Interview: Louis Ho

The Singapore Art Museum’s new exhibition tackles the theme of utopia. We find out more from the co-curator

A wonderful place where the sun shines, food is plentiful and everyone is always happy. Plato wrote about it in The Republic back in 380 BC, and Sir Thomas More gave it a name in 1516: utopia.

By coining the term from the Greek words for ‘no place’ and ‘good place’, More concedes that utopia does not and cannot exist. Of course, it hasn’t stopped world leaders and politicians from trying. From the kibbutz in Israel to communities in the US, history is dotted with examples of these attempts. But just how successful are they? What happens when they fail? And what, really, does utopia even mean?

This is what the latest exhibition at the Singapore Art Museum (SAM), called After Utopia, explores. The title, as co-curator Louis Ho tells us, ‘is a play on the word “after”, which can either mean what follows, or to chase what’s on the horizon’. The show tackles an ambitious and fascinating topic, but also gives the museum a chance to show off its permanent collection, some of which were recently acquired and displayed to the public for the first time.

The 20 works by artists from Asia are divided into four themes: ‘Other Edens’, which uses the garden as a symbol of paradise; ‘The City and Its Discontents’, which examines how dreams and good intentions give way to reality; ‘Legacies Left’, which looks at the legacies of various ideologies; and ‘The Way Within’, which delves into the realm of the spiritual.

One of the eye-catching pieces is Shannon Castleman’s photograph, ‘Jurong West Street 81’. No prizes for guessing where it was shot, but the artist created the image by filming residents from the opposite block (with their permission) as a way to bring back the kampong spirit. ‘She realised that even though we live in such close proximity to one another, we’re not close to the people next to us,’ Ho explains. ‘There are also dystopian connotations in the sense that it shows how we are all privy to one another’s lives, and how surveillance in the form of CCTVs is everywhere.’

On the other hand, Maryanto’s ‘Pandora’s Box’ – a site-specific charcoal and graphite drawing first conceived in 2013 and recreated on the walls of SAM – focuses on environmentalism. He is inspired by the landscape of his native Indonesia, where natural resources are often quickly stripped and the land around it turned into a wasteland. Depicting a grim, gritty, suffocating space, the piece is the very image of a dystopia.

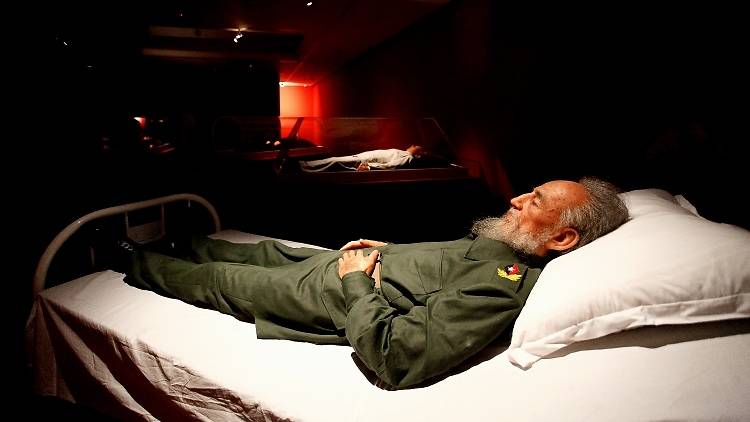

It gets even darker. One of the most unsettling pieces is Chinese artist Shen Shaomin’s installation, ‘Summit’. The work presents the life-like bodies of late communist leaders Mao Zedong, Kim Jong-il, Ho Chi Minh and Lenin encased in glass coffins, while Fidel Castro rests on his deathbed with a pump installed to make it look as though he’s breathing. ‘This work is one that I find myself thinking hard about because I’m not entirely sure I agree with the statement that Shen seems to make,’ says Ho. ‘He believes that socialism/communism is dead, but I don’t. I believe that socialism exists in balance with capitalism, as two halves of an almost necessary balance.’

Ho also declares that he doesn’t even believe in the idea of utopia – at least, not in the sense of a physical space: ‘To me, it’s more about people. You know, home is where the heart is and all that. I think it’s more about connections, and the spiritual, personal space that exists inside us.’

Regardless of your views on utopia, politics and social issues, After Utopia promises to set you thinking. Who knows – you might even find your own idea of paradise there.

Discover Time Out original video