The postmodern choreographer Douglas Dunn isn’t ashamed of being ashamed. His new Aidos, named after the goddess of shame and set to Bach’s lush cello suites, is full of technical dancing and doesn’t hide from emotion. “The fact that I’ve opened up myself to the pleasure of beautiful music is significant,” he says in an interview at his Soho loft, Douglas Dunn Studio, adding how fun it is “after so many years of being cool, to be warm.” In conjunction with the premiere at the BAM Fisher, he’s penned a limited-edition book describing his own feelings about shame with lines like, “Shame that my dancing is impotent to right wrongs; shame to consider that it would, should, could.” With Aidos, it just might.

How did you start thinking about shame?

It was the day I saw the word Aidos on the Internet. I looked it up, and it triggered something so strong that it opened up two veins: one writing and one dancing. Which doesn’t usually happen! These things came up as I was thinking about Aidos and shame, so I just spilled them.

How would you describe your writings?

They seem to have this sense of discreteness; they came up in pairs. Some of them are direct responses, like shame to be still, shame to move. But there is already sometimes an opposition in the single statement. Shame of doing something—why? I think this has a lot to do with feeling older.

That’s what I suspected, given entries like, “Shame at being an older dancer; shame at being ashamed of being an older dancer.”

You got that, too? [Laughs] Well, there are a few direct ones in there about my age and my figure and all of that slightly personal stuff. It’s like asking the question anew. What is dancing? What is living? What is being in New York? Everything’s up for grabs, because it’s not going to last forever. That sense of mortality comes in. My only worry was that it was too personal, but it doesn’t seem that way because it’s very suggestive. It was about responding to my own situation as a dancer and as a person and trying to not just maintain the eggshell attitude we all have in dance because it’s such a marginal arena to be in. You don’t want to put it down because it’s already vulnerable to being ignored or referred to as ridiculous or useless in our culture. At the same time, you don’t want to hide from all your feelings. Saying “shame this” and “shame that” was a way of letting it come up in a simple way.

What is your approach in Aidos?

It started in my mind when I went to the BAM Fisher, and the darkness of the space and the arena-like atmosphere really appealed to me, as does Danspace [Project], except that Danspace is so bright and has a high ceiling. Whereas at BAM Fisher, there’s nothing there. It’s like being inside of a tunnel. It’s not a place in the city, it’s a dropout into some cavernous unreality to me, which is great. I’m all for that. Going to hell.

How exciting—I rarely hear anyone talk about that space in a positive way.

I think it has its limitations, but this to me was right where I wanted to be. It took me somewhere. I went in there and said, Yes! I see a piece here. It’s very dancey, and I decided, to my amazement, to use the Bach cello suites. This is another moment where I feel, Really? I’m going to do that?

Why did you?

I was getting a shiatsu treatment, and the person I get it from played the Bach cello suites one day, and that was when that clicked in. I was lying there, thinking, I’m taking really good care of myself—oh, listen to that music. [Laughs] Always working! At first I wondered: Is it fair to pick and choose? I didn’t want to use the super famous ones. They’re just too familiar; people will start closing their eyes and humming along or something and not watch the dance. I asked [accompaniest] Ha-Yang Kim, “Is it musically legal to pluck one here and one there, or do you have to play them straight through?” She said, “Do what you want.” I got all the way through the dance until I said to myself, What about your solo? Are you going to have one? Can you still dance? I went to the most famous one [Suite No. 1 in G major]. It’s so beautiful. It’s actually not a solo. That’s the joke of this piece—there are three hearty men helping me.

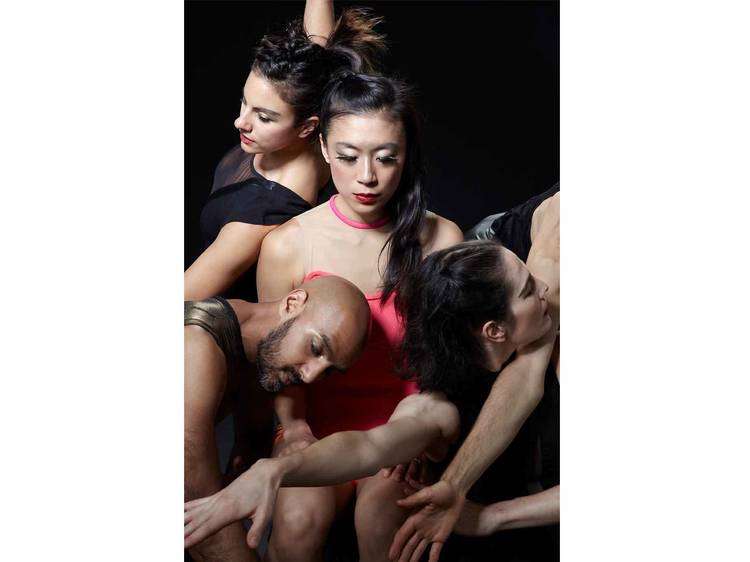

How exactly?

I dance around and they lift me up a little bit, they get me going again. I noticed that with the solos I’ve done the past few years, I always wanted to have some women onstage while I was dancing. This time, I wanted male energy.

Where will Ha-Yang Kim be in the space?

My idea for her and about the space was that she would be in the space. I had three stations for her. The first day she came [to play during rehearsal], she took the first space, and we did a few sections. It didn’t work at all. First of all, she’s very beautiful so you want to look at her; second, she’s doing another dance. I couldn’t feel the dancers! I thought, This is so unhappy for me. It was one of those ideas—once you see the reality of it, it completely falls apart. Now we’re working on how to have her in the balcony. I’m always interested in when my intuition is so off.

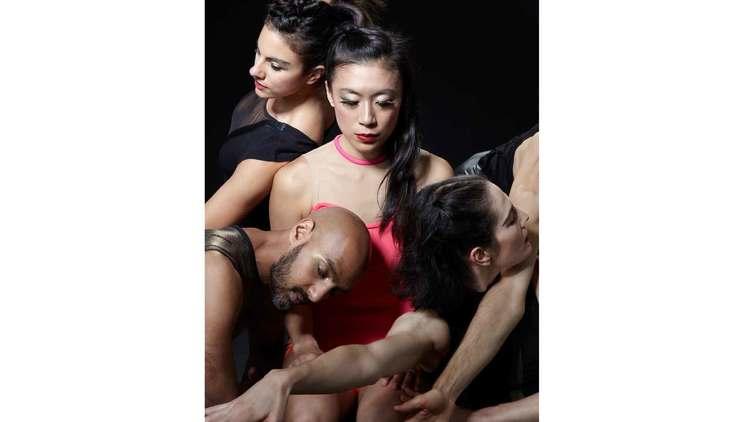

Will two women—Jin Ju Song-Begin and Jessica Martineau—play Aidos?

Nothing turned out literally. It was a strange moment in my life. I wanted a tall woman in my dance. I saw Jessica with Jin Ju as a pair and I thought, Oh that’s actually so much more appropriate for Aidos. We’re talking about a female goddess. I don’t care about the narrative line that much, but imagistically I liked the idea of the two of them dancing together. They’re always related. Sometimes obviously, sometimes less so. I am interested in duality—a splitting of a persona into two aspects.

Which is the idea behind the writing as well.

Yes! Isn’t that an amazing coincidence? In Cleave, suddenly, I wanted to use a lot of symmetry onstage. I’d been hugely enjoying not being symmetrical for 35 years. It gives it all away. In Aidos it’s coming up again, and it has to do with these two women and how I’ve, in some sections, gathered other people around them and worked in a symmetrical way.

And it’s full of dancing?

Yeah. I’m aware of it because I can’t do it myself anymore. Before it was all there, but I did it without thinking about it. Now I sit a lot in rehearsal. I’m very aware of the tempi; is it close or far? All the textural elements that used to operate more intuitively, I’m more conscious now.

Because you’re more outside of the process?

Yes. I’m watching and I have more time to think about it. There’s a lot of difficult dancing, which tests them in two ways: One is the more familiar way of stamina—doing a lot of jumping and fast moving and keeping up with it and getting inside it. The other is because of my physical state, I have to talk [through] the jump, I have to indicate. I can’t do the actual thing. But I’m also making material now where I am being in the body I still have to work with. The shapes in it are not as obvious; it’s much more complicated. I don’t want to say wiggly, but in that direction. Sinewy, small shifts of weight instead of being on center. I’m enjoying it a lot and the fact that the dancers can learn it now is thrilling to me, because now it means the range of the piece can expand. [Mutters] Getting old…

Does the change in your body really upset you?

It depends on the day. I’m so much more aware of my body in a way that I don’t particularly enjoy. The kind of awareness of the body to be able to dance, that’s fine. That lasted 40 years. But I remember the moment I started thinking, I shouldn’t jump anymore. Not that I couldn’t jump, but landing started to be dangerous. When I noticed that, it was a huge change in consciousness about dancing like, now I’m dancing and being careful? That’s not youthful exuberance.

How has your outlook about your work changed?

For many years, I didn’t get that many comments about my work in ways that reflected what I was feeling about it. In my book somewhere I say, “I’ve come to accept that the things I pay attention to in my work are not things that other people see in my work,” which is kind of a flat way of saying, What? [Laughs] But at the same time, it was important to accept that. But in the last few pieces—Buridan’s Ass, Cassations and Aubade—the response to my work has been more about an emotion.

Do you think that the emotional responses have anything to do with your using Bach?

I do. I think the fact that I’ve opened up myself to the pleasure of beautiful music is significant, not only in that then the music is there for people to enjoy as they watch, but it’s opened something up in me that I can’t analyze, which is making the dancing more open to emotion. In Cassations, we had beautiful opera all the way through. It was kind of embarrassing. Shame on that! But I was ready to do that and the people loved it, and I wasn’t doing it to make them love it, but it was fun. I don’t know what it means. I think it does have to do with some loss of idealism. I don’t want to make it a line, I want to make it a continuum. Again, age: Because I’m older, I feel differently about everything. I guess I want to have all the possible feelings around dance that I can imagine and these are the ones I’ve been avoiding. I’ve had them, but I’ve disguised them or I’ve covered them or sublimated them in some way. I just put them right into movement without letting it be seen that it is based on passion. So now some of that is just more overt. I don’t think I’ve compromised the movement. The movement is still difficult. It’s still sort of abstract, but the way I arrange it has changed and the kind of movement.

How?

[He demonstrates a position with one arm stretched up with the palm extended.] I used to avoid that because it’s too obvious. But now it’s not too obvious: It’s a good contrast with down. The full extension with some curviness instead of squareness.

Do you feel shame about dance?

When it comes to dancing, I almost prefer to use the word embarrassment. For me, it’s very rich now to bring up shame or at least embarrassment in relationship to everything that’s going on in my life. It doesn’t scare me. It doesn’t make me angry or sad, it just makes me feel like I’m seeing more, because I’m not limiting myself to, Oh I love dancing. I just don’t want it to become a kind of escape place, a simplicity—that’s all there is, so I’m content. I’ve never been content when I’m content. [Laughs] Discontentment is a way to proceed, and I don’t mind it at all.

See the show!

Discover Time Out original video