As Anthology Film Archives’ “The Glandscape Artist: Russ Meyer” makes abundantly clear, referring to the filmmaker by that last description is like calling King Kong a large, perturbed ape. Meyer didn’t just have a predilection for well-built anatomical balconies; he obsessed over freakishly large boobs, and traveled far and wide to find starlets whose D cups ranneth over. A beefy, mustachioed gent who looked like the uncle who always asks you to pull his finger at family reunions, Meyer was far from the only director of the era to fixate on well-endowed performers—there are so many ’50s movies featuring buxom blonds in torpedo bras that it’s surprising there weren’t more on-set impalements. But he was one of the few who, riding a cultural wave, milked an entire career’s worth of hits by being up front about his personal peccadillo. Most fans praise his movies now because the man knew how to make kinetic tabloid cinema with the best of them: Dig those crazy off-kilter compositions, the mile-a-minute verbosity of his voiceover narration, the submachine-gun speed-cuts, those impeccably photographed low-angle shots! Back then, however, people mostly showed up for the big bazooms.

Meyer learned how to use a camera as a war photographer on the battlefields of WWII and how to shoot the female form in all its glory as a postwar cheesecake shutterbug, both of which offered the perfect training ground for what would become his signature style: a constant sharklike movement and no-stone-unturned lechery. As he peddled smut pics to burlesque houses, the future auteur figured out that moving pictures of these topless dancers would sell better. So, with a borrowed camera and an old platoon buddy, Meyer made The Immoral Mr. Teas (1959) in four days; the story of a man who, thanks to a dentist’s novocaine shot (!), sees busty naked women everywhere, it invented the nudie-cutie genre and was the first exploitation movie to gross more than $1 million. Curiously, Anthology isn’t including this landmark skin flick in its survey; the sole entry from Meyer’s cutie phase being 1962’s Wild Gals of the Naked West—a loose collection of frontier vignettes that feel like live-action re-creations of dirty-joke Playboy cartoons. (Hopefully, Anthology will optimize viewing conditions for those screenings by placing random throat-clearing men in raincoats around the auditorium.)

The eight-film series also doesn’t include 1964’s Lorna, Meyer’s initial foray into “roughies”—exploitation films that larded the sex with heavy doses of brutality and sadism—but thankfully, it does feature the two other black-and-white, bump-and-grindhouse classics he made after that hit film. Mudhoney (1965) pits traveling city dweller John Furlong against fire-and-brimstone preachers, Felliniesque grotesques, hillbilly goons, the hamlet’s “upstanding” white-suited rapist and the quadruple charms of Lorna Maitland and Rena Horten (the latter, a German actor and Meyer paramour, couldn’t speak a word of English—so he made her character a mute). Imagine an old Li’l Abner comic strip reimagined as a Gothic nightmare, and you’ll have an idea of the perverse backwoods pulp this melodrama peddles. Motor Psycho (1965)—the title alone!—voyeuristically watches as a biker gang wreaks havoc on the lives of several small-town squares, including a veterinarian (played by the man who would become Moe Greene, Alex Rocco) and a Cajun trophy wife. A nasty little nugget that anticipated Roger Corman and AIP’s Hells-Angels-on-wheels cycle of B movies by almost a full year, the movie benefits from even jazzier, jumpier editing than usual and otherworldly, mono-monikered star Haji, who’d play a key part in Meyer’s next project—this time with women in the aggressor roles.

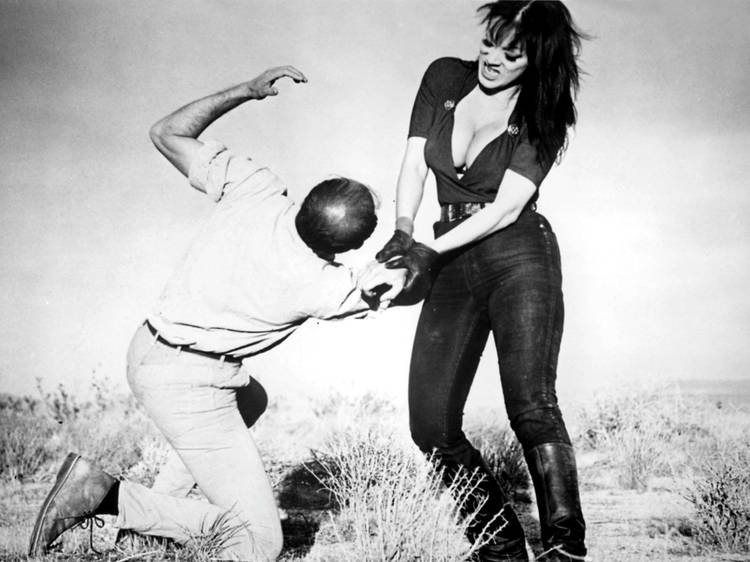

Waters once said that Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (1965) was “the best film ever made. It is possibly better than any film that will be made in the future.” The Citizen Kane of bisexual-go-go-dancers-on-a-rampage movies, Meyer’s undisputed trashterpiece starts with a baritone voice declaring, “Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to violence!” and only hyperventilates from there. The director may have cast more bosomy stars than Tura Satana, but he never matched up an actor with a role better; the half-Japanese, half-Cheyenne ex-stripper was born to play Varla, the leather-gloved leader of the pack who has a penchant for fast cars, karate chops, beatnik lingo and castrating sarcasm. Abetted by Haji’s girl-Friday-with-a-Chef-Boyardee-accent and Lori Williams’s Watusi-loving blond, Satana and her cohorts turn this “filmed in glorious black and blue” tale of badass broads run amok into undiluted, 200-proof delirium. Besides being, pound for pound, one of the most quotable celluloid pleasures ever made (“I am tied to this chair for life!” “BETTER YOU SHOULD BE NAILED TO IT!!!”), Pussycat represents Meyer’s fetishistic filmmaking talent at its absolute zenith. Bring the kids.

Despite the movie’s cult-classic status, Pussycat was one of Meyer’s rare financial flops; Vixen! (1968), however, was his biggest hit of all. The story of a young woman (the unstoppable Erica Gavin) prone to bedding anybody and everybody who crosses her path, the movie tapped into an audience ready for something stronger than the foreign-film exports that flashed a few nude scenes, but not yet open to hard-core porno chic. Cash registers ka-chinged and moral watchdogs went nuts, ready to prosecute Meyer on any number of obscenity charges; his defense—that the characters’ climactic political argument over Communism infecting radical politics constituted “social relevancy”—didn’t get him off the hook, but it also didn’t stop him from raking in the dough. Twentieth Century Fox took notice of Vixen’s grosses and handed Meyer the keys to the studio; the result, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970), would embarrass the studio for decades, even after camp aficionados reclaimed it.

Tied to Jacqueline Susann’s best-seller by name alone, it’s a moralistic tale of Tinseltown as a bed of sin inhabited by hermaphrodites, Hitler freaks and easy prey for SoCal predators, all done up in bad-trip vibes by a man who had little use for the age’s counterculture (barring the free-love part, of course). It’s best known now as the source for the Austin Powers–appropriated line “It’s my happening and it’s freaking me out!” and for being one of the rare screenwriting credits of a then-up-and-coming film critic named Roger Ebert. But this is actually Meyer’s last creative gasp, as after this, the movies got increasingly misanthropic, and the chest measurements of his starlets more cartoonishly outrageous. The barriers of permissiveness had already been knocked down, and Meyer’s moment had passed—yet as “The Glandscape Artist” proves, the man left behind a few timeless artifacts for the mammary banks.

"The Glandscape Artist: Russ Meyer" runs Aug 15–25 at Anthology Film Archives.

Follow David Fear on Twitter: @davidlfear