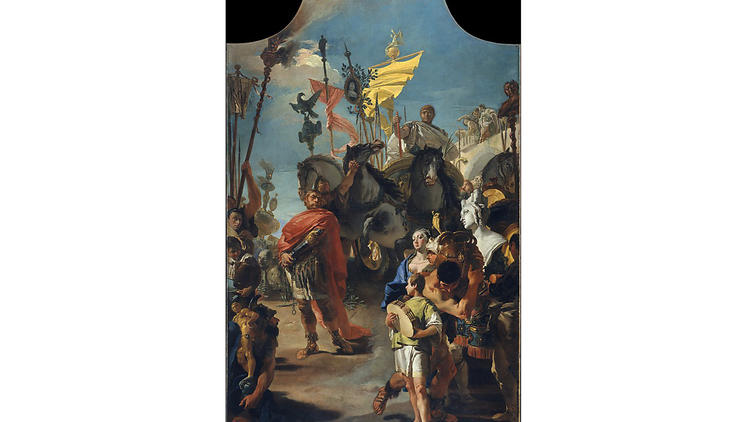

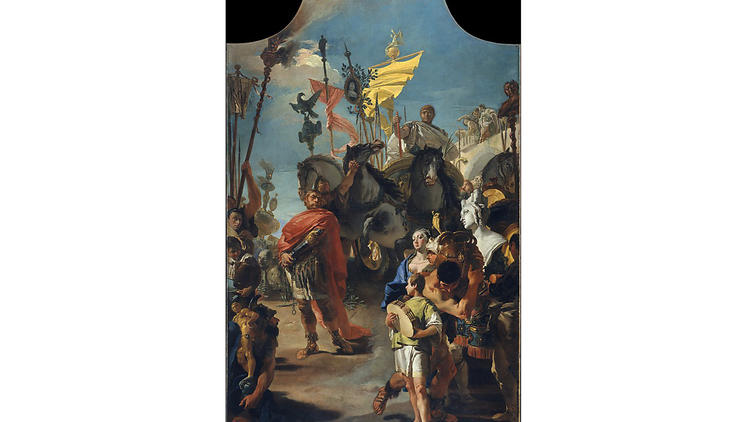

20. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, The Triumph of Marius (1729)

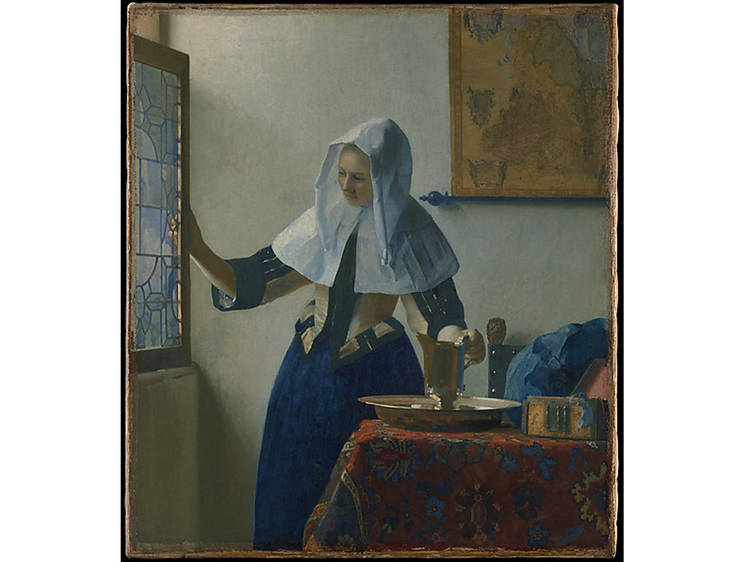

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is a veritable universe of treasures, from tiny golden pins to an entire Egyptian temple. But the heart of its collection remains the Old Master paintings located in the 32 rooms at the top of the Grand Staircase. Spanning five centuries of European art history, roughly 1300 to 1800, they represent the years leading up to the Renaissance, the great flowering itself and its aftermath, when artists had to contend with a legacy that included pictorial perspective and the naturalistic depiction of the human figure. It was a template that remained unchallenged until the advent of modern art. These works still have a lot to say to contemporary viewers, about the human condition and the meaning of art. With that in mind, here's our countdown of the top 20 Old Master paintings currently on view at the Met.

Discover Time Out original video