Homer and TS Eliot into Malay.

‘Publishing is broken. Publishing in Malaysia is too easy; everyone wants it fast. Everyone’s a publisher now. Everyone’s a writer,’ says Hafiz.

‘In the past, if a writer sends us a manuscript and if we reject it or if we tell him to rewrite it, he comes back with a better, improved manuscript. Today, he’ll simply send it to another publisher. There are so many of us now, writers don’t feel the need to improve their writing. They think to themselves, “My writing’s okay what, I got five likes on Facebook”,’ says Mutalib.

'Publishing is broken. Publishing in Malaysia is too easy; everyone wants it fast. Everyone’s a publisher now. Everyone’s a writer'

Buku Fixi receives about ten manuscripts a week. ‘Most of them follow the plots of what we’ve published before. Those are easy to reject because they’re so derivative,’ says Amir. ‘Some of it is quite crude. I tone it down, sometimes. I make sure the word ‘fuck’ doesn’t appear more than five times in a book. In our earlier books, I must admit we didn’t censor too much. I thought our readers would be older, but when I went to book festivals, I saw Form 2 kids buying our books.’

Is it a ‘reading renaissance’ if we dismiss quality for quantity, if it only means that more and more Malaysians are reading Malaysians, that we’re publishing more Malaysian books? Is it a ‘reading renaissance’ if the quality of books is, dare we say it, questionable?

A good book has good content and good writing, and above all, good editing. A good book shouldn’t suffer from substantial errors in continuity, form and style; not bizarre grammar, clichés and tropes, misplaced apostrophes. Language, however, is fluid – and therein lies the difference. Bahasa rojak, profanities and street slang, these things don’t necessarily make a bad book.

In an attempt to compete with each other, to crash books into the marketplace on hyped-up, hot taboo themes (such as sex and sexuality), presses and publishers aim now to meet immediate demand. If a book about a haunted school in KL becomes a bestseller, then the race is on to publish more stories about haunted schools in KL.

The question of quality is one that’s awkward to answer.

What is modern Malaysian literature?

Conspicuously missing from national conversation are English publishers, of which we have a few including Gerakbudaya, and Chinese and Tamil presses, of which are almost nonexistent. Raman Krishnan’s Silverfish Books is a success story, established in 1999. The independent bookstore and publisher – ‘purveyors of literature and writing par excellence’ and stocks ‘the good stuff’ – moved into a mall in Bangsar last year, a move that positions it as more mainstream, less intimidating. Silverfish Books doesn’t have a stationery section, a self-help shelf, or stacks of self-indulgent Lang Leav doodles; instead, it spotlights literature, philosophy, and above all, Malaysian English writing. Before DuBook, before Fixi, before the wave of like-minded Malay labels, there was Silverfish Books.

For all the talk of a reading renaissance in Malaysia, for all the fire-fighting and flame-throwing between the giant literary institution and the smaller guys ganging up against it, nothing much has been said about the non-Malay publishers.

‘Malay is the language of the youth. That’s the market. That’s reality,’ says Raman. ‘English is the language of the urban elite, and it was for a long time in the post-colonial period, not regarded as part of the national narrative, but it has fought its way back.’

'Literature should bind us together. Above all literature, the way food or football seemingly does in Malaysia, hailed as they are as more intrinsic to the Malaysian identity'

We must ask then, what is Malaysian literature? To add, what is modern Malaysian literature, and how do we set to task to answering that when most Malaysians aren’t acquainted even with classic Malaysian literature – when it is by nature elitist, when it isn’t affordable or accessible?

‘Look at Institut Terjemahan & Buku Malaysia’s (ITBM) translation of Faust: props to them, they try, but it’s expensive, it’s elitist. Look at their Rumi translations, look at ‘Hikayat Hang Tuah’. The classics then belong to the privileged, and yet they’re really the roots of our collective literature,’ says Mutalib.

Critics, writers and teachers, we must all be anchored on the grand canons of the classics – so in our marrow we will know what then is mediocre. Can one declare a particular work Malaysian in nature when it only addresses a certain class or community? It’s not enough to say that modern Malaysian literature is written by modern Malaysian writers – language is one thing, but the other is the psyche, the people, the culture of this country.

Literature should bind us together. Above all literature, the way food or football seemingly does in Malaysia, hailed as they are as more intrinsic to the Malaysian identity. (Malaysia’s showing at last year’s Frankfurt Book Fair was, according to Pauline Fan in her Malaysiakini article, ‘disappointing’ – with its ‘Citarasa Malaysia’ theme, cooking demos and nasi lemak samples, which no doubt were lip-smacking but surely not the stuff of literature.) Since Lat, there hasn’t been a common text that has done just that – and not to say only of the Malays, Chinese and Indians, but also the Sabahans and Sarawakians. What was it about Lat, The Kampung Boy that resonated with an entire country and beyond? We may know Hang Tuah, but can we tell his story? We know of Shakespeare, of Tolkien, sometimes even by heart, but few among us can name more than five Malaysian authors.

To the rest of the world, Malaysian literature is Tash Aw and Tan Twan Eng. With all due respect, though they have roots in Malaysia, the two write for a different audience: the Anglo-Americans. It’s not ‘by Malaysians, for Malaysians’, as people say.  Mutalib Uthman

Mutalib Uthman

Photo: Daniel Chan

The search inward for the way forward

‘We’re at a crossroads. We’re hopefully recovering from the disastrous 1990s, 2000s years – when it became very anodyne, very boring, because what was considered ‘literary’ became like a khutbah, like listening to sermons. It was a boring, barren wasteland. In those years too, there was a rising Islamic consciousness; hence everything was a romance novel with some religious flavour,’ says Amir.

Everything happens in cycles. Day turns into night, and publishing in Malaysia – and reading and writing and literature – is reviving in certain aspects, it’s all coming back around. It’s repeating, but responding to the times.

‘There needs to be a lot more bravery in writing, and a lot more bravery in reading. Readers should be more demanding, actually, of what they read. The mistake people make is in thinking and saying, “Oh, this book is good for you.” It has to stop seeming worthy. It has to be intriguing, thrilling, titillating. Nobody ever read anything because it’s “good for you”, as if reading’s the same as taking your vitamin pills,’ says Amir.

Every now and then, a Malaysian book comes along that captures for certain communities the zeitgeist of what it means to be Malaysian, of a Malaysian identity. Brian Gomez’s ‘Devil’s Place’, published in 2008 by Buku Fixi, paints a picture of a Malaysia with Malay club owners and bouncers, a Chinese taxi driver and an Indian struggling musician. It was a satirical look at the country’s then, and maybe current, socio- political state, complete with Cantonese, Hokkien and Tamil profanities, as well as jihadists and prostitutes, to up the muhibbah factor. Fifteen years prior, Rehman Rashid self-published ‘A Malaysian Journey’ in ’93, and it’s still one of the most successful books ever written of Malaysia: a passionate, rallying call for Malaysians to be Malaysians. (His second book ‘Peninsula: A Story of Malaysia’, launched in March, is repeating its predecessor’s success.)

These books underline the importance of the independents, ITBM being the exception. The organisation, managed by the Ministry of Education, began publishing original works in 2012, and is dedicated to producing and publishing local literary talents. Through its novel writing competition, for instance, it published Wan Nor Azriq’s ‘Dublin’, which is as far as it gets from Malaysia but is written in Malay and touches on topics of existentialism, as well as Jong Chian Lai’s ‘Ah Fook’, a Malay language story about a Chinese family written by a Sarawakian Chinese.

‘As a whole, I think Malaysians are comfortable not reading. It’s not intrinsic to us; we’re not inquisitive as a society. We’re easily satisfied. The idea is to encourage what and who you can with whatever audience you have,’ says Amir.

‘We need to give it a chance,’ Mutalib says. ‘Oxford Dictionary’s word of the year in 2013 was ‘selfie’, and here we say our bahasa is ‘corrupted’. Our first obligation is to encourage reading. Some say our books are too simple, but you know, people who don’t read have to start somewhere, and somewhere simple. If we give them heavy material, literary literature, tak boleh jual, kan? Mula-mula kita baca benda- benda bodoh, satu hari mesti kita nak baca benda-benda power.’

There’s talk of the second wave of Malay independent publishing, fronted by the likes of Thukul Cetak, which focuses on publishing economics, philosophy and politics, and has translated Che Guevara, Orwell and Plato.

In the near future, great books by independent publishers will climb best-seller lists (some already are at the top); reactionary gimmickry will backfire; and monolithic publishing houses stand to be the biggest losers. In the near future, publishing will separate into a two-state solution: the mainstream model, which involves the race to capture the biggest readership in as short a time span as possible; and the slow model, sustained by independent and intelligent publishers. This period of chaos, of uncertainty and upheaval, points the way forward for publishers in Malaysia who have faced decades of declining profits and readership.

‘Like everything else, in literature, first we’ll need manure, plenty of it, to grow. Then out of it trees will soar, flowers will bloom and fruits will emerge. Trash is the essential part of any evolution. Literary scenes all over the world have started with it, just like kitsch in art, or ‘muzak’ in music. We live with it, while some of us who are aware strive for something better. Quality cannot evolve in a vacuum, without quantity,’ says Raman.

Perhaps as people of oral traditions, we’re still finding our footing in the modern world of publishing. Perhaps every book published in Malaysia is a brick in the great building and rebuilding of the country. Perhaps it’s a celebration as much as it is a lamentation. It all begins with a book.

*At the time of publish, Mutalib Uthman has stepped down as CEO of DuBook Press – the company he founded seven years ago. The announcement was posted on Facebook. The publisher has not named a successor.

*At the time of publish, DBP has been contacted for comments.