When watching this wise and moving modern parable from the former French colony and west African state of Chad, it’s worth bearing in mind that soon after director Mahamat-Saleh Haroun (‘Bye Bye Africa’, ‘Abouna’) started shooting in the Chad capital of N’Djamena, civil war eruped yet again and regularly threatened the safety of his crew as they continued filming. You’d never know it, though, from the quiet storytelling and subtle performances that define ‘Daratt’, which, like Haroun’s earlier ‘Abouna’, assumes an intimate focus and a gifted humanism but leaves the viewer thinking much more widely than just about the lives of the characters on screen. It’s apt, too, considering the threat to the film’s production, that Haroun’s purpose is to show that cycles of violence and predetermind patterns of war can sometimes be avoided by personal strength alone.

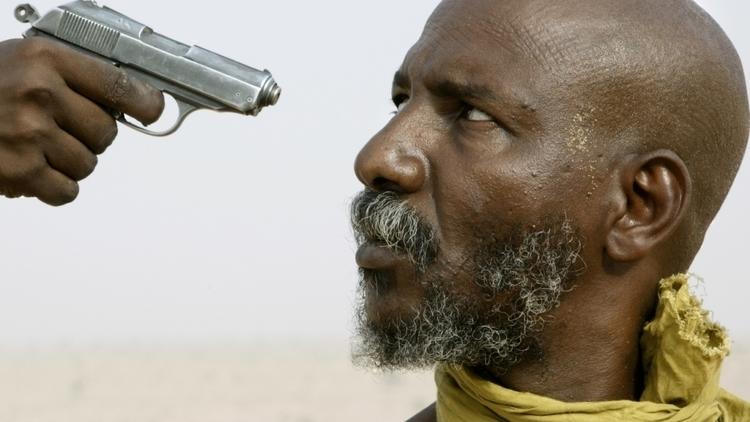

As in ‘Abouna’, the absence of a parent hangs over ‘Daratt’, but this time we know what became of the father of 20-year-old Atim (Ali Bacha Barkaï): he was killed during the civil war by Nassara (Youssouf Djaoro), an ageing, weak man who now lives comfortably as a baker in the Chad capital. As the film opens, the radio declares a government amnesty for all war criminals, yet Atim’s blind grandfather responds angrily by giving his taciturn, impressionable grandson a gun and sending him to avenge his son’s death. When Atim finds Nassara, he hesitates, and rather than firing the gun in his pocket he takes a job and a bed from Nassara. It’s now that the film’s most interesting conundrums kick in. Will he carry out his mission? Will he reciprocate the paternal fondness shown him by an unsuspecting Nassara? And is Nassara as unsuspecting as he appears? Blessed with a near-silent but always telling performance from Barkaï, Haroun dances around all these questions and more, but only allows an answer in the superb final moments: until then, the debate is as much with us as with Atim. Beautifully and simply photographed on location, ‘Daratt’ is a fine follow-up to ‘Abouna’ and confirms Haroun as one of Africa’s leading filmmakers, a committed humanist and a sly political commentator.