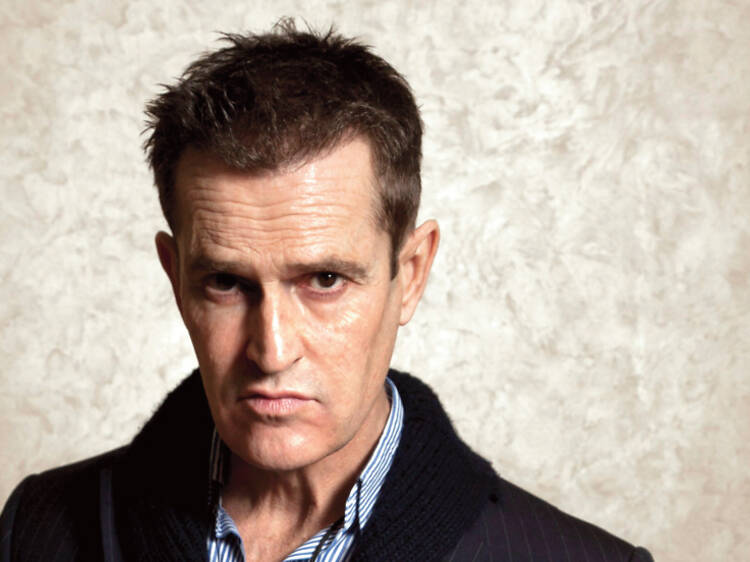

Yet today, in a back corner of his favourite Soho café-bar, wearing tracksuit bottoms, trainers as big as boats and a scarf wrapped twice around his throat, Everett is going out of his way to distance himself from the part. ‘I’m not like Wilde,’ he insists. ‘Wilde was an absolutely brilliant writer and thinker. One of the great intellects. I’m a floozy with pretensions.’

Clearly he’s not. Everett’s Wilde is a bulky, sombre figure, relentlessly employing the power of language to create a still point at the centre of a swirling storm of hysteria and hypocrisy. It is a performance of utter maturity, craft and seriousness; it may even verge on greatness. In the first act of ‘The Judas Kiss’, which is coming to London after a UK tour, Wilde awaits arrest in the Cadogan Hotel with Lord Alfred ‘Bosie’ Douglas, the lover who has brought about his downfall. In the second, two years later in Naples, the broken, post-imprisonment Wilde duels with Bosie as he faces an end, in Everett’s words, ‘sitting pissstained in a bar on a street corner waiting for someone to buy him a drink and seeing people who used to love him cross the road to walk past’. At 53, Everett is seven years older than Wilde was when he died, and no one’s crossing the road to avoid him. His second volume of memoirs, published this year, has been as well received as his first and in the last two years he has shone as Mark Tietjens in Tom Stoppard’s BBC adaptation of Ford Madox Ford’s ‘Parade’s End’ and been cast as Henry Higgins in ‘Pygmalion’ at the Garrick. He’s particularly pleased with Tietjens (‘I felt something happened, a kind of gravity that I was trying to get to. I was thrilled…’), another weighty performance from a man who has been unfairly marked out as a flibbertigibbet since his rise from young British hopeful to Hollywood fixture in the ’80s. ‘It’s probably my fault,’ he says. ‘I think I am as serious as anyone else and just looking serious isn’t necessarily being serious. I’m not into the wank of being an actor.’

Roles like Camilla Fritton in the St Trinian’s films are not likely to counter any charges of flippancy, but when he does approach a major part he still meets critical resistance. ‘My Henry Higgins was a music-hall ghoul,’ he says, ‘a Hammer horror character. He stalked Eliza Doolittle; he didn’t stab her but he fucked her mind. The reviews all said I was a ghoul, but they said it as an insult, like I was out of touch with the reality of the play. I got reviewed for being kind of stupid. I’m still perceived as bubbly, effervescent, wonderful me.’ That ‘effervescence’ in Everett has often hidden darker things. As the almost archetypal promiscuous posh boy, he lived in utter fear of Aids in the ’80s. ‘For someone who from the age of 16 onwards had feasted on one of the most libertine periods in human history, the dawn of Aids was like being a cartoon character running off the edge of a cliff,’ he says. If you want to see what that looks like he suggests watching a 1983 mini-series called ‘Princess Daisy’. During filming, Everett became convinced he had Aids. ‘I couldn’t give a fuck about the scene,’ he recalls. ‘Terror was really what I felt. But I was a very interesting actor because of all of that. Fear is good for close-ups – it transmits the best quite often. But I could be hysterical and quite difficult.’ Does he wish he’d been kinder to people? ‘I was a kid! I’d have liked people to have been kinder to me!’

Sex and its potentially disastrous consequences provides one of the many strong links the play makes between Wilde’s era and our own. ‘Sex is still regarded as a sin,’ Everett observes. ‘There’s an extraordinary conservative undertow at the moment.’ Isn’t that understandable given recent revelations? ‘But Jimmy Savile and society were in cahoots,’ he says. ‘Everybody knew, nobody cared. This is what we have to look at. It’s a Wilde thing that’s in our play, which is that there’s no morality in “The morality of society”.’ Realising that the late ’80s Hollywood of the Brat Pack and John Hughes ‘wouldn’t have a role for a tall, thin cross between Snow White and Anne Frank’, Everett headed to Europe and a further absence that also partly explains his strange lack of prestige in Britain. ‘I ended up performing in the theatre in French as Wilde and having great success. However in this country, or anywhere, if you’re not there you’re not there.’ But he is here now: the best actor we don’t know we have. An angular figure with drawn skin and impeccable manners, his bearing carries the mark of his social class as much as his sexual orientation and he expresses an almost aristocratic concern for those Londoners less fortunate than him. ‘Everyone is more coiled and edged, ready to spit at each other,’ he notes sadly. ‘It’s a warlike stage, everyone’s very angry.’ But he explodes when I suggest this might seem so just because he meets more ordinary people now. ‘How patronising!’ Is it? ‘Yes, really and truly!’

Still, it’s a good time to be posh in England. We are culturally obsessed with the upper classes and, as in 1895, they run the country. Everett, an old boy of Ampleforth College, only a notch down from Eton, is one of them. ‘Actually I’m not,’ he counters. ‘The generation of conservatives under me is much more poisonous than my generation. And this government is ludicrous, it’s like a rock group from Cirencester going on “The X Factor”: “Yah! It worked in Cirencester so it should work here!” Yes, there’s still a class system but it’s more than that. We are about to become like the Indians were during the British Empire, a service station to a new class, the uber-rich. The face of London is totally changed.’ So where does a fiftysomething actor accomplishing some of his finest work fit into that new London? ‘Oh, courtier!’ he cackles. ‘Major arse-licking and being court jester to some oligarch. We won’t be able to afford to live here because they will have priced everything out. So we’ll be commuting in to lick arse.’

For now Everett will be employing his tongue in an utterly convincing portrayal of a genius broken on the wheel of public morality. Yet still, I suspect, he will leave us wondering just how serious he is about it. ‘The point about historical characters,’ he says as if to prove this, ‘is they are there for all of us to invent ourselves. David’s version of Wilde is how I imagine him mostly: really very heroic, and for me that heroism was that he was also an idiot.’

Discover Time Out original video