This fall, the

Grolier Club, a private society of

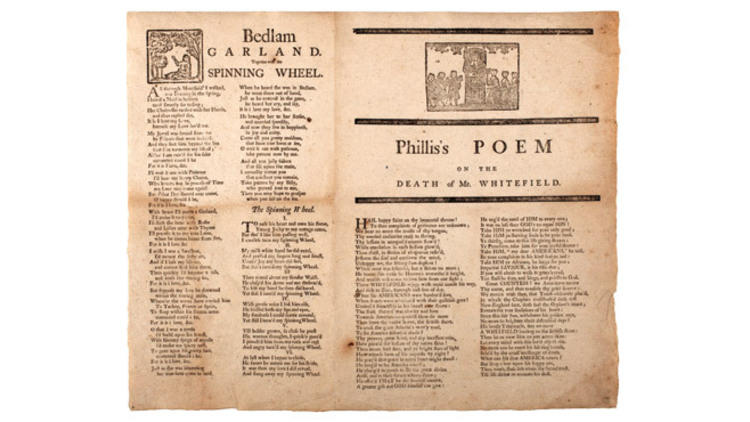

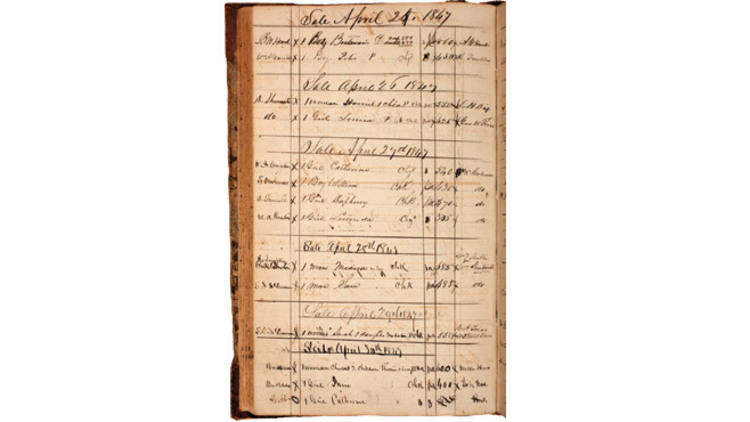

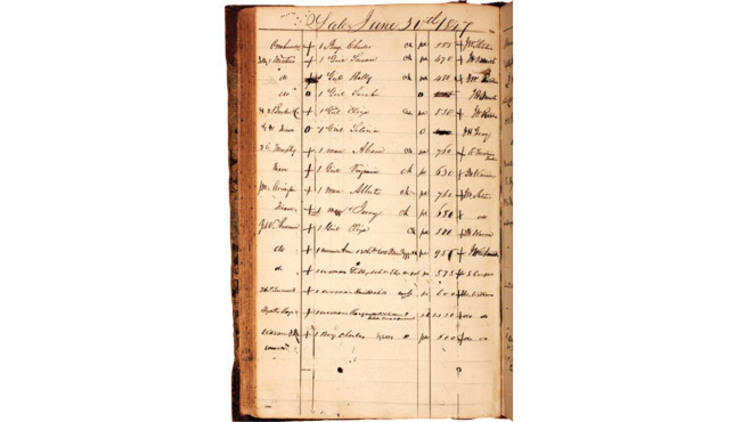

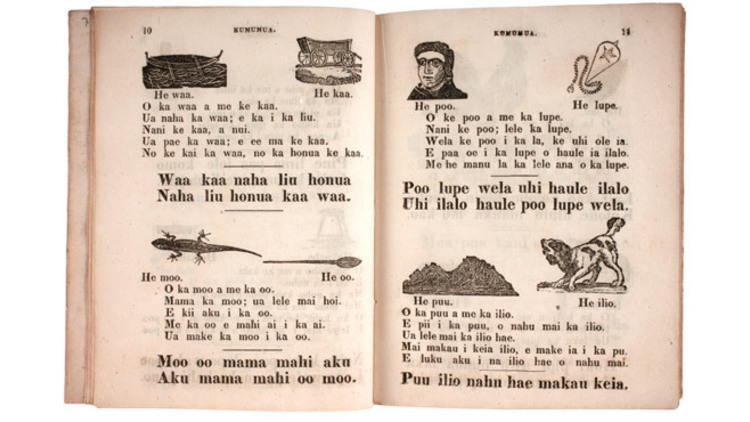

bibliophiles, celebrates the 200th anniversary of a like-minded Massachusetts-based organization with the show “In Pursuit of a Vision: Two Centuries of Collecting at the American Antiquarian Society.” Opening Wednesday 12, the exhibition includes centuries-old illustrated children’s books, nefarious ledgers and racy newspapers, all documenting pivotal moments in our country’s past. AAS curator Lauren Hewes waded through the approximately 180 artifacts that will be on display to tell us the most dynamic stories recorded on these old bits of paper.

See it now! “In Pursuit of a Vision: Two Centuries of Collecting at the American Antiquarian Society,” The Grolier Club, 47 E 60th St between Madison and Park Aves (212-838-6690, grolierclub.org). Mon–Sat 10am–5pm; free. Wed 12–Nov 17.

You might also like

NYC's best bookstores

Q&A with Copper historian

101 Things to do this fall

See more in Things to Do