‘It’s complicated’, says unflappable young Kiwi housekeeper Hallie (Tessa Bonham Jones) when her boss Roald Dahl (John Lithgow) aggressively presses her for her opinions on Israel. And it really is.

Set in Dahl’s Buckinghamshire home in 1983, the topicality of Mark Rosenblatt’s debut play is startling. Israel has invaded Lebanon, and world-renowned children’s author Dahl has written a review of a book about the war in which his condemnation of the civilian casualties inflicted by Israel has pitched into conflation of the country with Jewish people in general, accusing them of switching ‘rapidly from victims to barbarous murderers’.

As Giant begins, the review is causing an unwelcome stir ahead of the release of his new novel The Witches. An intervention of sorts is being attempted by his fiancée Felicity Crosland (Rachel Stirling, no-nonsense) and his publisher Tom Maschler (Elliot Levey, determinedly relaxed), who has roped in holidaying US employee Jessie Stone (Romola Garai, sweet but high-strung) in order to give the impression the American office considers Dahl so important they’re flying somebody out to talk to him. The plan is to persuade him to agree to a puff piece interview with the Mail on Sunday, wherein he’ll play down his remarks, thus ensuring a smooth release for The Witches.

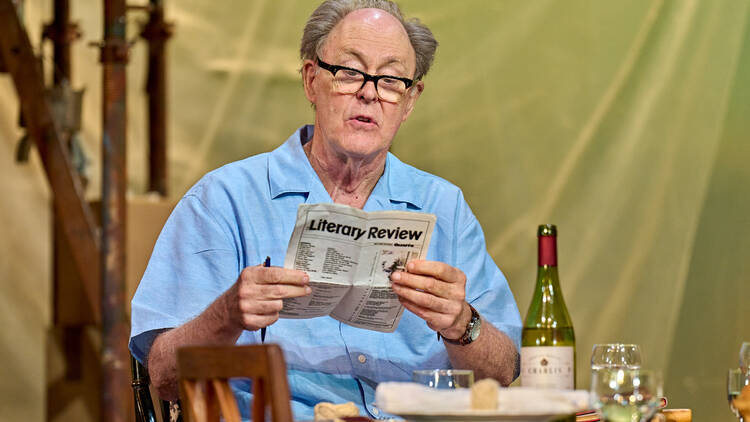

But in the extraordinary performance at the heart of Nicholas Hytner’s production, Lithgow’s slippery old Dahl is unwilling to play ball. With the crankiness that fuelled his writing turbocharged by a bad back, the noisy work on his home, and a total aversion to being told what to do, his initial response is to righteously stand by his review and explain how he’s coming from a position of sympathy for the Palestinians and Lebanese. When pressed on the worst parts of his article by Tom and Jessie (who are both Jewish) – and when Jessie dares suggest The Witches may contain antisemitic tropes – his righteousness curdles into something darker.

Giant isn’t asking if Dahl was antisemitic, because in his most famous statement on the subject, the author gave an incredibly antisemitic interview to the New Statesman in which he literally declared himself to be antisemitic.

What Rosenblatt is really asking is for us to look at what antisemitism actually is. Lithgow’s Dahl is clearly not a monster. He has a largely affable relationship with Tom, who knows how to handle him. Even as he is ever nastier to an increasingly distraught Jessie, his astute deduction that her son is brain damaged leads to an outpouring of disarming compassion from the author. He doesn’t hate them. He doesn’t necessarily even ‘mean’ much of what he says: cranky old manness and aggressive doubling down on a position everyone is telling him is wrong feel more responsible for his behaviour than deeply held beliefs. When he surreptitiously conducts the infamous Statesman interview over the phone, Rosenblatt seems to be suggesting Dahl went wilfully over the top in a gesture of petulance against his publisher and fiancée.

Rosenblatt could have written a very uncomplicated play with the evidence he had available, but has instead carefully contextualised Dahl’s words, in a way that both suggests he was not particularly ideologically committed to all this, but also shows a casual, empathy-free cruelty to Jewish people. He says vile things about them because ultimately he thinks the world has made them fair game, remorselessly lecturing Levey’s Maschler on his responsibilities as a beneficiary of the kindertransport. Maybe he meant nothing by The Witches, but his total dismissal of Jessie’s timid thoughts on the subject do not speak to a man concerned about what Jewish voices have to say to him.

It’s one heck of a debut play – well-made and sturdy, exquisitely tense, and scrupulously fair, less trying to damn Dahl than understand him. Nobody could call it a hit job, because the worst things Dahl said are all verbatim quotes. Indeed, if any of this stuff were conjecture or hearsay, it wouldn’t work. I believe this specific meeting (and Jessie) are fictional. But as an imagining of why Dahl wrote and said the things about Jews that he did in 1983, it’s meticulous, even-handed and more compassionate than angry.

It has been widely noted that Giant feels like significant programming from the new regime at the Royal Court, a theatre which has been accused at intervals over the years of programming antisemitic work. Significant in a more prosaic sense is the fact that it’s been years since a cast of anything like this stature has been persuaded to work at the Court. To a large extent that’s the Hytner effect, but it’s certainly a good omen for David Byrne’s tenure in charge.

I might in fact argue the cast didn’t really need to be this good – Dahl is the role here, with the others entertainingly drawn obstructions for him to smash into. These are small parts for Garai and Stirling, and it’s a while before Levey has much to get his teeth into. The lesser-known Bonham Jones has a tendency to upstage most of them in the more explicitly light relief part of Hallie, wandering in every now and again to say something incongruously Antipodean.

They’re first rate. But the focal point of Hytner’s naturalistic, real time production is Lithgow, and what a towering performance the American star turns in. His Dahl is magnetic: frail and malignant, cruel and kind, righteous and monstrous - if he didn’t already exist he’d have had to write himself. And the fact this largely manifests as a personality that is likeable in a grumpy sort of way means his vilest utterances hit home the more woundingly, each a kind of betrayal. It’s a magnificent performance – it’s a complicated performance.