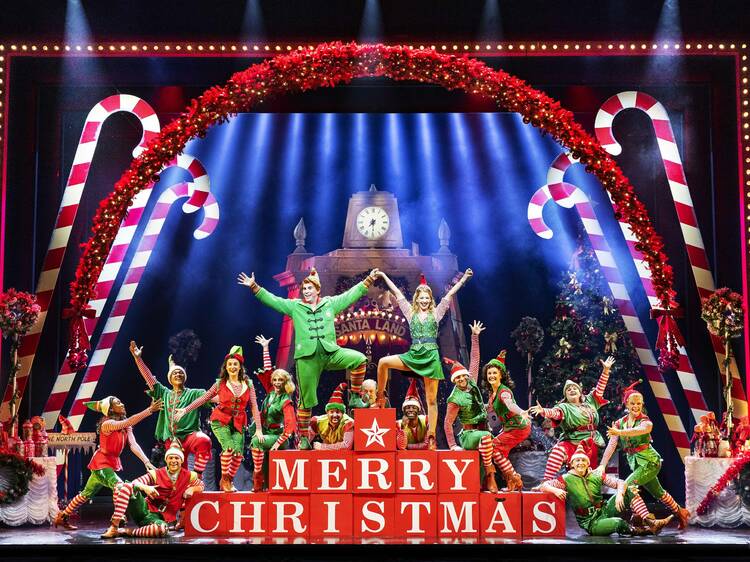

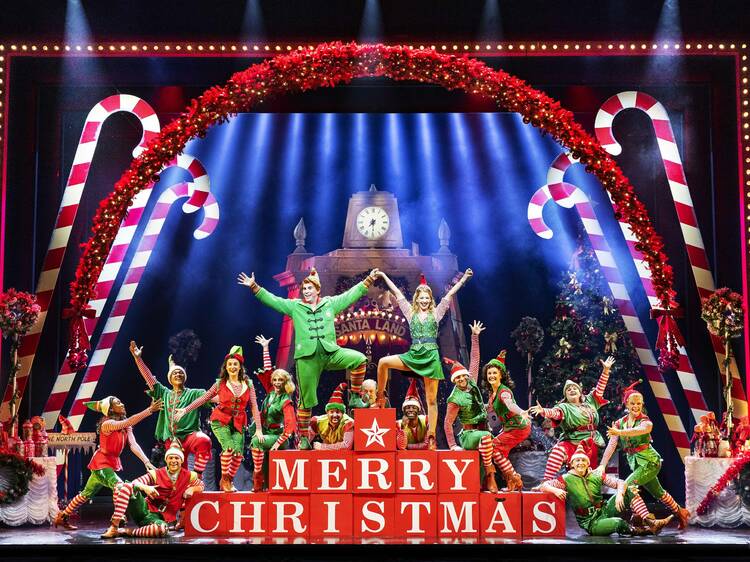

Elf the Musical

This review is from 2022. Elf returns for Christmas 2025 with a new cast that includes Joel Montague, Carrie Hope Fletcher and Aled Jones.

‘Elf the Musical’ rolls back into the West End with the same blunt-force charm as Buddy, its star. The last time this production was at the Dominion Theatre, in 2015, it was the venue’s fastest-selling show in nearly a century. It’d be a huuuge surprise if it’s not a success this time either.

Apart from a few tweaks and a couple of excised characters, the story largely follows the smash-hit 2003 Will Ferrell movie vehicle that’s now a perennial Christmas favourite. Titular hero Buddy’s Teflon-coated cheer can’t disguise the fact that he’s suspiciously tall for an elf. When Santa Claus breaks the news to him that he is, in fact, a human, Buddy sets out from the North Pole to find his real father in New York City.

The influences on the film and this show are legion, particularly ’80s fish-out-of-water classics like ‘Big’. Buddy arrives to find a fraught New York, full of Christmas as a sales pitch, but not with its spirit. His father, Walter Hobbes, is a harried, snappy publisher of kids’ books with no time for the young son he actually knows he has. (Buddy was the result of a college romance, whose mother died without ever telling Walter.) From initially stumbling onto the shop floor of department store Macy’s, to inveigling his way into Walter’s office and then his home, Buddy’s open-handed, child-like joy shows everyone he meets the t