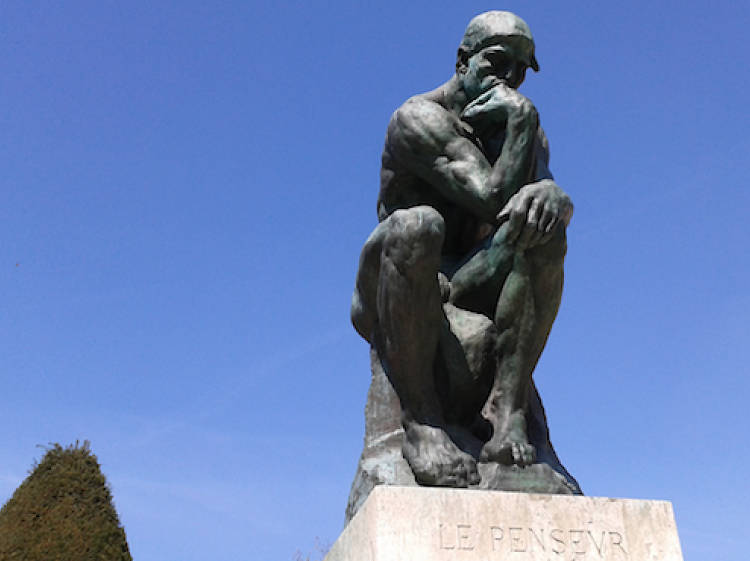

25. ‘Héraklès Archer’ – Antoine Bourdelle (1906-1909)

Upon its completion in 1909, this monumental depiction of the sixth labour of Hercules appalled one half of the public and fascinated the other. Its sheer scale was a factor, but it was the striking modernism of the statue, with its distorted anatomy and idealised lines, that really bowled people over. Twenty-six years after his arrival in Paris, Antoine Bourdelle had announced his emancipation from the lyrical style purveyed by his master Rodin. ‘Héraklès’ sealed his fame and set him on a career path that saw him become a teacher and mentor to the first generation of the 20th century: Giacometti, Brancusi, Maillol and their contemporaries. It remains his most representative work, and a tipping point in the passage of sculpture from the 19th century into modernism.