[Editor’s note: This story has been extended with online bonus content.]

You joined New York City Ballet in 1987. Why have you finally decided to leave?

I had been thinking about it for a while; I just wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do. But it was coming up to another Saratoga season, and Saratoga is tough. The town has changed so drastically. It used to be this arts mecca, and now it’s suburban. It’s strip malls. And last May, Pierre Dulaine and Yvonne Marceau asked me to be a celebrity judge at their Winter Garden competition. They teach ballroom at public schools, and watching these little kids—they had such intensity and pure joy. It moved me, and I realized it’s time for me to do something else. I had heard rumors that Double Feature was coming back this year, and thought it would be a good way for me to end my tenure at the company.

Do you think that you’ll do something with kids?

I don’t know. I work a lot with the kids at the School of American Ballet, and I’m sure kids will figure into the future somehow—choreographing for them or instructing them or even having a kids’ show. But I just loved seeing that pure joy for dance. So I told Peter [Martins] that I had been thinking about this for a while. He was very polite and he said, “Okay, I understand. That’s fine.” I thanked him for giving me such a great opportunity, and he said, “Please don’t thank me—you did it all on your own.” And it’s true; I’ve always been 100 percent focused. My work ethic always came first. I always have felt that I’ve been on my own. I’ve had a lot of help. I study with Willie [Wilhelm Burmann] privately, and I do a lot of guesting; if there was an opportunity I wanted, I really went after it and made it happen. The thing about City Ballet is that you can be very busy and you can be in no-man’s-land, and I never let the no-man’s-land get me down. I always took it as a chance to do something else. I got to dance in Italy with Alessandra Ferri. I got to dance a full-length Romeo and Juliet with Oregon Ballet Theatre. I got to direct my own group and take it to Europe. I toured with Twyla Tharp for a summer. City Ballet opened so many doors.

Did you ever feel pressure to leave?

I never felt pressure. There are always new dancers coming up in the company. After Jerry [Robbins] died, there were a lot of us who had worked very closely with him and had been in those ballets for a very long time. He didn’t like to change casts. So once he died, a lot of the ballet masters were interested in trying new people out. I thought, Things are changing around here, so I should go with the flow and try to change too. I never felt that pressure like they were breathing down my back to make me leave—like, “Get out! We don’t want you anymore!” But I didn’t want to overstay my welcome, either. It’s hard to watch somebody when they’re at the top of their form and that form starts to slip. Everybody feels uncomfortable. I feel really good about where I am in my career. A couple of months ago, Christine Redpath said, “I heard you were leaving. You’re the one person who will be able to leave this place, and it will be so easy for you because you have always given 100 percent of yourself to everything you do. Your integrity is so high—you won’t have any regrets.” That was really nice. I’m like that in life, too. When I commit to something, I commit fully. I’m really there for people, which I think is a good way to live. It’s funny; I’ve never been a person who lives in the past, but ever since I said I was leaving, I’ve started to get very sentimental and reminiscent. Two Saturdays ago I was taking Willie’s class, and he had a new pianist and she was playing some beautiful Chopin music at the barre. It totally took me back to when I first started dancing in Chicago. I was seven and on top of the Ruth Page Foundation, and we would do our pliés to Chopin with the sun coming in the window. It was very idyllic. I had such a nice upbringing in the ballet world.

Did you start ballet at seven?

I started tap dancing at six. I’m a really good tapper. [Laughs]

How did you learn about dance?

My mom really wanted my sister and me out of the house, so she enrolled us in a lot of different programs: ice skating, tennis, and arts and crafts, and one day she took my sister to ballet class. I was five. I remember going to her recital and being mesmerized. I told my mom, “I want to dance on that stage, I want to do ballet,” and the teacher said, “Well, we don’t really have boys in ballet, but he can tap.” In between my tap classes, I’d watch the ballet classes and be in the dressing room doing all the steps. When I was eight, my teacher sent me into the city because they had a big production of The Nutcracker. I auditioned and was accepted and got a scholarship to study at a school in the city. That’s how I started.

Why did you take to it?

I love to move. And it’s not just ballet, but all movement.

How did you get to New York?

I was studying at the Ruth Page Foundation. When I was little, Ruth Page was still alive and for some reason she really liked me. Ruth was the funny lady who would come into ballet class and, while we’re doing pliés, would stand on her head at the barre. She was a true, original eccentric. She had her own vision and way of thinking. I always thought she was very nice and kind to me; back then, she had given me a collection of the books that she had written, and it’s just in this last year that I started looking at them and realizing how extraordinary she was. A lot of the way I look at ballet comes from her.

How? What do you love in ballet and what do you hate?

I love when people are moving and it makes sense. I hate derivative. I hate copycats. I hate people who are always trying to prove that they’re the new thing and that they’re trying to make something new—because nothing really is. But you can look at things in a different way. You can have a different perspective. I really don’t like contrived or pretentious. I love to watch dance when people are enjoying themselves, and there’s a purity about it. An integrity. I feel like what’s happening in the ballet world right now is that everybody’s copying each other and putting on layer and layer and layer of…

Crap?

Exactly. I feel we just need to go back to the basics and start over and build up from there again. We have beautiful technique and beautiful dancers. In Chicago, I was surrounded by Ruth and the teachers who used to be in her company, and they gave me a really solid training.

How old were you when you auditioned for SAB?

I was 16. I didn’t go that year, but when I was 17, I went for the summer and stayed for the year. I really knew nothing about City Ballet; the company never came to Chicago, and there wasn’t a lot on video. What we knew was American Ballet Theatre. But when I saw the company and the Balanchine work, I thought, This is so right for me. This is the kind of movement I want to do—it could be jazzy and contemporary and modern, but classical at the same time. I went to an arts high school, and in my dance-history class, when we studied Balanchine, my teacher said things like, “Oh, Balanchine is very posy, it’s angles, it’s geometry, it’s stiff.” After I moved to New York, I called her and said, “You are so wrong about Balanchine! It’s all about movement.” She was a modern dancer. The good thing is that we saw lots of Cunningham, Graham and Limón videos. It trained me to be open to more than just a secular world.

Who were your most inspiring teachers at SAB?

This was three years after Balanchine died, so I was still getting the effect of him; he was still in the air. I was so lucky to have Stanley Williams. He was an amazing teacher, and I think either you got it or you didn’t. He puzzled so many people. The thing is, he was a very quiet man and it wasn’t so much that he wasn’t saying anything, it was what he was doing with his body. His class was all about movement. Even when he said, “Hold,” you were going through the movement—it was timing and phrasing. And it was very natural for me. He would say, [Gold mimics a Danish accent.], “Of course you’re so good in my class, Tom, you are such a natural dancer so it works for you.” [Laughs]

NYCB has undergone many transitions since you first joined. How many different “companies” do you suppose you’ve been in?

I know what you mean. There’s been a lot of changeover. When I first joined, 85 percent of the people there were still Balanchine people. There was Suzanne Farrell and Patty McBride and Ib Andersen and Adam Lüders. Bart Cook. And then there was a changeover and Peter was developing his own dancers. Then there was a point when the difference was drastic. You had very young dancers between 17 and 25, and then a large group between 30 and 45. A big middle ground was missing, because a lot of them just lost interest. It wasn’t the company they wanted to be in anymore—they wanted to do other things, and it was really changing. Now it’s more consistent. There’s an evenness and a middle ground. Darci Kistler is the only Balanchine dancer left in the company. It really is Peter’s company, it’s Peter’s vision.

What is the difference?

I think with Balanchine, as everyone knows, it was about the woman. Peter started to develop the male aspect. Technique has become very emphasized, and I think that’s also an evolution of dance in general. Back in the days of Maria Tallchief, it was about personalities and charisma and the face and the essence of the dancer. Now, technique is so advanced, it’s so up front and center. That’s really the essence of what’s going on now. It’s like art: We go through classical and romantic phases. Now we’re in an extreme classical phase, and eventually we’ll go back to a romantic phase. I’m hoping. It would be nice if the two could meet. That’s the kind of dancer I love: When there is a beautiful technique, but a personality and a humanness. I love when you see the person. Technique should be there to support the dancer, but in a way it should become effortless, so that you don’t even know that it’s there.

How long have you studied with Burmann?

I’ve been with Willie for 15 years. Before Willie, a couple of us went to study with Maggie Black. People would say “black magic” and all of that. I don’t know what she was like early on, but when I went there, she worked with you. If you were a City Ballet dancer, she worked within your City Ballet parameters. She didn’t try to make you something you weren’t. She wanted to give you a beautiful line, a clean technique and make you the best dancer you could be. Wendy Whelan, Philip Neal and I were there. I only studied with her a year and a half, and then she quit and I went to Willie. He’s an amazing teacher.

How so?

His class is about movement. I always say that taking his class is like taking three. It’s so sophisticated; it’s like a Ph.D. in ballet. The way he teaches is a science and it makes sense, it all flows. And I think because he worked with Balanchine, it is natural for all of us to fall into. I just feel like—for myself, Alex Ferri, Julio Bocca and Wendy—none of us would have been able to keep dancing as long as we have without him. It makes you dance properly. If you don’t keep yourself in top form and shape, you’re much more injury prone; your body won’t hold together the same way. Any time I go on tour with my group, I take him with me. I won’t do a group without him. He’s been a big part of my dance life.

Did you talk to him about wanting to leave NYCB?

We’ve been talking for a while. When you’re a soloist, there are times when you’re really busy and times when you’re not. You’re always on call and you have to be prepared. When I would have low moments, Willie would say, “Just keep doing what you’re doing, stay in shape, it will come back.” He always was encouraging. But I’m not done. I plan on dancing more; I plan on working with him more. Our relationship in that aspect will continue.

When did you stop taking company class?

When I first got in, I would take it all the time and Stanley’s on top of that. I think after seven years. The company class is so large. I feel bad for anyone who has to teach that class. Everyone comes in in the morning; they’re tired and it can be a free-for-all. It’s a social hour. People come in and they want to catch up with their friends, and they’re not always very focused and it’s hard for the teacher to find each person in the room to give corrections. It’s very loud, and I just felt like I couldn’t concentrate anymore. I needed something more one-on-one, more personal, more direct. I needed a place where I could take my work to the next level and to keep my integrity intact. That’s when I started to explore a little bit. Maggie Black made a point of going to each person, of stopping the class to correct you. There’s something very refreshing about going back to when you were a child, when you had that attention because when you’re in a large company, it’s sink or swim. You’re thrown out there—you’re given an opportunity and you have to make something of it. Sometimes all you get is one chance. I always want to be prepared, to look my best, so for me it really made sense to study with someone like Willie. I needed some new information.

Do you think Balanchine’s classes were similar to Willie’s?

I don’t think so. From what I understand Balanchine’s class was more of his choreographic playground. Most of the dancers from that time said you had to do a class before you went into his class. I can’t even imagine that! I think one thing that Willie got was that there was always a goal and a purpose in mind. There was something specific [Balanchine] was looking for from his dancers, whether he was making a new ballet or improving technique or changing the way they looked. That’s the only thing I really wish I would have been a part of. I got so many other things. Right after my workshop, Lincoln Kirstein invited me to dinner; during the first three years of my career, once every two months I would go down to his house for dinner.

Would you describe what that was like?

I was very shy and quiet. I just observed. He was such a quick wit; so sharp and clever. You would go down to his beautiful townhouse, and you’d sit in the back living room and there was this ginormous bust of Abraham Lincoln just staring at everybody and the walls were covered with all these large Paul Cadmus drawings of Lincoln nude. It was very intimidating, and he would always position himself in his big oversized armchair; he would sit with one leg thrown over the side and talk to everybody, and it was always a different cast of characters. Lincoln would propose a question that was sort of provocative—he’d set his guests up and they would start going on and on and he would look at me and wink. He had this lovely maid, Esme, who would say, “Mr. Lincoln, dinner is ready,” and we’d go to the dining table. This is a very important thing about dining with Lincoln: He had a little bell. The first course would come, and it was always soup. He would ask a question of the table and as everyone was answering he would eat the soup really quickly and ring the bell, and before anyone got to eat the soup, it was cleared. [Laughs] I learned: Eat quickly because the food’s going to disappear. We would go to the living room and he would serve after-dinner drinks and then he would say, “Okay, it’s time to go to bed.” And you’d be like, What? He would go upstairs. We would always laugh because you’d always hear footsteps and everybody said it was the wife locked up in the attic. That house was crazy. It was an amazing old Miss Haversham house with cats and artwork.

Why did he take to you, do you think?

Well, after I performed in SAB’s [annual] Workshop Performances, the secretary called me up and said, “Lincoln really wants you to come to dinner, he was very impressed with your workshop performance.” Or he would call and say, “I saw you in Fancy Free last night; I thought you were fantastic, come down to dinner.” It was a reward, or he just liked the way I danced. I always felt touched because someone told me that when he came in toward the end, he would always ask how I was doing. I felt really lucky. I also got to work with Jerry.

You’ve danced important roles in Jerome Robbins’s ballets, including The Concert and Fancy Free. What was your relationship like with him?

I never had a social relationship with Jerry; it was just work, but I always felt like we had this bond. I don’t know if it’s because we were both Jewish? Or that he saw something in me that was very American and jazzy? I feel that a large part of why I got into the company was Jerry. On my first day, I was riding the elevator and Peter [Martins] turned to me and said, “Mr. Robbins is going to put you in his new ballet.” The next day, he started on Ives, Songs. He walked over and said, “Hi, I’m Jerry. Are you ready to work?” He started showing me steps and from that moment he just started throwing me into everything.

He made a really beautiful pas de deux for Stacy Caddell and me that was supposed to be in Ives, Songs. He cut it, but I remember in the middle of learning it, he said, “Did you ever study acting?” And I said, “I took acting classes in high school,” and the next day I was called to The Concert. One day, when I was rehearsing, he asked, “Are you flexible?” And the next day I was cast in Fancy Free. I don’t remember him ever being like, “Think about this” or, “Do this.” There was a trust he had in me.

That’s amazing.

I have such great memories of him. I don’t know if he did this for everybody, but I would perform something and he would come up to the dressing room to say, “I’m proud of you. You did a great job.” One time I was walking to the theater, and the night before I had done Port et une Soupir; he was coming out and he stopped me, threw his arms around me and gave me a big hug. He said, “I am extremely proud of you—you looked so good onstage, and it means a lot.” I never saw him outside of the theater. I was never one of those people invited to dinners. We didn’t have that kind of interaction, but there was something he saw because Robbie La Fosse, Damian Woetzel and me were the only ones who did Fancy Free for 15 years. He wouldn’t let anyone else do it.

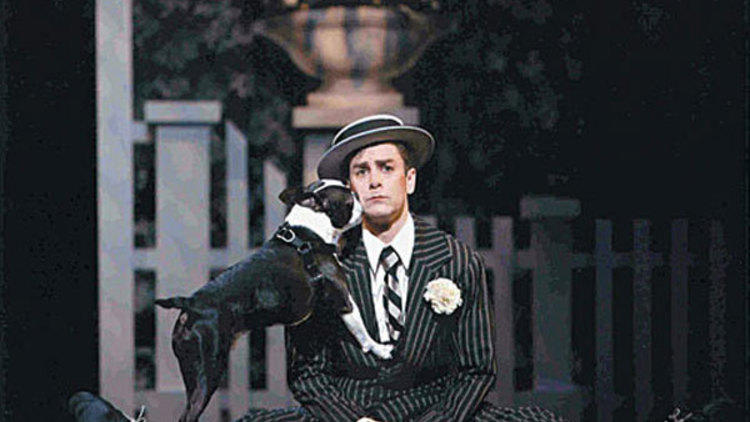

Susan Stroman created the role of Jimmie Shannon for you in Makin’ Whoopee!, the second half of Double Feature. How did you find working with her?

She was someone who really understood me as a dancer in all of my diversity. She knew I could be humorous and lyrical and virtuosic, and that I could do adagio movement and she incorporated all of that—with acting skills. She also taught me so much about how to be generous with dancers, how to run a room with command without being mean. She never raised her voice. If a dancer wasn’t working out in a part, she’d take them aside and say, “You know what? You’re a beautiful dancer, but I just think this isn’t right for you. There may be something else, and thanks for everything you did.” She just handled every situation so beautifully.

Haven’t you also worked extensively with Twyla Tharp? Outside of NYCB?

I love Twyla. When I first met Twyla, it was at one of these points in my career when there wasn’t much going on in the rep for me so I had a chunk of time. Twyla’s company had disbanded, and Stacy Caddell [a former NYCB soloist] said, “We need to get Twyla into the studio.” I met her at Aaron Davis Hall; we were in this children’s party room in the basement with glitter on the floor, no windows and burgundy walls, and I walked in and she said, “Hi, I’m Twyla, are you ready? Are you warm? Just follow.” Three and a half hours. No talking. She would show a step and I would have to imitate it or copy it. I think we’ve remained friendly because I don’t ever want anything from her. I just want to work in the studio with her. I find it so enjoyable; she’s so funny. You’re in the middle of something and she starts speaking in broken French. Or she gets upset and starts rolling around on the floor and going, “Arrrgh!” It’s very entertaining. She’s so driven and she has such a passion, and I really admire her. She’s a strong woman and very, very smart. I enjoy working with her—no strings attached.

Do you know what your plans are after you retire?

I’m going to choreograph more. I’m going to audition for some Broadway shows. This summer, I am taking a group to France, and I’m also choreographing for the dance program at the Miller Theatre in March. Thomas Lauderdale of the group Pink Martini and I are collaborating on a new work. I am working on a one-man show for myself, but my dream is to choreograph an evening of ballets to John Zorn’s music performed at Jazz at Lincoln Center. I also have a degree from the Fashion Institute of Technology. [Laughs] If the other things don’t work out, I’ll just go and design nice clothes for people.

New York City Ballet performs at the New York State Theater through Jun 29.