An already snow-blanketed New York awaits its third major snowstorm of the season in this digital photo, taken aboard the International Space Station on January 9, 2011 from an orbit of 220 miles above the Earth.

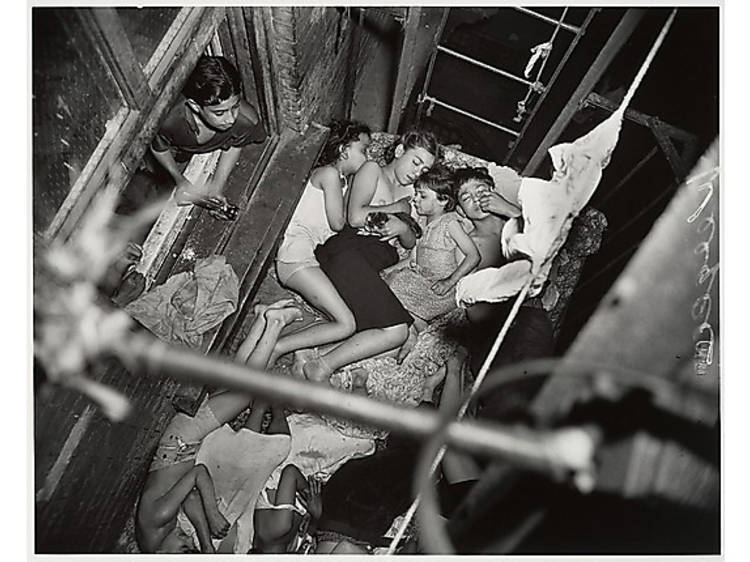

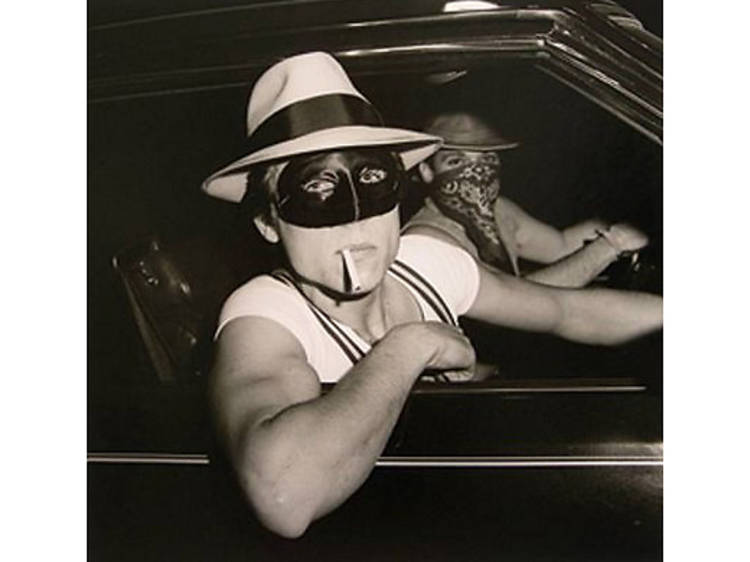

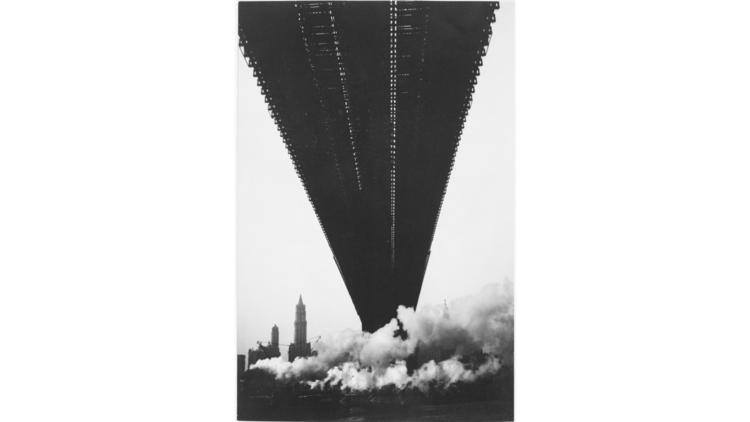

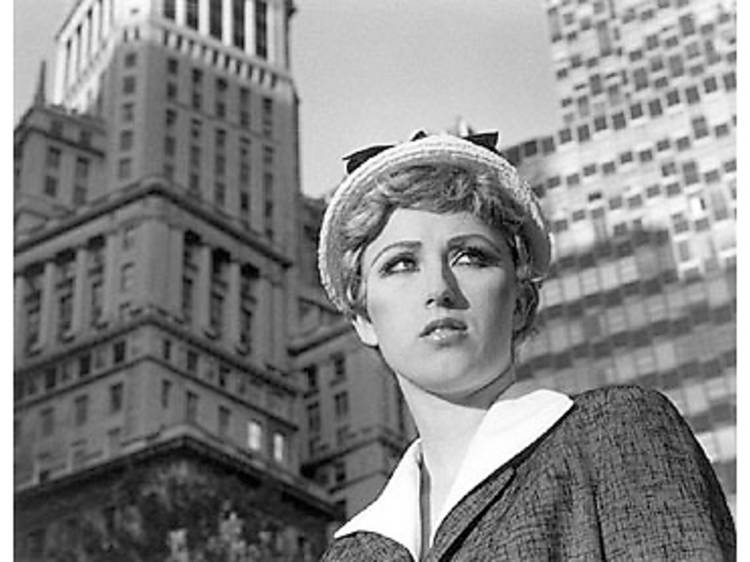

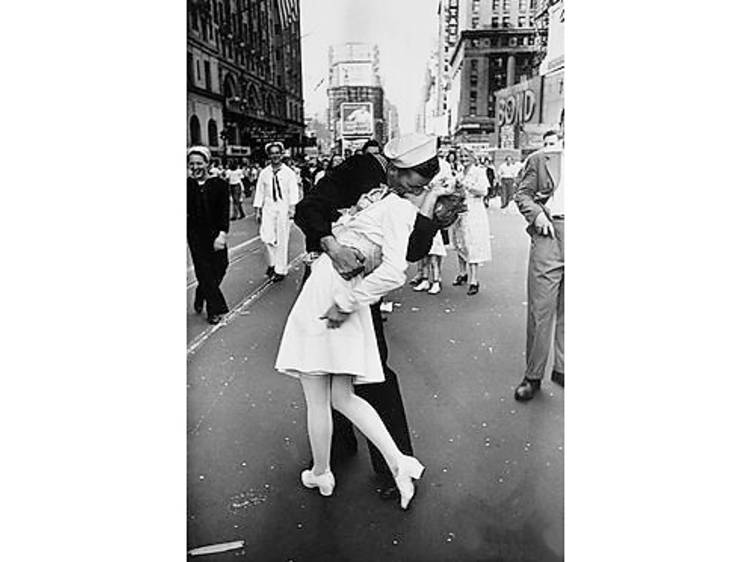

New York is one of the most photographed cities on Earth, if not the most photographed. This isn't just a matter of quantity (though, of course, there is that, given the number of snapshot-happy tourists) but of quality: Gotham has inspired legions of the best artists and photojournalists to capture it on film. Some of these images have become part of Big Apple mythology or helped to shape it, and if it were practical to bring them all together, they'd undoubtedly relate the epic tale of a metropolis driven by the both the best and worst aspects of human nature. It isn't practical, but it is possible to pick examples that tell something of that story, which is what we've done here.

Discover Time Out original video