Inside his studio at The National Gallery, I discover George Shaw pissing up a tree. A painted version of him, anyway. The real-life Shaw is hesitant about calling it a self-portrait. ‘It might be me,’ he says of the stooped, raincoat-wearing figure. Self-portrait or not, it’s a curveball from the Turner Prize-nominated artist, who’s spent his career painting the same deserted provincial landscape again and again: the Tile Hill area of Coventry where he grew up. In an age of ironic and nudge-wink art-making, Shaw’s avowedly sincere pictures of council houses, shut-down pubs and rain-sodden car parks have always been something of an anomaly.

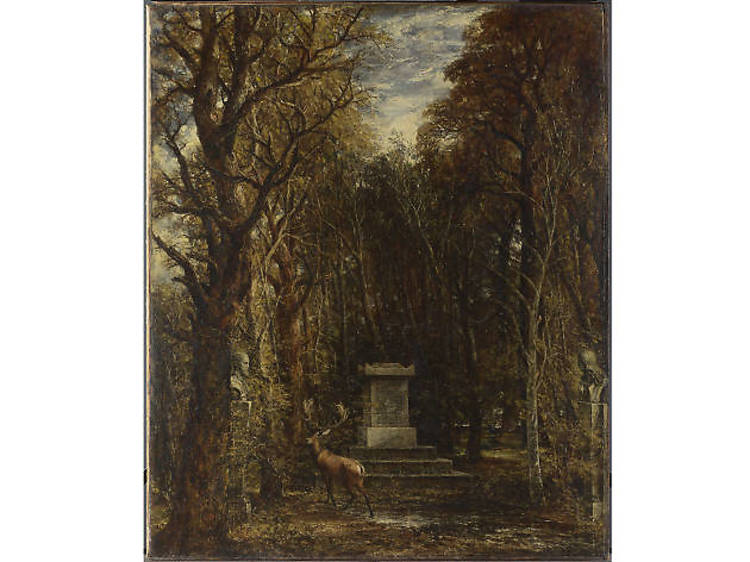

Then he was invited to embark on a two-year residency at The National Gallery – and on first glance at the 30-odd woodland scenes he’s painted since, you might think he’s finally let go of the suburbs. But closer inspection reveals some curious details. There’s a strewn heap of jazz mags in one painting, a graffiti cock gouged into a tree in another. Civilisation, it seems, isn’t far away.

‘The brief was to respond in some way to the collection’ Shaw explains. ‘I found myself drawn to the paintings of nymph and satyrs, bathing by pools and messing around. They’re about transgression. And I started to think about the woods near where I lived in the ’70s, where people would drink, smoke, lose their virginity. My first experience of the nude in the landscape wasn’t Titian’s Diana – it was finding pornography there.’

Hardly the sort of thing that should go on display at the grand old NG, you might think. But Shaw says it’s been there all along. ‘There’s lots in the collection that’s masquerading as high art, but is really just titillation. The collection’s about the two great themes of life: sex and death. And what I’m doing with these paintings is creating my own mythology, piling the woods with stories. That’s what art is: a way of re-enchanting the world.’ Read on for his thoughts on three of the paintings that have inspired him.