Most of us, if we found ourselves the subject of a heated global debate over our eligibility

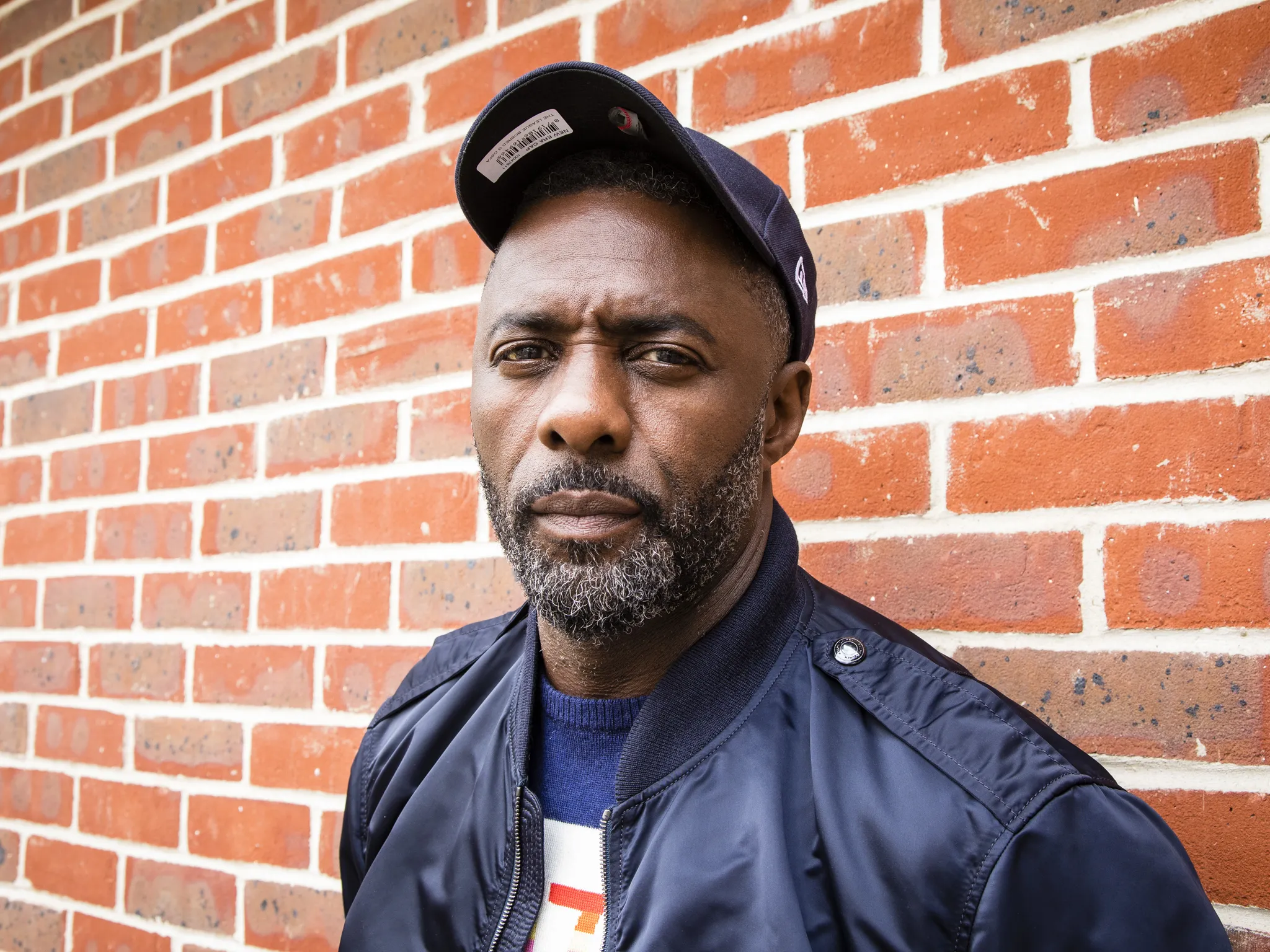

to play James Bond, would keep a low profile. Not Idris Elba. On a sunny afternoon, the 45-year-old star passes up the secluded interior of a privately booked Dalston pub for a beer outside in full view of yelling, waving fans.

As we talk, he barely seems to notice them. But that may be because his attention is fully focused on the imminent release of ‘Yardie’, a personal and pivotal film that marks his feature debut as a director. Adapted from Victor Headley’s cult 1992 novel, it tells the story of D (played by Aml Ameen), a Jamaican music obsessive-turned-drug dealer who encounters his brother’s killer in ’80s east London.

In one sense, it’s a departure for the man who made his name in front of the camera, breaking through as Stringer Bell in ‘The Wire’. In another, ‘Yardie’ – with its exploration of Hackney’s soundsystem culture – puts the East End-born, occasional DJ in very familiar territory.

A short walk from the site of his old council block near Queensbridge Road, Elba opens up about filming amid gangland violence in Jamaica, putting his memories of London on screen and, yes, the continued speculation about a certain martini-swigging MI6 operative.

What were some of the challenges you faced when you were directing ‘Yardie’?

‘I remember shooting in Kingston in a place called Rose Town. I felt a sense of audacity. How dare I come here, take this culture, turn it into part of a movie and then leave? I was concerned that the local dons were not happy about it. I was like, “Do they need to see the story? Is ‘yardie’ too much of a derogatory term?” So I said: “Okay, let’s be respectful. I want to hire locally.” We couldn’t even hire extras from another part of that area. They had to come from Rose because otherwise it would be gang warfare.’

Did things work out all right?

‘What was encouraging was [the dons] were kind of like [adopts Jamaican accent] “Idris make a movie? Cool. We call off. Ceasefire for three days.” And they did. The police told me that the minute after we left, there were gunshots. They were back at war. One kid had disrespected someone on the day we got there. As soon as we left, they shot him.’

What else was difficult about switching from actor to filmmaker?

‘As a director, you have to answer a million questions. As an actor, you just answer about you. Like, “I don’t give a fuck what everyone else is saying.” I now know it’s important to be collaborative.’

How surreal was it, making parts of Hackney look like they did when you were growing up?

‘I remember we shot in De Beauvoir and put all these posters up for the big [DJ battle] at the end of the movie. I just had this moment of: “I remember walking past this shit.” Growing up around here, when my dad used to drive me somewhere, I’d sit in the back and just look out of the window. So when I was scouting, it was so profound. There I was doing it again but looking for locations to recreate my memories.’

Being left in the car on your own was a big part of being a kid in the ’80s.

[Laughs] ‘If you were lucky, the window was open.’

Did being back here spark any specific memories?

‘One day, this kid came and found me on my new Tomahawk bike. He had his bike and we rode down to another [estate] building and he said: “Let’s go in the garages.” We left our bikes outside and went into a storage cupboard. He started smoking, lit a piece of paper that was on the floor and it went whoof! Up like that. He ran out and stood in front of the door. When I kicked it open he had run off on my bike and left me with his shitty one. I rode around trying to get it back for ages. The Tomahawk, man: that was a bad-boy bike.’

What are the things you crave most when you’re away from London?

‘The banter. English humour is really only appreciated here. My missus is Canadian and

she struggles. She’s like, “You guys are so dry.”’

You’re of Sierra Leonean and Ghanaian descent but ‘Yardie’ explores Jamaican culture. Did that cause you any trepidation?

‘I felt the pressure. But when Steven Spielberg made “The Color Purple” he felt a similar conflict. Kind of like “How dare I? I’m a Jewish boy.” There weren’t really many black people in any of his films prior to that and then suddenly he’s [adapting] this seminal text. I don’t think the director has to be particularly culturally embedded [to make a film].’

It ties in with the current debate about who gets certain roles, like Disney coming under fire for casting Jack Whitehall as a gay character.

‘Artistic licence is artistic licence. If an actor has the attributes to do something, they should be able to do it. They’re acting. You don’t necessarily have to be gay to play a gay character. Though you do have to be black to play a black character.’

There are specific sensitivities?

‘It’s like the debate about James Bond. It’s nonsense. It’s a fictional character. I’ve got mad respect for how Ian Fleming described him. He said he was a white guy, looked like this… That’s how it was written. But then there’s interpretation. If we were always bound by the confines that something has to be [one way], people would never have expanded on things

and come up with some of the most genius ideas.’

You’re going to be the producer, star and director of an adaptation of ‘The Hunchback of Notre Dame’. What interests you about that story?

‘It’s about someone who’s been cornered off because of the way they look, because of a disability. There’s something I can build out of that which makes him more heroic. That’s why it’s appealing to me. And it’s a challenge, bro. It’s a classic.’

‘Yardie’ opens Fri Aug 31.