It’s 3pm on a Sunday afternoon and I’m at the Rivoli Ballroom, the 1913-built dance hall in Brockley, south London. When I arrive, a group of mullet-sporting twenty-somethings dressed in vintage suits and loafers are smoking outside. Inside – with its plush carpets, red neon lights, crystal chandeliers and disco ball – the place is packed. But no one is drinking on the dancefloor; instead, the crowd is locked in to the music, moving to the sounds of Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell’s ‘Ain’t No Mountain High Enough’.

These punters aren’t just bobbing their heads and stepping from side to side. They’re properly dancing: performing steps that include a mix of shuffling, fast spins, high-kicks and split-legged leaps. Each mover appears in their own world as people trickle on and off the floor, some with their shirts drenched through with sweat.

This is northern soul dancing, which has been having a full-blown renaissance lately. In part thanks to social media (a recent TikTok from the Rivoli went viral, with two million views, while the popular Bristol Northern Soul Club also recently blew up online, now amassing more than 150,000 Instagram followers), younger generations are being introduced to the dance style that originated at all-nighters in Manchester, Stoke and Wigan in the late ’60s. Back then, British teenagers in the north of England adopted American soul music as a rebellion against the music charts. Today, young adults come to northern soul events searching for an inter-generational community, a proper dance, and a break from their phones.

But northern soul isn’t the only old-style social dance that’s making its grand return. Morris, line dancing and Scottish ceilidhs are all en vogue again, and the crowds are getting younger, and trendier. Where has it all come from – and does it signal the beginning of the end for the ubiquitous fist-pumping two-step?

Keeping the faith

At the Rivoli, I meet 18-year-old Stefan taking a break from the dance floor. Dressed in a white button-up shirt and tailored black trousers, they tell me they took up northern soul dancing a few months ago. ‘I also go to a lot of raves and techno events and always enjoyed the dance element,’ they say. ‘I watched the [2014] film Northern Soul and really enjoyed the music and flow of the dance’. Now, after teaching themself the moves at home, they’re a regular attendee of events at the Rivoli.

Fifty-three-year-old Max Licari runs Soul Stompers, a monthly northern soul party at the venue. ‘In 2022 the people coming [to my nights] were over 40,’ he says, talking to me over Zoom a few days later, dressed in a retro paige boy hat, yellow John Lennon sunglasses and paisley shirt. ‘But now, night after night, young people are coming. Every time they come back again and again, bringing more and more friends. It’s so cool.’

@bristolnorthernsoulclub Part 3 Add taps and kicks to you basic side step #steplecture #dancetrend #northernsoul #dancelessons #freetutorial ♬ original sound - BristolNorthernSoulClub

Licari came across northern soul ‘by mistake’ in the 1990s – and is excited to see its comeback. ‘The Rivoli has a great mixture of old school dancers and obsessives like me,’ he says. ‘I can see the evolution of the dancing. The youngsters now are incredible – I am shocked, they do all the acrobatics, spins and tricks.’

Highland hijinks

Two years ago, Scottish DJ Sarra Wild started the Hotland Fling: a mix of an electronic club night and a traditional ceilidh. ‘I don’t know if you’ve ever done Celtic dance, but it’s super f*cking fun,’ she says. The event takes over a community hall in Govan, southwest Glasgow, twice a year for a proper knees-up attended by all ages.

Typically, a Scottish ceilidh involves a live band (fiddles, accordions and bagpipes are all common), and a caller at the front, telling everyone the moves: skipping, spinning your partner and waltzing. The instructions are traditionally gendered towards the man or the woman. ‘In Scotland you are taught highland dancing in school,’ Wild says. ‘But it’s very heteronormative and usually happens at weddings or upper class events. I wanted to create a queer version that had black and brown people involved.’

View this post on Instagram

The Hotland Fling starts in the afternoon, with haggis, whisky, teas and coffees. It’s an all-age community event, where regulars attend for free and kids are welcome until 7pm. Highland dancing kicks off at 5pm, with three hours of ceilidh. Then, once the kids and elders have headed home, it becomes an experimental club night going on until the wee hours. It’s been a big hit – now, it’s not unusual for all tickets to be snatched up within a week. As for the crowd, it could be an ‘80-year-old granny’ to a young ‘trans femme’, according to Wild. The outfits lean towards ‘high fashion and chic’. Not surprisingly, there’s tartan galore, with punters creating their own takes on traditional clan get-up, with looks that range from super short kilts to full blown Vivienne Westwood-sque punk.

‘You have to be a bit silly, weird, and goofy to want to do highland dance,’ says Wild. For the health-conscious Gen Z, of which as many as 28 percent aren’t drinking, an all-ages gathering based around social dancing, where you get to have freeform fun without the pressure to consume lots of booze, is appealing. ‘People who came of age during the pandemic skipped clubbing all together,’ Wild says. ‘They’re into more sober day time events, connecting with community.’

Inclusivity wins

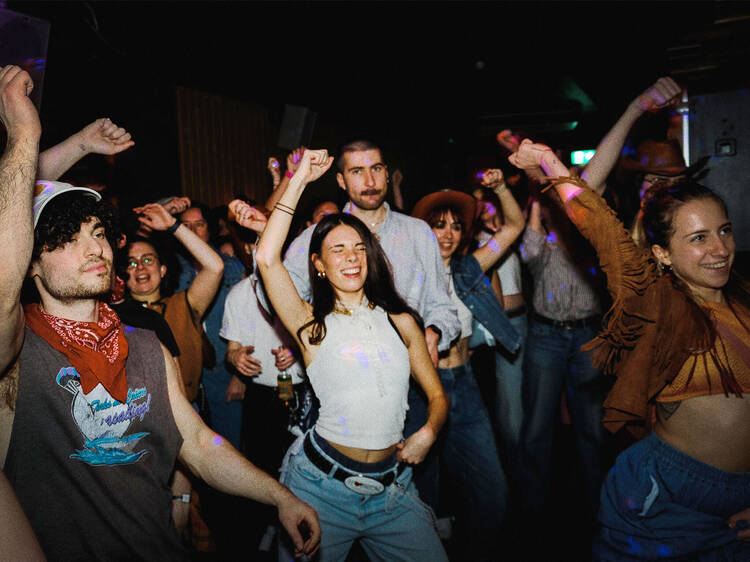

And then there are the rhinestoned cowboy boots, leather chaps and Chappell Roan tunes that are part and parcel of nights like Bonanza, Queer Line Dance London and the Cactus Club, which are forming a new glitter-soaked wave of LBGTQ+ line dancing parties in Britain.

‘It’s country without the “o”,’ jokes Sophie Ward, the founder of the north London-based event, nodding towards the mostly queer crowd. A typical Bonanza, which is held twice a month between the Boogaloo in Highgate and the Cock Tavern in Kennington, starts with a western-themed cabaret (‘drag singers, dancers, hula hoopers, we’ve had it all’) followed by a line dancing session, and then an open dance floor.

‘Dancing helps to form connections – it forces you to talk to different people, even if you wouldn’t have necessarily had something to say before,’ Ward says. ‘There’s a good hour of mingling [at the start]. It’s a really nice community vibe – relationships and friendship groups have started through Bonanza.’

Why line dancing? Ward points to the success of LA-based collective Stud Country. Now with 47,000 Instagram followers, Stud Country caught the eyes of queer brits with viral videos from their parties, which show trendy queer folk in fashionable outfits (think mini skirts, mullets and lots of cowboy boots), dancing to the likes of Pussycat Dolls and Kesha. ‘They made line-dancing really cool and queer,’ Ward says.

The modern Morris

In 2023 Time Out did a deep dive into the modern Morris dancing renaissance. Since then, this 500-year-old folk tradition, which involves jaunty skipping, hopping and a myriad of props including handkerchiefs, bells and wooden sticks, has grown even more in popularity.

Izzy Hancock, 30, has been a member of New Esperance Morris dancing club, based in south London, since 2019. ‘I needed a hobby that involved other people and moving around,’ she says. Over the past six years New Esperance has swelled in size, mainly attracting Gen Zs. ‘Most of the people who have joined recently have been in their early to mid 20s. The youngest member we’ve got is 21,’ says Hancock.

This is more about new ways people are connecting to their cultural heritage

Since joining New Esperance, Hancock has performed in London Pride multiple times, and ridden the Morris wave all over the UK, as well as abroad. ‘It’s definitely a post-Covid moment, and it seems like there’s an increased interest in folk things and music,’ she says. The club is part of the Morris Federation, which was founded in the 1970s with a focus on women as a reaction to the other organising body at the time which only allowed men to take part. ‘It’s always been important for the group to be socially progressive,’ says Hancock. ‘It’s been intentionally queer inclusive for a very long time.’

Culture journalist Emma Warren is the author of Dance Your Way Home, a cultural study into the social importance and history of nightclubs and dance floors. She compares the rise of folk traditions like Morris to the growing popularity of languages like Irish. ‘I think this is less about old-fashioned social dances, and more about new ways that people are connecting to their cultural heritage,’ she says. She adds that British passports got downgraded because of Brexit, so more Brits than ever are getting to grips with their ancestral and cultural heritage – whether this be through embracing age-old folk dances like Morris, attending intergenerational community events, or finding ways to modernise ancient traditions like Wild’s techno ceilidhs.

Dancing on

But what really is the appeal? ‘Structured dances, with a clear start and end point, offer a kind of scaffolding,’ Warren says, about the trend. ‘I can see why [they’re appealing], given that we’re still regaining social skills lost during the pandemic.’ What’s more, these sorts of dances are accessible. They don’t require expensive skills-based classes – either you teach yourself at home, or instructions to simple steps are given at the event.

We also can’t forget that fewer people are going clubbing because there are simply fewer nightclubs, Warren is keen to remind me. ‘Public space is being eroded left right and centre.’ These inter-generational parties, like Hotland Fling, are often held in community halls or DIY venues where the floors have been sellotaped down (according to Wild).

So could the rise of organised dancing hail the end of the two-step? This enduring move, which literally involves stepping from side to side, has become the staple of clubbers across Britain since dance music got massive in the ’90s. In official dance terms the two-step could refer to moves in country-western, ballroom and house styles, but in colloquial terms, we’re talking about the step you’re most likely to see the fishing-vest-clad, vape-clutching guy at Houghton festival execute with perfection.

As 2025 festival season goes into full throttle, it’s probably unlikely that we’ll see punters breaking into celtic dance at Field Day. But as Warren says, ‘dancing reflects the world, so it will always shift and change.’ The ubiquitous-in-nightclubs two-step or the humble dad dance aren’t going anywhere just yet, though the UK’s northern soul community is only growing, with new events popping up around the country every other month. As for the Hotland Fling, Wild has met dancers who have travelled to Glasgow from London, and even LA, to attend the gathering.

‘I think the younger generation wants these parties because they are real. I don’t see any kind of fake, or pretentious attitudes,’ Licari says. ‘At my nights people aren’t holding up their phones, people come to listen to the records we play. We don’t have time to make videos because people are dancing all the time. It’s beautiful.’