This exhibition spans Clark's career, from 1960 to the present, and includes early photos that have never been shown before, collages and the Kids director's first foray into painting.

Larry Clark interview: “My father was a real asshole, which gave me a bottomless well to draw from”

The Kids director has a new art show with a familiar fixation on youth

When did you first begin taking photographs?

I started by working for my parents’ baby-photography business. My mother would go door-to-door, taking portraits of people’s babies in their homes. I never enjoyed it—but it put a camera in my hand!

At what point did you start to do your own work?

My first real photograph was of my best friend, Johnny Bridges, in 1961. I took it outside with a Rolleiflex camera. The show at Luhring Augustine begins with that portrait and continues to now.

How would you describe your subject matter?

I’ve always been interested in small groups of marginalized people who no one would know about otherwise. My photographs and films have always been about things that I wanted to see, but couldn’t find anywhere else.

Do you take a particular approach to capturing them?

I never just take a few photographs and walk away. I like to follow people for a long time. I photographed my friends in Tulsa for a decade for my first book. I’ve been photographing Jonathan Velasquez, who starred in my film Wassup Rockers, for 11 years now.

Speaking of your first book, why do you think Tulsa had such an impact when it came out in 1971?

It’s an epic! It captures a drug scene during a time when drugs were supposed to be a secret. Here was America projecting an apple-pie, white-picket-fence image, and then Tulsa comes out. It was a shocking revelation.

You released your first feature, Kids, in 1995. What led you into filmmaking in the first place?

All of my work had been autobiographical up to that point, and I didn’t want to do that anymore. I wanted to find out what was happening with adolescents in America at the time. I picked skateboarders because they were visually exciting, and also because they lived in a world where adults weren’t allowed. I managed to gain their trust and followed them for the next three years. Kids was based on the things I’d seen and heard over that period, which were compressed into a story that takes place over one day.

Why do you think you have this obsession with youth culture?

I didn’t have a happy adolescence, and to escape, I began taking drugs around the time I was 16. I wanted to be anybody but me, so I guess I became attracted to the people I did get attracted to because I thought almost everybody had it better than I had it. It’s a classic Freudian parent thing: My father was a real asshole, which has given me a bottomless well to draw from in the work.

Is that still the case with your latest work?

Everything is related, but I hope what I’m doing now is different, more complicated and more contemporary. I was a photographer and then a filmmaker. I’ve made nine feature films—soon to be ten. I’m also an artist who makes collages, and I recently started to paint.

Really? How did that start?

I was under a lot of stress while I was shooting my upcoming film, The Smell of Us, so because I don’t meditate, I started to paint. I discovered that it was like meditation: You forget about everything except the canvas in front of you. I’ve got one in the show, and I’m working on a couple more.

You also mentioned that you create collages, which you’ve been doing for a while. How are they different from your other work?

Collage offers a different way to tell a story with the photographs. I made my first collage in Oklahoma City in 1973, but I started doing them more regularly around the time that I was working on Kids.

There are a couple in the show that are multiple pictures of the same subject. There’s one, for example, of Brad Renfro. What was your aim there?

Yeah, that one is composed of all the photos that I took of Brad over a few days when he turned 18. Photographers don’t really want you to see all of the pictures that they’ve taken. They’d rather you see only the one great image. But photography is really about failure: You take 100 pictures, and 99 of them don’t get used. You’re really naked if you show every single picture you’ve taken. So I guess that was the point.

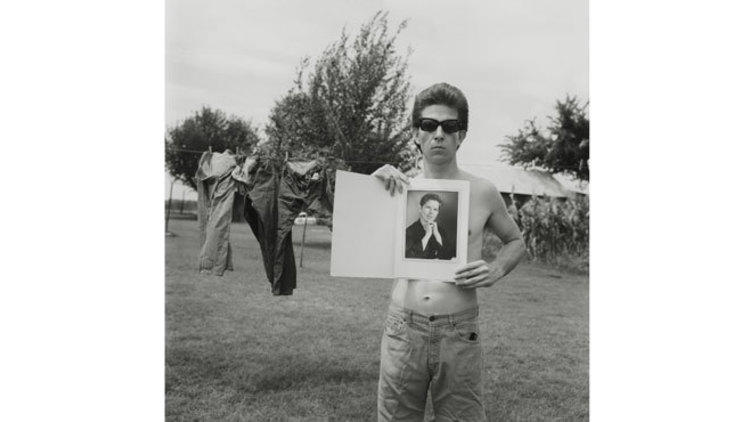

In January, you did a show at an East Village gallery in which you presented boxes of snapshots, each priced at $100. Those seemed like ripe materials for collage. Did you use them for any?

Yeah, there’s a self-portrait. It’s a black-and-white photo of me from 1963 surrounded by color prints of kids. It’s really out there. When I made my books I’d get to a point where I felt I really didn’t want anyone to see them; that’s when I knew they were ready. So when I finished this particular collage, I said to myself, I can’t show this. It’s too embarrassing. And that’s when I thought, I guess the show’s ready.

See the exhibtion

Discover Time Out original video