[title]

In the spirit of The Great Gatsby heading to Broadway this spring, we’re taking a look back at the era of the flappers, speakeasies and the Jazz Age.

The New York City of the 1920s is vividly painted by author F. Scott Fitzgerald when he mentions landmarks across the story: the Queensboro Bridge, the IRT Astoria line, Fifth Avenue, Washington Heights, The Murray Hill Hotel, Forty-Second Street, Hotel Metropole, Central Park, the Plaza Hotel, and the Corona, Queens ash heaps.

At the Plaza, for example, Jay Gatsby, Daisy Buchanan and her husband Tom, narrator Nick Carraway and his friend Jordan Baker take a trip to New York City for an afternoon in a hotel room. But lo and behold, tension is bubbling under the surface as Tom becomes suspicious of Gatsby’s relationship with Daisy. The room becomes a crucible for their relationships and is one of the most dissected scenes in the novel.

But what do we actually know about this period in New York City outside of these old landmarks? Below, we divulge 10 secrets of the NYC of the 1920s.

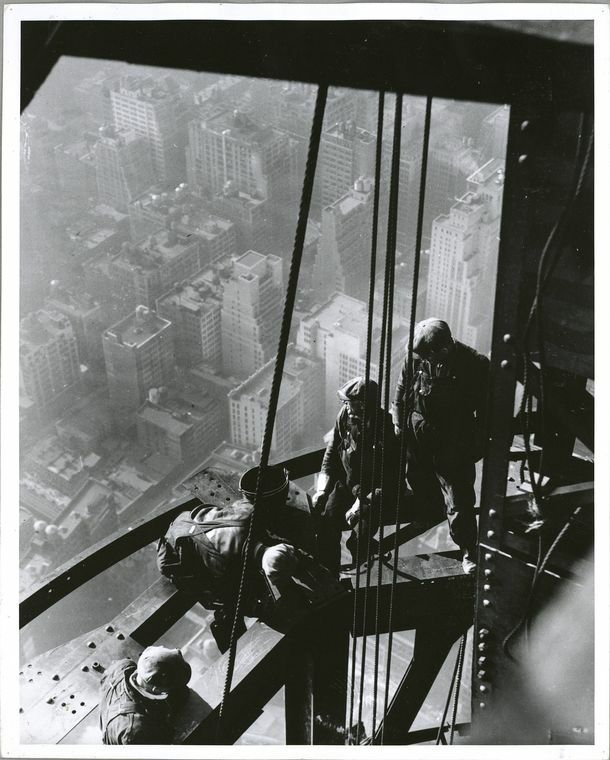

1. The city’s most iconic skyscrapers stem from this era

The Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building—the two gems in our world-famous skyline—started their construction in the 1920s. These Art Deco beauties are a product of the time though they were technically completed in the early 1930s. Their plans and designs were made during the ’20s. At first, they went toe to toe for the title of “world’s tallest building,” not far off from the skyline wars we see today. But over time, both have become landmarked giants, attracting millions of visitors to see them. Even to this day with the new cropping of sky highs like Hudson Yards, One World Trade and the pencil buildings surrounding Central Park, these icons anchor the skyline in the city’s Art Deco past when Manhattan was just becoming what we now know it to be.

2. There were thousands of speakeasies in NYC during Prohibition

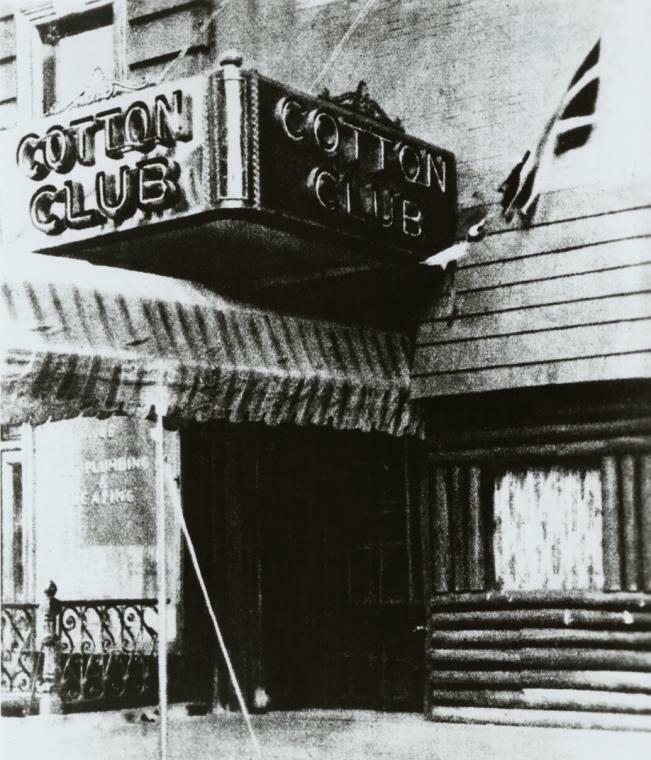

When we say “thousands” of speakeasies, we mean it. During Prohibition, when it was illegal to sell, transport and produce alcohol, there were anywhere from 20,000 to 100,000 speakeasies in New York City alone, according to the New-York Historical Society. That sounds like a lot but it’s worth noting that there’s no official count because these secret bars were, well, a secret kept off the record to avoid a crackdown. N-Y Historical Society says that Manhattan’s most infamous speakeasy hostess was Texas Guinan, who managed more than six speakeasies in her time, including the 300 Club, the Texas Guinan Club, the Century Club, Salon Royale, Club Intime and Club Argonaut. Harlem’s Cotton Club, pictured above, was also a speakeasy, but most importantly a legendary nightclub that featured Black entertainers such as Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong, Ethel Waters, Lena Horne and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson.

Related bonus secret: NYC has “Temperance fountains” that were set up by temperance societies to encourage people to drink water rather than alcohol. The thought was that if water was made accessible, they’d drink it instead. Often, the word “temperance,” the act of abstaining from drinking, was emblazoned on these fountains. You can still find them in the East Village’s Tompkins Square Park and at Union Square Park.

3. Black New Yorkers created one of the biggest artistic movements in the world

After the Great Migration, when Black Americans left the South and moved to cities in the North, Midwest and West, which started in 1910, they flooded New York City with dance, music, art, literature, fashion, theater and politics, especially in Harlem. During the movement people like Langston Hughes, W.E.B. Du Bois, Duke Ellington, “Jelly Roll” Morton and Zora Neale Hurston became household names. We have a lot to credit the Harlem Renaissance with and you can learn all about it and see some of the incredible works created during this time at a new groundbreaking at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” aims to be a part of rectifying the erasure and celebrating Black artists and intellectuals.

4. About 35% of the city’s 5.6 million residents were foreign-born

New York City has long been a city of immigrants. In the 1920s, a large portion of the population was comprised of people who had been born in another country. According to Ancestry.com, Russian Jews (480,000) made up the largest foreign-born group in New York with about 480,000 people, followed by Italian at 319,000, Irish at 203,450, and German at 194,154 immigrants. Like today, immigration law was a hot topic issue. The ancestry site says that by 1921, New Yorkers were worried about competition in the workforce and racism was rampant, leading to the Emergency Quota Act, which set limits on immigration to the U.S. In 1924, the country passed another law that made the quotes even more strict and permanent.

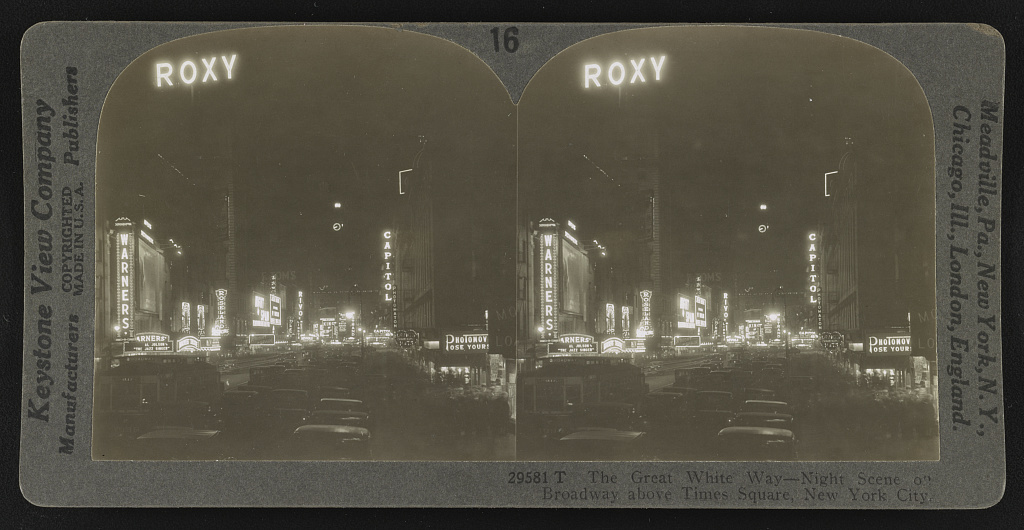

5. The world’s first “talking” movie debuted at a Times Square Theater

As always, New York is often the first place for many things to occur. It was no different on October 6, 1927, when the world’s first “talking movie,” that is with sound, The Jazz Singer starring Al Jolson, debuted at the Warner Theater in Times Square. According to Wired, the 89-minute Warner Bros. film was played using the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system with a projectionist manually syncing each of the 15 film reels to the phonograph record containing dialogue and music. That’s a lot of work! It is said that the audience “became hysterical” when they heard their first dialogue. Can you imagine?

In those days, New Yorkers could see a movie for 20 cents (and 15 cents for children), according to Ancestry.com.

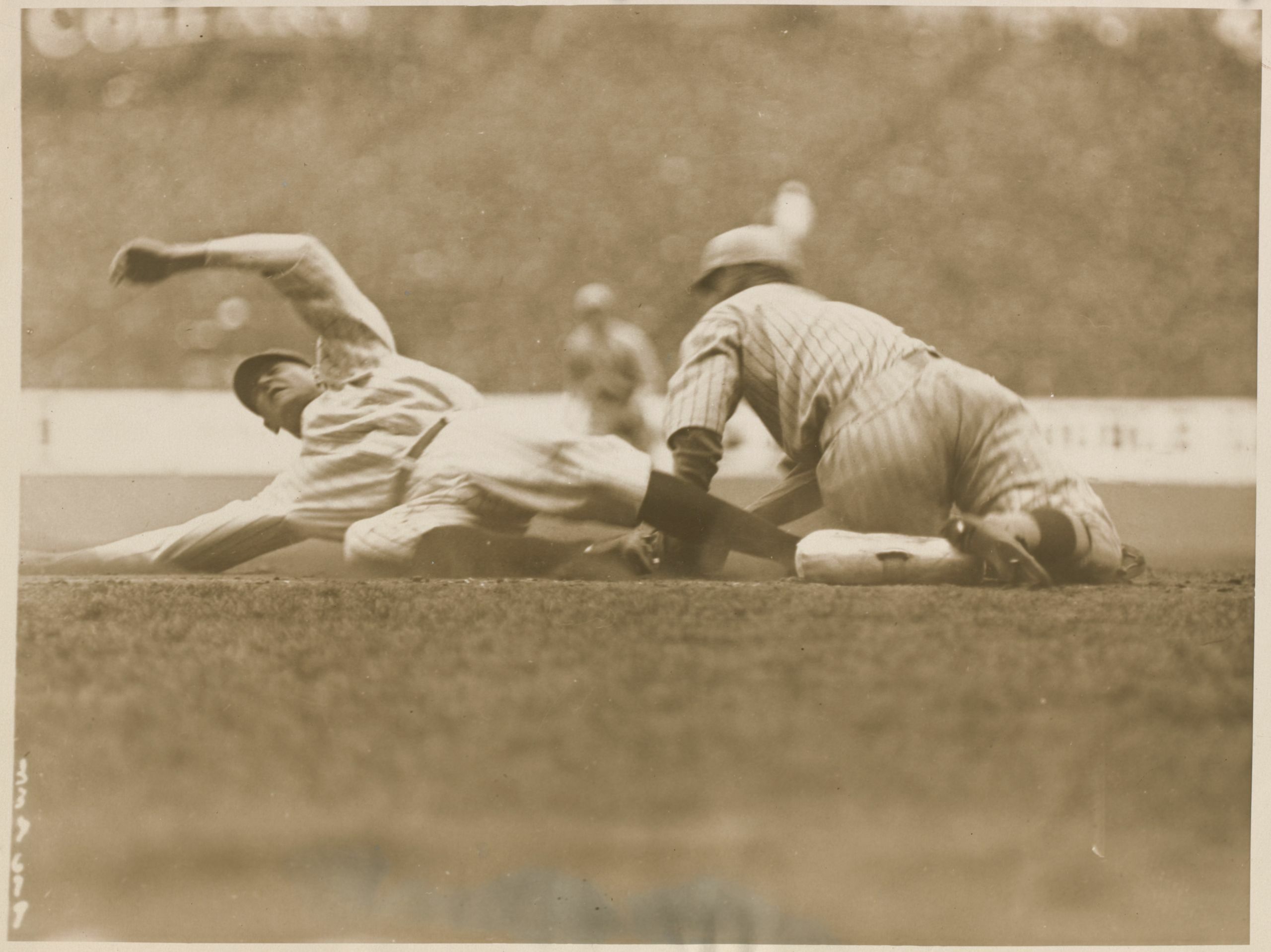

6. Bleacher seats cost 25 cents when Yankee Stadium opened in 1923

We all know Babe Ruth was a ’20s hero. The headlines that he’d be joining the New York Yankees came out on January 5, 1920, according to MLB.com. He’d go on to become one of the players on the “Murderers Row” lineup, which made for quite a golden age in Yankees territory. In fact, Ruth broke attendance records in the ’20s—the Yankees earned more than $1 million in profits and were able to make the $2.5 million to build the new Yankee Stadium.

Tickets for opening day 1923 in the new stadium cost 25 cents for bleacher seats. That’s $4.54 today to see the Yankees play.

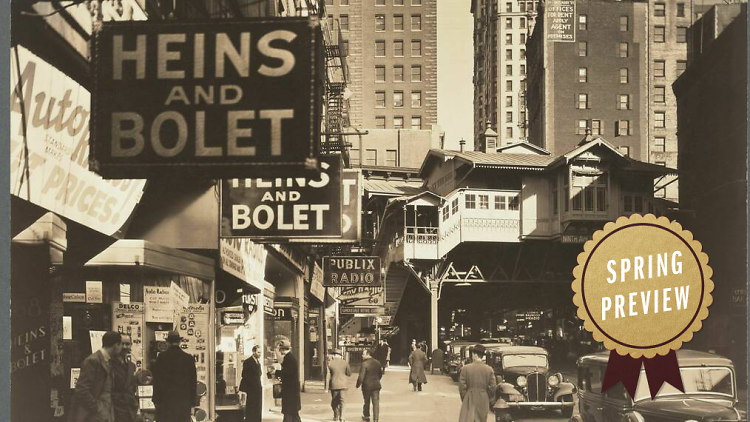

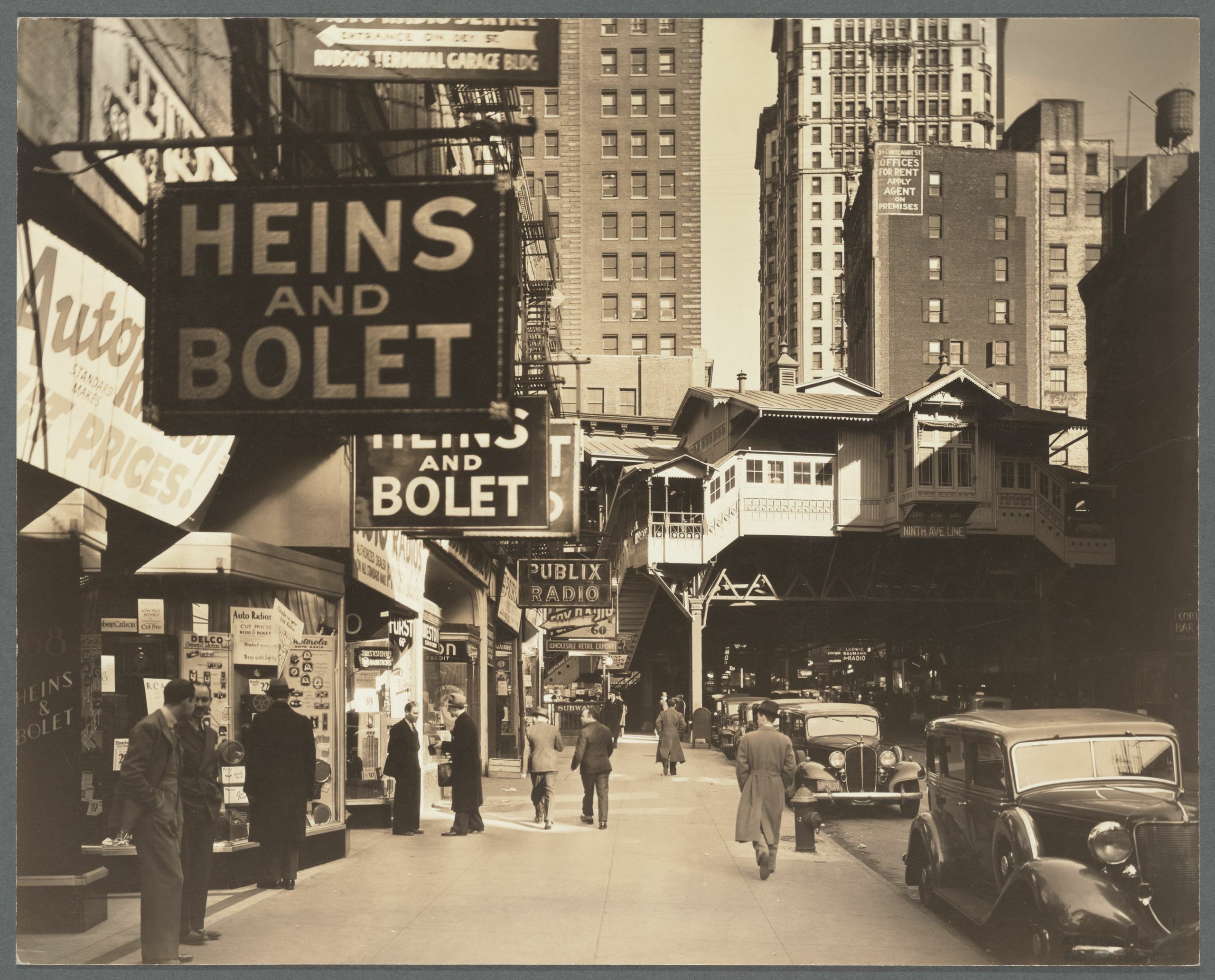

7. There was a radio district with more than 1,000 stores

We all know of the Flower District and the Garment District, but in the ’20s, there was an electronics district, called “Radio Row.” As it sounds, it was a specialty shopping district (across 13 blocks) in Lower Manhattan for radios and electronics, which had its first store open in 1921 It was located between Barclay Street to Liberty Street, and from Church Street to West Street, including Cortlandt and Dey streets. The photo above shows Cortlandt Street around Radio Row’s beginnings (note the old overhead subway station). By the 1950s, the district had more than 1,000 businesses and it’s said you could hear music blaring from it from blocks away.

8. The subway fare to Coney Island was only a nickel

You read that right! Five cents for a trip to Coney Island. Today, that’s equivalent to 81 cents! The MTA has us up to $2.90. We’ve said it a lot in this article, but can you imagine? The subway was “completed” (is it ever really finished?) in 1920, which meant that more New Yorkers than ever could make a day trip to the seaside resort. And in 1923, NYC opened public access to the beach rather than keep it restricted to the guests of luxury resorts. These developments massively changed Coney Island. More people from different walks of life and backgrounds, not just the wealthy, meant it’d change to suit the wallets of its new visitors. These folks carried nickels in their pockets, it is said, hence the new name Coney Island would take on: the “Nickel Empire.”

“The nickels in the masses’ pockets became the symbol of a new era,” writes Jeffrey Stanton on westland.net. “The mass market slowly forced Coney Island’s price scales downward. The fifty cent ride became a quarter, quarter rides became fifteen cents, and ten cent rides became a nickel.”

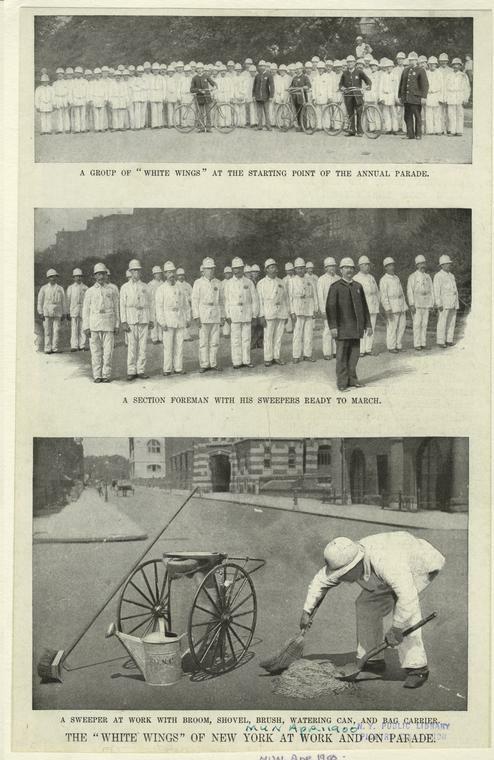

9. There was a brigade of city street cleaners called the White Wings

I’m not going to ask you if you believe it, but wow! New York City had a crew dedicated to cleaning the streets! Kickstarted in the late 1800s, the “White Wings” brigade was created to literally clear poop off the streets dropped from horses on the street.

According to N-YHS, nearly 500 tons of horse manure were collected from the streets of New York every day, which were produced by 62,208 horses living in 1,307 stables. And you thought there was a lot of poop on the streets now! Add that to dumped-out garbage, animal carcasses from butchers, and ashes, and it’s harder to get around than Times Square on New Year’s Eve! Dubbed the “White Wings” because of their all-white uniforms that represented cleanliness, this army of sanitation workers got rid of refuse and created a more sparkling NYC. They wore white until the 1930s and eventually became the Department of Sanitation.

10. Subway turnstiles were introduced in 1921

The subway turnstile has been the talk of our town for quite some time, especially lately with the invention of a new kind of machine that may (or may not) prevent fare evasion, but there used to be a time when they didn’t exist! The subway turnstile was officially unveiled in January 1921 on the Interborough Rapid Transit system, replacing ticket takers. As referenced above, you simply inserted a nickel to get through. According to ny1920.com, they were first installed at the 51st Street and Lexington Avenue Station. The IRT had hoped these new machines would save $1.5 million a year by replacing ticket takers—still a very contemporary measure.

It turns out not that much has changed since the 1920s.