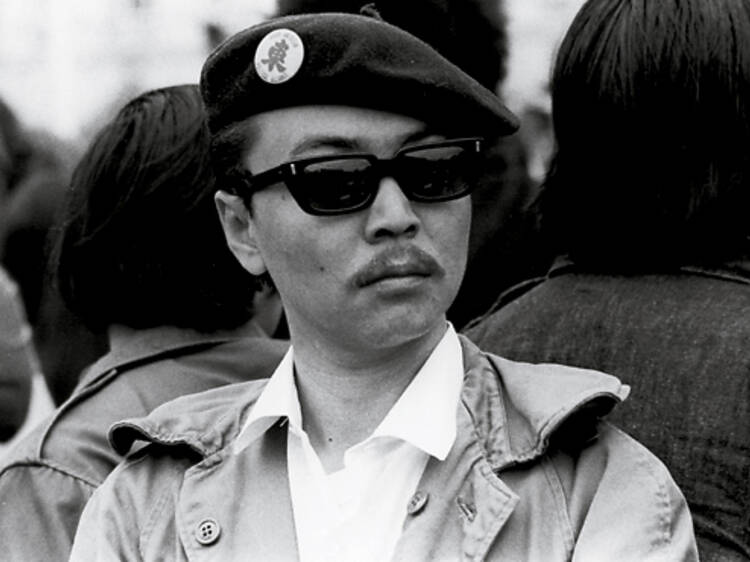

Training recruits on an Oakland tennis court, the Black Panther Party’s Japanese-American field marshal Richard Aoki would call out the cadence: “A .38 will set it straight. A .45 will keep you alive. A .357 will send them to heaven.”

Panthers cofounder Huey Newton “was appalled,” Aoki recalled 40 years later in Ben Wang and Mike Cheng’s documentary Aoki, which has its Chicago premiere April 8 in the 15th Annual Asian American Showcase at the Gene Siskel Film Center. “But he understood all this wouldn’t come about peacefully.”

Aoki was born in 1938 in mostly African-American West Oakland. After Pearl Harbor, like 110,000 other Japanese-Americans, Aoki’s family were sent to an internment camp. As a teenager, Aoki joined the black and Asian street gang the Saints. He witnessed the daily brutality Oakland police committed against minorities. “I could easily see the similarities between the concentration-camp experience and the conditions in the West Oakland ghetto,” Aoki says in the film.

He spent eight years in the Army and was a drill instructor when he turned down a reenlistment bonus as Vietnam was heating up, calling it “blood money.” At Merritt College in Oakland, he befriended Newton and fellow vet Bobby Seale, joining in pool-hall brawls and boozy rap sessions. When they invited him to join the Black Panthers in 1966, Aoki asked them “‘besides being crazy, are you color-blind?’ Huey said ‘the struggle for freedom, justice and equality transcends racial and ethnic boundaries.’” Aoki not only joined, he used his honorable-discharge card to obtain the Panthers’ first rifles and handguns from dealers, and oversaw their combat training.

Twenty-eight Panthers died in police raids on Panther offices in 1969 (including Fred Hampton and Mark Clark in Chicago). Aoki avoided the limelight. “If ‘the Man’ knew I was field marshal, they would have killed me,” he says in the film. Building alliances across ethnic lines, he helped lead the Third World Liberation Front strike that established UC Berkeley’s pioneering ethnic-studies program.

As a city-college administrator and counselor, Aoki worked quietly for decades to support poor and minority students. He finally went public about his revolutionary past after Newton’s 1989 murder by an Oakland drug dealer.

Cheng and Wang (whose Japanese-American aunts and uncles had been interned during WWII), were Asian-American studies majors at UC Davis in 2002 when they interviewed Aoki for the student newspaper Third World Forum. “We were trying to build a broader coalition among students of color,” Wang says. “Meeting Richard made it much more real and motivated us to get more involved.”

“He said none of the documentaries about the Panthers to date got it quite right,” Cheng recalls. “We said ‘why don’t you let us do a doc about you?’” Aoki took the students under his wing, bringing them to antiwar rallies and introducing them to Bay Area activist groups. After graduating in 2004, with no film experience, Cheng and Wang began five years of filming Aoki.

Cheng got an apartment in Aoki’s Berkeley four flat. Through their shared wall, he heard Aoki fall and break his leg after a stroke in ’05 and brought him to the hospital. After driving Aoki to speaking appearances, Cheng says, “he’d be as pale as a sheet.” In the weeks before his death last year, while undergoing dialysis, Aoki kept asking about protests over Bay Area transit police’s fatal shooting of an unarmed suspect in custody. “He was always engaged,” Cheng says. “When it came down to taking care of himself or doing political work, he’d choose the political work.”

Aoki screens April 8 at the Gene Siskel Film Center.