In ballet, it's the end of an era: Ethan Stiefel, the virtuosic star of the film Center Stage and former principal dancer of New York City Ballet, appears in his farewell performance at American Ballet Theatre where he's danced since 1997. He's already settled into his next career: artistic director of the Royal New Zealand Ballet. In this exclusive interview, he talks about his new position, why dancing is the best thing on earth and why there needs to be a ballet about beer.

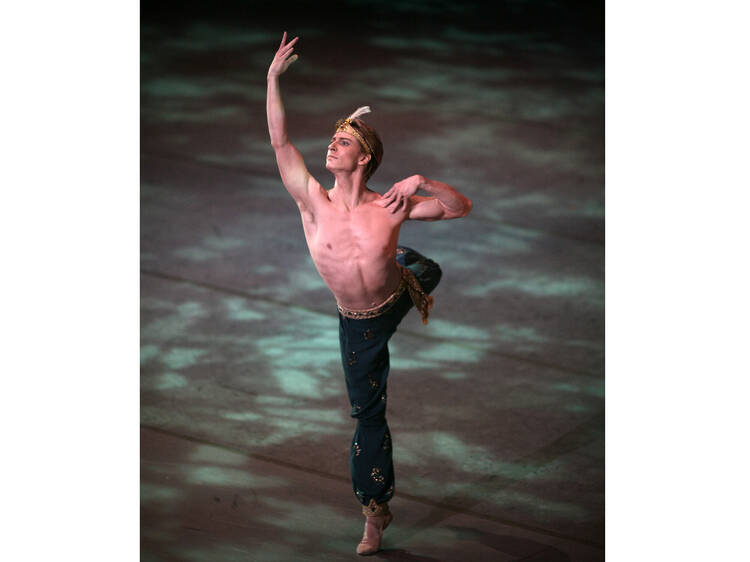

There’s more to Ethan Stiefel than dancing—he was the lead in the film Center Stage, as well as the dean of the School of Dance at North Carolina School of the Arts—but that is what he will miss most of all. One of ballet’s all-too-rare American stars, Stiefel became the artistic director of the Royal New Zealand Ballet last fall; that, along with injuries, has made it difficult for him to continue as a principal with American Ballet Theatre. Unsurprisingly, Stiefel, who was a revered member of New York City Ballet before switching over to ABT in 1997, is going out with a bang: He’ll perform his final show with the company on Saturday 7, playing the sexy slave Ali in Le Corsaire. It’s not an easy part; but Stiefel hates easy.

What made you decide to stop dancing?

I don’t think it’s really a matter of wanting to stop. In thinking about this over the last couple of weeks, especially as I’ve become more focused on the training, this is the right time. I can still go out there and deliver the physical, technical things in a way that I’d like to do them; at the same time, the maintenance that it takes to keep my body together in order to achieve that—it’s exhausting. And the pain is there—as I touch my knees. [Laughs] If my body wasn’t in this place, I don’t think I would have contemplated stopping dancing. But I can go out there and give it a really good go and leave on a top level. I wasn’t ever interested—even thinking back 10 or 15 years—in just kind of decaying. And you know what? How many people have an artistic directorship to look forward to?

Do you think that you would have had so many opportunities outside of dancing if you had stayed with New York City Ballet?

I’ve thought about that, definitely. It was a really hard decision to leave City Ballet. I love the company and the repertoire, and it’s such a big rep. Even though I’d done a lot in the six years I was there, there was still plenty to do. But to be honest, would I have gone on to perform with the Royal Ballet or the Mariinsky or even made Center Stage? Somehow, it just so happened that all of those things started coming my way two or three years into being at ABT. That shift played a part.

Do you think it’s just that ABT is more internationally known?

At Ballet Theatre, you definitely have your stars, and if you’re a principal, there’s a persona that comes along with it. I think that star quality puts you in a different place as far as doors opening is concerned. At City Ballet, it’s not that the dancers don’t have that star power, but the choreography and repertoire has always been viewed as the primary star. I’m not taking anything away from the dancers, because they’re awesome. Really, it’s about presentation. I think when you become a principal dancer at ABT, you’re presented in a different light that is conducive to opening doors, and the repertoire as well—as far as the Swan Lakes, the Giselles, the Bayadères—those ballets are the ones I was hired to dance as a guest. Those roles are a real natural conduit to the guest circuit.

It’s true. So how do you want to present the Royal New Zealand Ballet? Will you focus on the dancers or the rep?

For the Royal New Zealand Ballet, it’s both. It’s about having dancers that are technically strong with engaging personalities. But I think that the repertoire has to be unique and special—and also that the dancers inform the repertoire, and the repertoire informs the dancers. When you have both coming together, you basically have a company that has its own identity.

It’s more City Ballet, then.

[Laughs] Maybe. Well, you know, [NYCB’s master-in-chief] Peter [Martins] and City Ballet gave me my start, so whether it’s subliminal or not, that holds a great deal of meaning. It has informed my career no matter where I’ve been, and hopefully it’s given me something special and unique, going in these different areas. At 16, I was very impressionable, so I definitely recognize what kind of effect New York City Ballet has had on me. There’s probably a lot that I wouldn’t even be able to identify, but is just inherent in how I go about what I do.

Did you choose your final role at ABT?

I did. It was a little bit about scheduling. Part of me would have really liked to have gone out with Giselle, but the slave Ali solo in Le Corsaire was one of the first I ever danced as a 12-year-old. I did it in black tights. I had my bowl cut. It’s also a part that’s tough from a virtuosic point of view. And I’ve got to go out there with no shirt on. But it seemed like it was appropriate, because it would be a challenging way to go out, and it suits my temperament and my spirit. It’s one of those roles where I have to go take some risks right up to the end, rather than being in white tights.

Were you worrying about your line?

I always worry about my line. At the same time, I’m lucky: I have the feet that I’ve been given. Hopefully they’ll keep pointing for two more shows.

Where were you when you were 12 and performing that solo?

That was for a summer workshop in Milwaukee, and my teacher was Paul Sutherland. It was one of those end-of-summer program shows, and he was like, “Oh, we’re just going to throw this solo in.” So there I was. Rocking out.

Are your injuries old, or are you in pain from something recent?

After four knee surgeries—and that was sixish years ago—that pain is there. I have two disc problems. I think that’s also why I chose the slave. You’ve got to have the warrior mentality, and I felt that after my surgeries, I did some of the best work of my career; and I never took the easy route. It seemed like, yeah—go balls-out and roll the dice.

How did you increase the rigor of your training?

When I got [to New Zealand] in September, I had a lot to wrap my head around, but I was moderately consistent with always doing some class or gym work. And then about three months ago, I took it to a whole other level as far as being consistently in class and upping the cardio. Diet. Being 39, a little more awareness is necessary. [Laughs] Right now, if I’m feeling good, I push, because I know I can break through and make progress. But at the same time, I have to be very intelligent in that I know I’ll feel it for a couple of days if I do too much. It’s that continual balance of trying to make progress while not injuring myself.

What happens after this?

I’ll be diving into creating a new Giselle production. So that’s cool. Physically, I figure I’ll probably want to keep moving or doing something, but I’m not sure exactly what. Probably something that doesn’t involve turnout. Right now, I’m so focused on preparing myself for these shows. It’s been somewhat emotional.

Are you sad?

Yeah. As I’ve said to my students or to dancers in my company, we have one of the greatest jobs in the world, and it’s really hard work, and it takes a lot of sacrifice. Do I want to stop dancing? No, man. I think being a dancer is the greatest thing besides being a writer.

Ha.

Being a dancer is one of the greatest things one can be. At one point, I was one of the best, and now I’ve become just one of the rest.

So it has to do with your identity, too?

Yeah. Not 100 percent, because I think I’ve always been grounded with other interests as well as a perspective in the world; but if I had a great show, I would never feel more elated or more high—or never as frustrated or upset if I felt a show didn’t go well. It has been a huge part of my identity, but you change, and I’m up for that. It is a time of reflection. Did I do enough? Do I have any regrets? I think I’m pretty cool in that I feel content about it, but could I have worked harder? All those questions run through my mind.

Why was Giselle so meaningful for you? Was that the first story ballet that you felt comfortable in at ABT?

It wasn’t so much that it was the first full-length that I felt comfortable in; it was more that I felt that’s where my artistic approach meshed with my technical approach and that basically, those things started functioning as one. It was about seven months into being at ABT, and I just needed that time here, but all that history that I had working in Europe and at City Ballet also contributed to that moment.

Now you’re working on a new production with Johan Kobborg. In the past, we talked about how you wanted to expand the part of Myrta. How is that going?

It’s going well. It’s now a whole different ballet than when we last talked. These things do take on a life of their own. I’m really pleased about the scenic design, because it is using the essence of [19th-century English illustrator Aubrey] Beardsley, but not in a literal way—maybe some motifs. What I like is that it’s really clean and sophisticated and expansive in its feeling and it also has a traditional sensibility to it, but one that is refreshed. The costumes would be of that period too, so it’s more of a Victorian time. As far as the story line, I don’t think we’re going to expand so much on Myrta, but we are looking to with Hilarion [the gamekeeper who is also in love with Giselle]; we’re giving him a little bit more, which creates more tension within the love triangle. I mean, Giselle ain’t broke. It’s a fairly sacred ballet, so act two will be very much respecting that tradition, but in the first act, I think there’s a little bit of room to maneuver. It’s been fun to build something this big from scratch. It involves a lot. I really am learning that a lot by doing this. The company’s culture is different, the nation’s culture is different, but I’m looking to embrace that and [change] what I think would be constructive to the company and programming. At the same time, I’m taking the initial period to observe and say, Maybe this isn’t how it’s done from my 20-odd years of experience, but this might make the most sense for the Royal New Zealand Ballet.

Do you feel like you have to cater to certain tastes or that you have to choose New Zealand choreographers when you’re commissioning new repertory?

Yeah. Definitely part of my job and my mission is to work with people in New Zealand, and that’s also because the government subsidizes what we do. But luckily, there’s stuff going on. It’s a small country, so the pool is quite different than it would be in the U.S. or in Europe; that kind of fascinates me, too. The country is really proud of its company, so to nurture and develop talent within New Zealand is good; and it’s good for me as well, because I’m not always going to have the resources to continually bring people in. We just had a big choreographic workshop with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, where they have a young composer’s competition. I put our young choreographers with their young composers. It ended up being pretty cool.

It seemed like your New York–centered program, “Three Short Ballets from the Big Apple,” went well, right?

It did. I was programming without knowing tastes or even knowing the company that well. I think the dancers were excited, because it was new for them as well. From the Brahms [Benjamin Millepied’s 28 Variations on a Theme by Paganini] to the Gershwin [Balanchine’s Who Cares?] to Adam Crystal’s music for Larry Keigwin’s [Final Dress], the program really did have a variety of perspectives. In New Zealand, we tour the entire country and each section has its own taste: Certain areas are really about tutus and tiaras, and other areas are more avant-garde; we try to program things that work on a number of levels, but are also progressive and innovative. That’s really intriguing to me. I can do some new things and take some risks, and people support it, because they really support the company. To have that real passion for a national ballet company is exceptional. When you come to town, people are there—they’re in it.

What is The Secret Lives of Dancers? Were you in a reality show?

I was, man. It was minute one. Stepping off the plane. That was pretty wild. They had done a season the year before I’d arrived, so this was the second one, and they did show a bit more about the dance elements and how a production is built. I was fresh off the boat and basically getting to know the company and finding my way. I was really more in observation mode. It is kind of wild. They’re talking about doing a third series, because it was really successful, and it did help boost interest in ballet; that’s a positive thing, but when they came about the third [installment], I said, “It would be good if my entire first couple of years as artistic director wasn’t all on film.” It does make a difference. It’s not that you’re less real or that you would really change anything, but with the camera there, it’s kind of exhausting. And you don’t know what they’re going to do with the material.

Could you forget that the camera was there?

I could, especially in rehearsals. I guess it’s just when you’re doing the interviews and they’re asking the same question ten times that you kind of just get like, Been there. The answer is the same. But it was really popular. The first season won one of New Zealand’s best reality-TV awards, so we might have another coming down the way. You’ve just got to do what you’ve got to do. [Laughs]

What has surprised you about being there?

We tour seven cities with each program. It’s a modern-day company in a modern-day country, but the style of that touring is quite a throwback, where you’re getting on a bus for five or six hours; you load in and tech on the day, and you might do the show and then boom, you’re on the bus or on a flight. I have to give a huge amount of respect to my dancers, because they’re resilient and always enthusiastic, and they’re working at a pace that would probably be very foreign and surprising to a lot of other companies. But they take it in stride, and they always deliver.

Do you feel like an outsider?

I came in toward the end of a production of Sleeping Beauty, which allowed me an opportunity to ease my way in. There were a couple of times when I addressed the company, and after a month or so someone came up to me and said, “Ethan, we can feel your passion for what you’re saying, and we believe in what you’re saying, but we just can’t understand you.” That’s pretty funny. New Zealand is a pretty cool place; it’s far away from family and friends, and obviously Gillian [Murphy, a principal at ABT and Stiefel’s fiancée], so that’s the hardest part. At the same time, Gill and I went to Milford Sound in Queenstown and saw stunning beauty all around. If you want to go off the grid and be alone, New Zealand is the place to do it. Or you can hang out in cafes and bars—it allows you that kind of luxury.

Do you ride your motorcycle there?

I haven’t. I haven’t bubble-wrapped myself, but I want to be as smart as I can. I want to make it to July 7 in the best condition I can be. But when Gill and I walked into Wellington Motorcycles, they were like, “Hey, are you the guy from the ballet company? It’s great to have you here, and anytime you want a demo bike or to borrow one for a weekend…” Just really chill. And New Zealand has the best coffee you have ever had. Ever. They have barista championships. They take it seriously. But when it’s gale-force wind and rain coming down sideways, you kind of understand why a nice cup of coffee goes down well.

I realize that your decision to stop dancing isn’t a happy one, but did you know it was right in your gut?

When I was a dean and balancing that with dancing, I learned it takes twice as much discipline and energy—and just to be a dancer takes enough in and of itself. Six years ago, they said I might never come back and do what I have been able to do, and you know what? I did it. I didn’t water anything down, I never cut back. Once I made the move to New Zealand, it just made sense that this would be the time. I am pretty much content. Of course, I would like to dance forever. This is also a celebration.

How so?

It’s not just about me. It’s about all those people who gave me the opportunities and coaching and teaching, as well as all of the dancers: I love dancers and respect the heck out of them. So for me, it’s also about being out there with dancers, as a dancer, one last time. I think it will be bittersweet, but again, it’s as much a celebration of whatever this all means as it is a sad thing. I try to look at it positively, rather than as a death. It’s a thank you. And hopefully what I do on July 7 honors all the work that people put into getting me to where I’m at and honors the dancers who I share the stage with, and the art form. Shit. [Laughs] You can’t forget where you started.

What do you think of when you think about where you started?

Oddly enough, although I’ve made some choices people think are risky, there definitely wasn’t a risk involved in going to City Ballet. That company dances, and you dance a lot. It was ideal for a 16-year-old kid to go in there and learn by doing. It seems to me an ideal place. I didn’t go into a company and hold a spear or push a cart around. I went in, and bang! I was dancing some masterpieces—in the corps de ballet, whatever, but still, you dance.

You dance your ass off.

Yes. And you dance a lot. And the fact that [Jerome] Robbins was still alive, and that I was able to be in the studio and work with him, is something I’ll never forget. That’s why I said to Peter, “Thanks, man. You gave me my start. Respect. You didn’t have to do that.” A 16-year-old dude. A little punk at SAB [School of American Ballet]. I’m really grateful that that’s the first place I went, because it gave me the opportunity to come into the other stages of my career with the perspective that made me special.

And a kind of daring?

Definitely. And a dynamic and aesthetic that’s mine. I think it gave me the versatility. I wasn’t so linear in my ability to move or musicality, or use of dynamics and energy. I had some stuff to learn, and I had to stretch myself in a different direction when I took on those things; at the same time, it meant I could make that shift from going into creative work, new work, and some of it pretty crazy.

Like what?

“Junkman.” That is one of them. [Choreographer Twyla Tharp] gave me a lot of room to maneuver, and I could infuse part of myself into that work. And I could do Bayadère the next night. And Swan Lake and [Mark] Morris and Don Q. It opens up a different thing, and it’s been about a pursuit, not perfection. I might not have thought that at 16. But it’s a pursuit. People were like, “Why are you going to go dance in Europe?” Well, because I thought it might provide me with an experience I would never have again. Or, “Why are you going to go from City Ballet to Ballet Theatre?” Well, because a career—for me at least—is 23 years. You can’t dance forever. It’s cool. You take all that in, and hopefully it will serve me well in my new role.

Have you been offered other artistic directorship positions?

Oh, no, no.

I can tell you’re lying!

[Laughs] Some people, when they’ve heard about different directorships opening, have been like, “What about that?” I was two months into the job. I like to commit to a good period of time with something, because I’m there to make a difference, and they’ve made an investment in me. I’m happy where I am. It’s allowed me to do things like Giselle. [Smiles] I have another new creation coming up. It’s a short one-act ballet. It’s a comedy to the music of Strauss. [Laughs] I won’t give too much away, but it involves beer. I’m in a good place. I can do that. I said to the board: “Look, if what I do is crap, I’ll be the first one to stop, but these things have been percolating for a number of years, and I just want to get them out there.” You know what? New Zealand suits me just fine. To have that support in these times, that’s golden. That’s choice, as they would say.

American Ballet Theatre performs at the Metropolitan Opera House (at Lincoln Center) through July 7.

You might also like

Read about the young ABT principal Cory Stearns

Tony Mendez—our favorite balletomane—talks about dance

Ethan Stiefel switched camps from NYCB to ABT; learn why Joaquin De Luz did it the other way around

See more in Dance