[category]

[title]

Death, sex, and violence: if you think Hobart’s winter arts fest has lost its edge, you aren't doing it right

Where do we draw the line between art that is dark, provocative and challenging, and that which is outright tasteless, excessive, and wrong? Dark Mofo specialises in dancing ferociously on this tenuous edge. The Hobart festival just wrapped up its fiery 2025 return with the customary procession and burning of the Ogoh-Ogoh – a giant totem-like effigy crafted by Balinese artists – and it appears that leaning into the provocative has once again (mostly) paid off. (The Mercury is reporting that the festival’s return has been an economic success, drawing in more than $50-million dollars in tourist revenue.)

Drawing inspiration from pagan solstice rituals, the midwinter festival is all about embracing the blackness of winter, leaning into mischief and debauchery (a suitable theme for a festival spearheaded by MONA, the equally-divisive gallery that put Hobart on the map). Needless to say, I jumped at the chance to finally pop my Dark Mofo cherry this year. And while some detractors are theorising that Dark Mofo has “lost its edge”, what I discovered was a town painted red by a new-age “Goth Christmas” – and I learned that when you embrace the dark, you might just find the light.

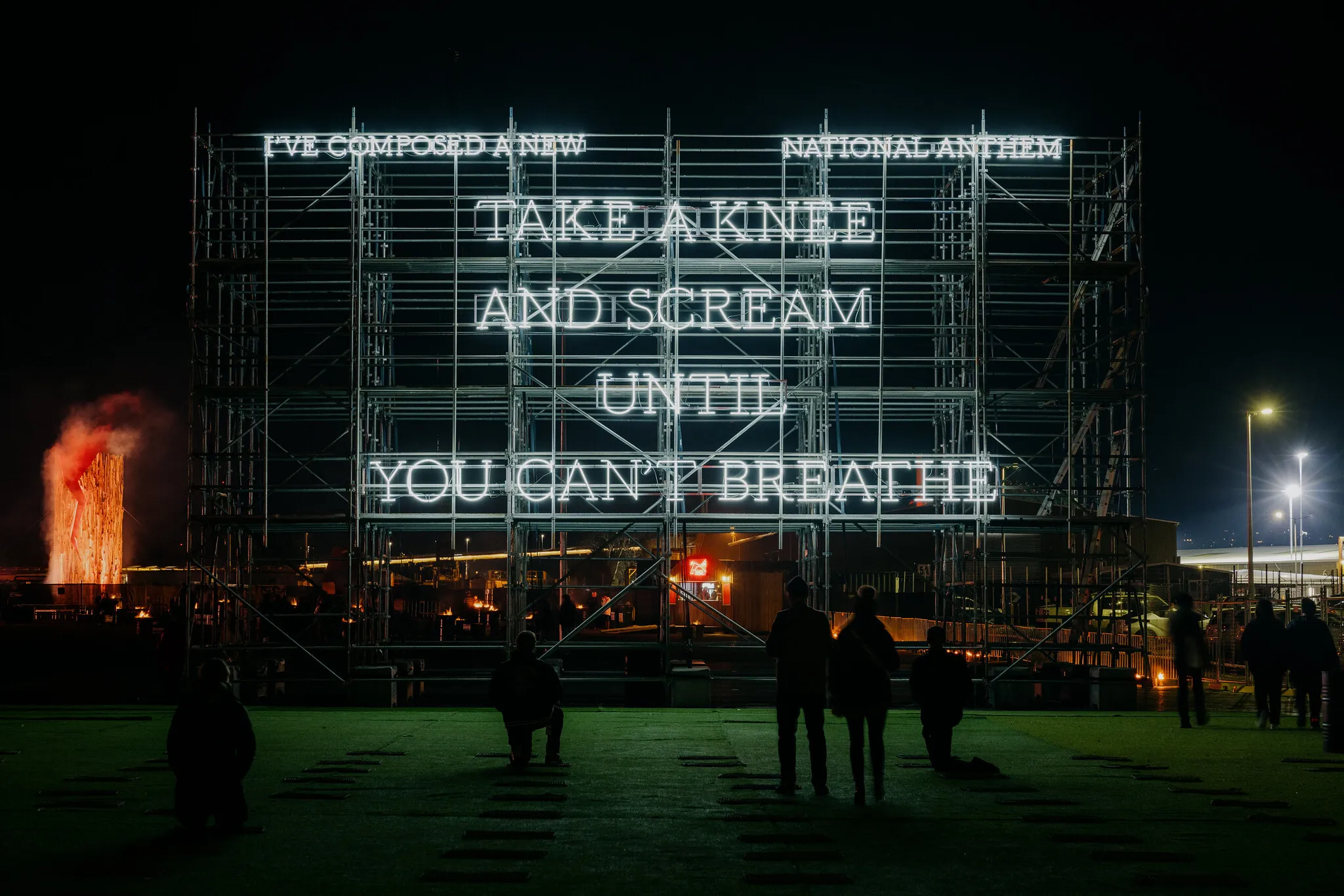

I was greeted by a discordant chorus of screams as I trudged along Hobart’s old industrial waterfront towards Dark Park (a family-friendly festival precinct marked by massive art installations and open fire pits). Just past the site’s entrance, which is flanked by towers shooting fireballs into the sky, was a billboard-sized artwork with a message spelled out in large fluorescent letters: “I’VE COMPOSED A NEW NATIONAL ANTHEM – TAKE A KNEE AND SCREAM UNTIL YOU CAN’T BREATHE”.

A theme-park-like soundscape of squeals and yells added to the festival’s atmosphere of “Disneyland, but make it dark”. I dropped to my knees amongst a sea of grown adults, small children and crackly-voiced adolescents, and emptied my lungs into a cathartic roar. I felt lighter – like I had just been given permission to open a release-valve on some of the emotional baggage I had unwillingly hauled to Hobart with me.

But later, when reading up on the origins of the artwork (‘Neon Anthem' by Nicholas Galanin, a First Nations Tlingit and Unangax artist from Alaska) I couldn’t help but feel uncomfortable about the way the piece’s original message (as a pointed statement about the tragic murders of men of colour that sparked the Black Lives Matter movement) would be left unexplored by the majority of festivalgoers that came into contact with it. (As well as Dark Mofo itself, whose one-line description of the artwork is pretty light on details.)

The main act of Dark Mofo’s opening weekend was a high-adrenaline piece of performance art, centered on two vehicles locked in a high-speed dance culminating in a visceral head-on collision. Standing amongst the spectators of all ages (some still in prams) gathered in the grandstands on the far side of Dark Park at the Regatta Grounds (where folks would usually gather for sailing events), I felt like I was witnessing the modern-day equivalent to a gladiator battle. The opponents participating in ‘Crash Body’: Brazilian artist Paula Garcia (performing the latest chapter of a two-decade-long project) going head-to-head with a professional stunt driver.

Many spectators peeled off during a tense waiting period where nothing much happened, but when the drivers finally took off, the action was swift and explosive. Being stuck at the back of the crowd and cursed by my modest height, I didn’t manage to see the moment of impact, but I heard it – the unmistakable smack of machine against machine – followed by a rising plume of white smoke, and a spontaneous roar of cheers and applause. Waiting around for the performance to start in earnest may have been uncomfortable, but that was nothing compared to the stress of the wait for the artist to emerge from her car. The stunt driver extracted himself quite quickly, but a sense of unease settled over the crowd as we waited for Garcia to be freed from the crumpled car. (“What if she’s, like, is actually hurt?”) The cheers that erupted when she did, eventually, get out and wave were next level.

How ethical is it to perform a very-possibly-deadly stunt to a big crowd? Especially when car accidents needlessly claim so many lives in this country? I haven’t quite made my mind up about this – but any spectacle that can draw rev-heads and connoisseurs of the Fast and the Furious franchise to take an interest in art will certainly get a nod of approval from me.

After the prams packed in for the night, Dark Mofo’s adults-only antics kicked on at Night Mass: God Complex, a “temple of unrest” and “shrine to excess” in a secret location – aka, an enormous rave taking over what savvy punters have deduced to be a former Hillsong hub, and also sprawling out into a closed-off street.

In one room, a pair of felt puppets dressed up as a nun and a festooned priest held court from above a central bar, hurling hilarious insults at punters like a more sacrilegious answer to those old geezers from The Muppets. In another room, DJs hyped up the crowd from a dynamic stage surrounded by screens and glowing Matrix-esque tubes. In the largest space, a procession of excellent bands and live acts played from two alternating stages on a constant loop – one above the crowd, and one on their level (note: balcony stages are underrated, we need more of them!). And upstairs, we were invited to enter a maze to discover mystery art and performers – including a real nude person nestled in the body of a decaying oversized shark, and a barbershop manned by a lingerie-wearing drag queen on a mission to shave off the eyebrows of willing(?) volunteers.

Goths bumped elbows with ravers in outfits rigged with strobe lights, eshays, art girlies and middle-aged couples. I was reminded of some of the best nightlife I’ve ever experienced: Marrickville warehouse parties where you’d be texted the location at the last minute, the unmatched glory of a queer club on a good night, the infectious untz-untz of a remote bush rave, and the hedonic dancefloors of the now-retired Hellfire Club (pour one out for Sydney’s longest-running fetish themed nightclub).

However, and this is just my personal experience – I was also reminded of how much better nightlife can be when it’s centered on a particular subculture or group. When queer performers dance to straight-leaning audiences, it just isn’t the same. When I overhear bros on the dancefloor cracking fat jokes, it doesn’t feel like we are all fam in this clerb, in fact. (And I’ll add, when I can’t find a cloakroom at an event on a chilly winter night, I’m gonna get shitty about carrying around my coat.) Night Mass (and Dark Mofo as a whole) is optimised for a broad audience to get a taste of the subversive. That’s not necessarily a bad thing – I believe that everyone is better for having a subversive nightlife experience – and it is quite successful at what it sets out to do. (And I’ve noticed that many artists and performers I admire have been booked because of it, to boot.)

At many spots around Hobart, you can pick up a free map for Dark Mofo’s ‘Art Walk’, which will lead you into all sorts of interesting nooks and crannies to discover works that are strange, beautiful, and also so deeply disturbing that you might find yourself questioning where the line crosses to full-blown trauma porn.

From a rooftop on the harbourfront, a gargantuan human hand with a face glares down at festivalgoers (that’ll be ‘Quasi’ by New Zealand artist Ronnie van Hout). In a decommissioned church, a giant, pale, pixie-like creature squats in front of an old organ, razor-sharp teeth are bared from behind its pouting lips (Travis Ficarra’s ‘Chocolate Goblin’ – a highlight for me). Opposite this figure emanating desire and disgust, a pre-recorded performance video depicts a woman (who looks sort of like the little girl from The Ring grew up) delivering a deep, guttural vocal performance that transcends metal to a meditative state (‘Mortal Voice’ by Karina Utomo and Cura8).

In an abandoned-seeming corporate building, visitors climb the stairs to find a screening of a real performance in which the artist (naked and exposed) is hanging from a noose, and his audience must work together to hold the weight of his body and prevent him from asphyxiating (Carlos Martiel’s ‘Cuerpo’). Quietly troubling, Martiel’s piece is designed to echo the violent public acts of lynching in 19th and 20th-century America (and I’m not so sure that guy who went in at the same time as me should have brought in his young sons…).

In the same building, in an experience I only learned of secondhand, an artwork invited viewers to walk down a narrow passageway and squeeze past a man dressed in all-black who would violently swing around a police baton, beating on the walls (Paul Setúbal’s ‘Because The Knees Bend’). It is things like this that raise uncomfortable questions about the festival’s “theme park of trauma” approach. There are far too many people who don’t need to seek out art in order to understand the threat of violence, either from a guy who looks like a riot squad cop, or otherwise. With devastating conflicts and active genocides playing out while politicians wring their hands, and headlines of atrocities flash in our newsfeeds cushioned between thirst traps and Labubu-core recession indicators, what do we get out of replicated violence? Is it enough that it starts a conversation?

Taking the crown for Dark Mofo’s most horrifying artwork this year is Indigenous Tasmanian/Trawulwuy artist Nathan Maynard’s ‘We threw them down the rocks where they had thrown the sheep’. I joined a short queue on a regular street, and descended into the musty, dimly lit basement of an old furniture store to discover rows of industrial shelving filled with a total of 480 jars – each of them holding a real, preserved sheep head. A confronting display (even for a casual taxidermy enthusiast like myself), Maynard’s installation goes a lot deeper than gore – using flesh to "lay bare the legacy of cultural theft and erasure" and call attention to the remains of First Nations ancestors from around the globe "languishing in museums and their storerooms”.

The artwork makes direct reference to the 1828 Cape Grim massacre, in which about 30 Aboriginal men were killed by four shepherds – one of many mass killings of Indigenous people during a period in Tasmania known as the Black War (1824-1832) – solemnly calling attention to the horrors of colonial violence. This artwork’s provocative approach raises a lot of ethical questions, including whether it should have been presented at all. But, it certainly got people talking, and if anyone has a right to take control of this narrative, it’s an Indigenous artist from Tasmania.

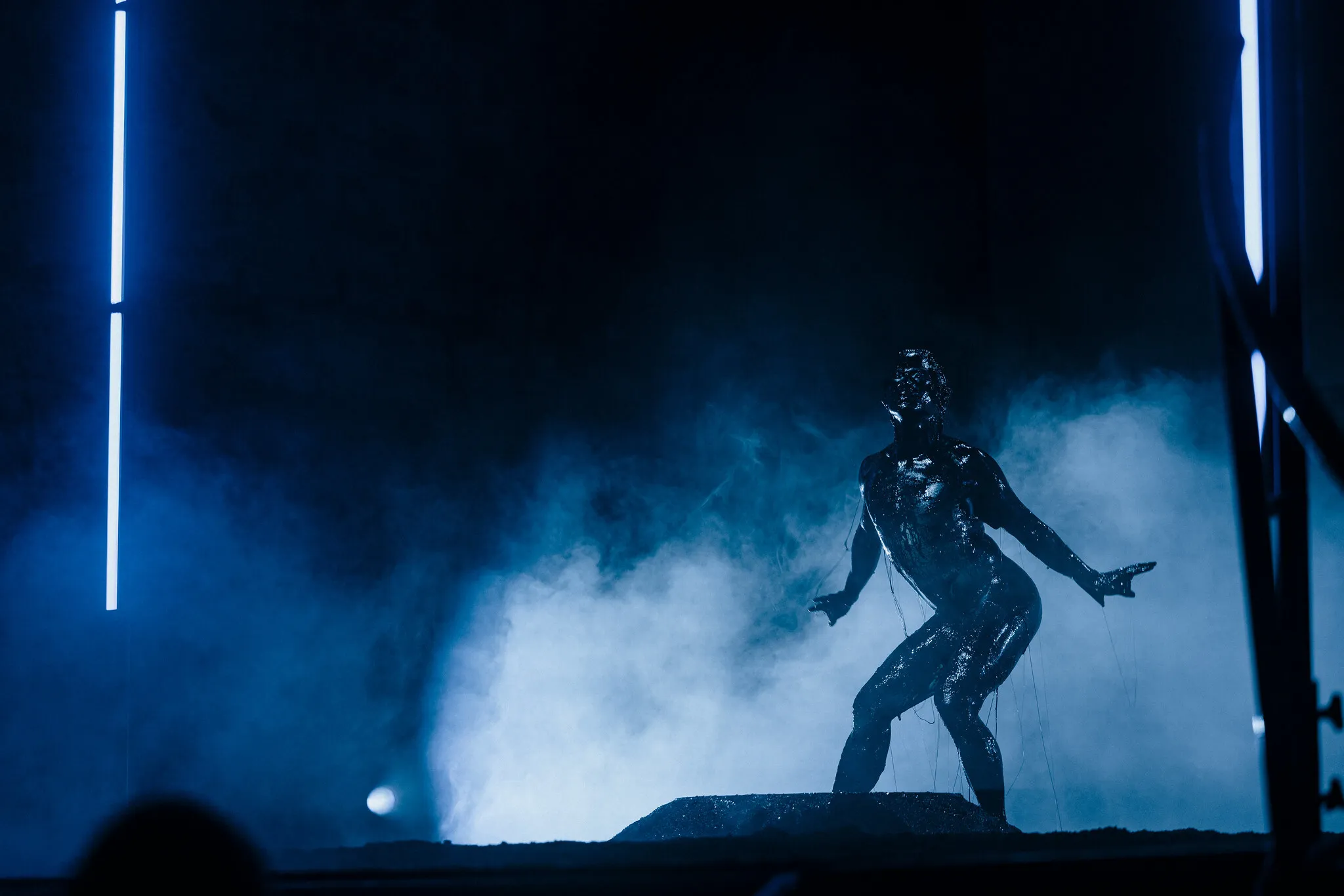

Meditative, strangely alluring, transcendently beautiful and somewhat intimidating – Joshua Serafin’s VOID will live on in my subconscious for some time. Drawing on this multidisciplinary artist’s Filipino heritage and tapping into a divine queer energy, VOID is a performance complete with a “splash zone”. (The first few rows of the audience were actually provided with plastic ponchos, and the heritage chairs they sat in at Hobart’s Theatre Royal – the oldest continually operating theatre in Australia – were also plastic-wrapped.)

A suitable fit for the Dark Mofo brief, the piece challenges its audiences with its mystery and slow build. After a lengthy instrumental segment, Serafin emerges – nude, writhing, and illuminated by blue poles of light – to execute a ferociously charged dance punctuated by yelps of passion and rage. Then, following a brief video segment, the piece builds into one of the most stunning displays you’ll ever see. Serafin covers their body in a strange, black viscous liquid that’s whipped through the air, and some is even flung onto unsuspecting audience members (seated a row behind the sanctioned splash zone, the person sitting next to me copped a wallop of goo). The mystery liquid catches the light in a dazzling way, and the sound of it splashing and smacking on the stage intermingles with the pant of the performer’s breath and the immersive music. This is the quality performance art that you want to see platformed at an internationally-recognised festival.

In the gloom of a subterranean gallery at MONA, sparks are flying – liquid metal to be exact, heated to 1500°C, dripping down from the ceiling in dramatic waves of firelight. Without the fireproof screen standing between me and this transfixing spectacle, this would be a disastrous encounter. But it’s actually another more unsuspecting piece in this exhibition that is more likely to disfigure me. As I approach a big block of wood clamped by an odd mechanical device, a gallery attendant warns me not to stand too close – this artwork is designed to break. In the opposite corner, I spot a pile of splintered hunks of wood cast off from previous days. I wonder how large the pile will grow by the time the exhibition closes in April.

MONA unveiled in the end, the beginning, the first Australian solo show from Italian artist Arcangelo Sassolino, alongside Dark Mofo’s other provocations. It feels reductive to simply refer to Sassolino as a sculptor. Channelling his interest in mechanics and technology, he creates dynamic, kinetic pieces that test the laws of physics – using force, tension, speed, heat and gravity to create dramatic transformations. Aside from the fiery spectacle of the collection’s title piece, this exhibition is actually rather quiet and contemplative. As the artist toils to “free matter from a predetermined form”, we are prompted to ponder how we can push and shape ourselves, our circumstances, and perhaps even the world around us beyond what keeps us stuck.

With only a few days to explore the excesses of Dark Mofo, I didn’t find the time to write down my fears on a note to be burned up with all the others stuffed inside the Ogoh-ogoh effigy before it was set alight. However, I did stumble into my own unexpected ritual of release. The culprit? The ‘House of Mirrors’. After touring all over the country, this kaleidoscopic maze created by Australian installation artists Christian Wagstaff and Keith Courtney has stood on the grounds of MONA since 2016.

As I made my approach, the attendant outside the gate informed me that some people figure it out in two minutes, while others could take upwards of twenty minutes. (I fell firmly into the latter category, as did many people I continuously bumped into on the inside.) As I cautiously rounded corners, confronted by kaleidoscopic multiples of my own reflection, I became increasingly discombobulated by the maze’s dizzying passages. I wound up back at the entrance more than once, and the temptation to give up and take the easy escape was real. But something called me back into the unknown. Despite my weariness, I was determined – and yes, finding my new direction involved taking some wrong turns and a terrifying amount of uncertainty. But I pressed on, energised by the darkness and decadence I had spent the weekend immersed in – and eventually, a new stream of light emerged, and I had found the way to the other side. I felt a quiet sense release upon the realisation that I had freed myself by following my own winding path, and it was more satisfying than retracing my steps ever could be.

Rather than fighting it, Dark Mofo embraces the chilling darkness of winter nights. Random shopfronts are illuminated by the festival’s signature hue of glowing red as you navigate your way between experiences.

Dark Mofo is able to tap into something that other winter festivals in Australia haven’t quite been able to capture. It could have something to do with Hobart’s size – the vibe is more like a big regional town than a capital city, which balances expectations (the quiet patches between activations and lively venues feel less stark than the lulls in the Vivid Sydney lightwalk, for example).

It could also have something to do with the festival’s themes – audiences expect the art to be provocative, challenging, dark, and divisive – you go in knowing that it might not be your cup of tea, that it might even be intended to leave you feeling a little sick in the stomach, and thus, you’re less likely to feel let down, compared to something that promises a grand dazzling spectacle. Not that Dark Mofo is devoid of spectacle – quite the opposite, actually.

Similar to the Biennale of Sydney’s 2024 theme, which leaned into the transgressive origins of carnival – Dark Mofo speaks to our need for ritual, for celebration, and to be connected with others in order to move through change and confusion, process pain and grief, and to cope with the exquisite ecstasy, agony and mundanity of being alive. After making my first pilgrimage, I for one, can say that I’ll be back for more.

Stay in the loop: sign up for our free Time Out Australia newsletter for more news, travel inspo and activity ideas, straight to your inbox.

Discover Time Out original video