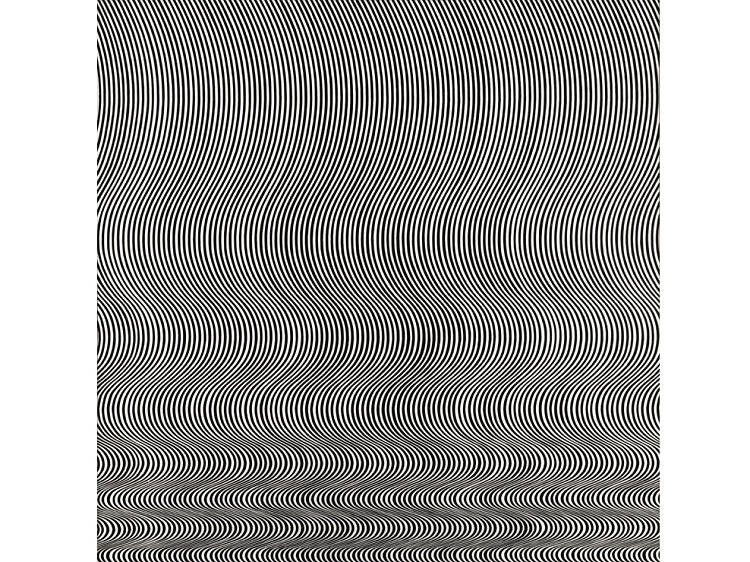

90. 'Fall' - Bridget Riley

WHERE CAN I SEE IT? This painting is part of the Tate collection but currently not on display. Check Tate Modern or Tate Britain to see when it will next be on show.

I LIKE IT See also 'Six Mile Bottom'

No, your latte hasn’t been spiked. This is an early classic by the dame of op art. Geometric patterns and repetition are key to any Riley composition and this work is like a snippet from a never-ending landscape of sound waves. By curving a single line, Riley is able to create a fluctuating sensation that has your eye darting all over the canvas field. It’s simplicity at its most visually complex.