Maria

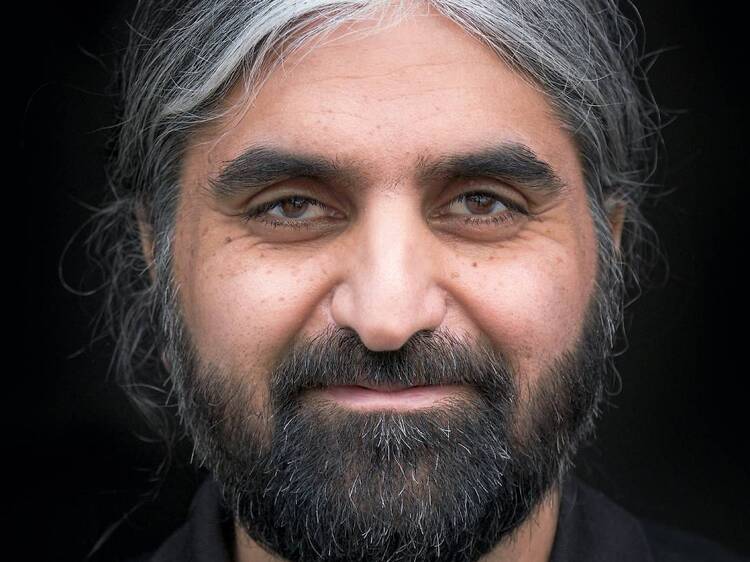

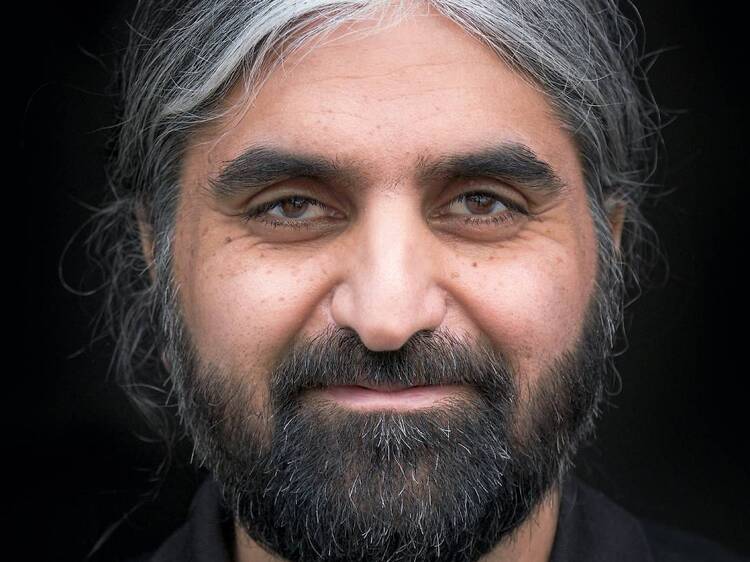

It might seem strange to say about an actress who emerged like a supernova, won an Oscar for Girl, Interrupted (1999), was nominated for Changeling (2008), and brought Lara Croft to life, that Angelina Jolie’s on-screen career has never quite hit the expected heights. With this musical biopic, though, she’s finally landed a role that will have audiences talking about her acting again. Directed by Chilean filmmaker Pablo Larraín, Maria casts her as American-Greek opera legend Maria Callas, a woman trying to rekindle former glories whose personal life, including a failed relationship with world famous socialite Aristotle Onassis, is cannon fodder for the world's tabloids. It wouldn't be wildly off-beam to call it a role Jolie has spent her life preparing for.

The script, by Peaky Blinders creator Steven Knight, looks back over Callas’s life in the week before her death in September 1977. It opens on the day she died in her house in Paris, which, with its marble busts, antique furniture and wall-to-wall paintings, looks like a room at the V&A. Shifting back a week, Jolie depicts Callas as a reclusive figure who is addicted to prescription drugs and whose loss of that formidable vocal range forced her into an unhappy retirement four years previously. Her chef (La Chimera’s Alba Rohrwacher) and butler (Pierfrancesco Favino) try their best to indulge her, but everyone realises she’s losing her grip.

It’s a role Angelina Jolie has spent her life preparing for

She hears voices. One