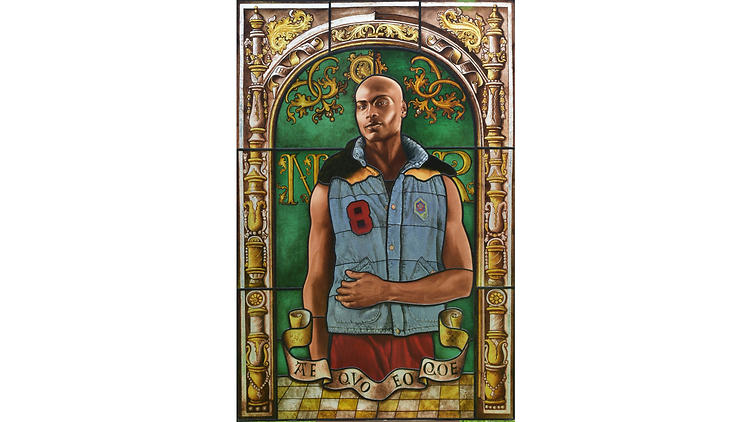

Wiley has made his name as a painter by limning portraits of African-Americans (some recruited by the artists from off the streets) in a grandiloquent style worthy of the Old Masters. While his approach is ostensibly meant to undermine the artistic biases of Eurocentric culture and white privilege, this 14-year survey of his career demonstrates that the real pleasures of his baroque style lie in his evident technical skills and in his frequent use of richly patterned backgrounds meant to recall opulent wallpaper or tapestries.

Since 2001, Kehinde Wiley has mixed references to hip-hop with Old Masters portraiture. Wiley’s paintings and sculptures investigate race, power and the politics of representation, to which Wiley adds classical technique and compositional brio. With his first museum survey opening at the Brooklyn Museum, the Los Angeles native offers his thoughts on how the racial divide between art-world elites and the broader art audience impacts appreciation for his work.

You first began making the work you’re known for during an artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2001. How much of an effect did the neighborhood have on you?

Harlem was major! You could see fashion trends and the way that people flaunted themselves, all of which began to inform my painting. I started inviting people from the street to pose.

What drew you to portraiture?

When I was a kid studying art, I’d go to the Huntington Library and Gardens and see these amazing 18th- and 19th-century portraits. I became fascinated by what they stood for, and consequentially began to wonder why people like myself were absent within the context they represented.

When you first started painting young black males—and later, women—it was almost as though you were trying to convince white viewers to see them as noble, instead of as the usual racial stereotypes. Was that your intention?

I don’t believe I’m changing anyone’s mind. The people who clutch their pearls and cross the street still clutch their pearls and cross the street. By and large, those same people are my collectors. Often, I’ll go to their homes and find that the only brown or black presence is in a painting. But art is much more than a high-priced luxury good. What excites me the most is seeing how contemporary art can speak to people who aren’t part of the elite.

That’s interesting, because your 2005 painting of a young black man on horseback, mimicking David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps, has been hanging in the Brooklyn Museum’s lobby for nearly a decade. It’s probably inspired many young people of color to see themselves in that light.

It announces that it’s okay—that you can envision yourself on the walls of this big, cultural institution. I remember wanting that as a kid. I’m happy that it’s a reality now, not just at the Brooklyn Museum but wherever my work is hung. Not that there aren’t other artists picturing people of color, but there’s something different about my work, because it references the attitudes and dress code of hip-hop and the dominant American cultural temperature right now.

How do you find your models?

In Brooklyn and Harlem, I simply stopped people on the street, because this is a culture where you expect that. It’s this just add-water, post-Warhol, Paris Hilton sense of celebrity: This is my moment of fame. It’s tougher now, because my art has become this global project, where I can be anywhere from Sao Paolo to Sri Lanka. When I was in Israel, I wanted Ethiopian Jews, so we knocked on people’s doors. In the Congo, I went to a village and spoke with the elders, asking them about recruiting some of the young members of the community there.

Your subjects are almost always placed in front of richly patterned backdrops. What determines those?

In America, it’s based on Western art history: If I borrow from French rococo for a painting, the background will be rococo filigree. When I travel, however, things from the marketplace or landscape inform the patterns.

When you’re operating around the world, how much advance work do you do? Who’s involved in helping you?

We do try to do as much as possible, but nothing is better than simply showing up and being there. There’s me, the portraitist, and then there’s me, the operation, mobilizing in all of these different places. I’ve got a large team helping me, not only in Brooklyn but also in Beijing and in Senegal, West Africa, where I’m building a studio. They do everything from painting the backgrounds to lighting and photographing the models to digitally retouching the images I use. People assume that what you see in my work is what you get. That’s true, but I’m also in the gorgeous-picture business! I want to create something seductive and alluring to serve a broader purpose.

Why have you titled the show “A New Republic?”

The American idea of freedom has always excluded black people, so in terms of its founding principles, our republic has always been broken. I’m trying to imagine a new republic where the promise of America is lived out, if not in real life, then in this sort of imagined space that painting represents, which might, in some small way, affect the trajectory of culture.

Kehinde Wiley opens Fri 20 at the Brooklyn Museum.