Instagram is full of the candy-coloured cottages of the Bo-Kaap, and you’ve likely heard the sonorous call to prayer drift across the city at sunset. But one of Cape Town’s lesser-known stories of faith comes woven with history and scattered around the Cape, hidden away amid vineyards, fynbos and seaside slopes.

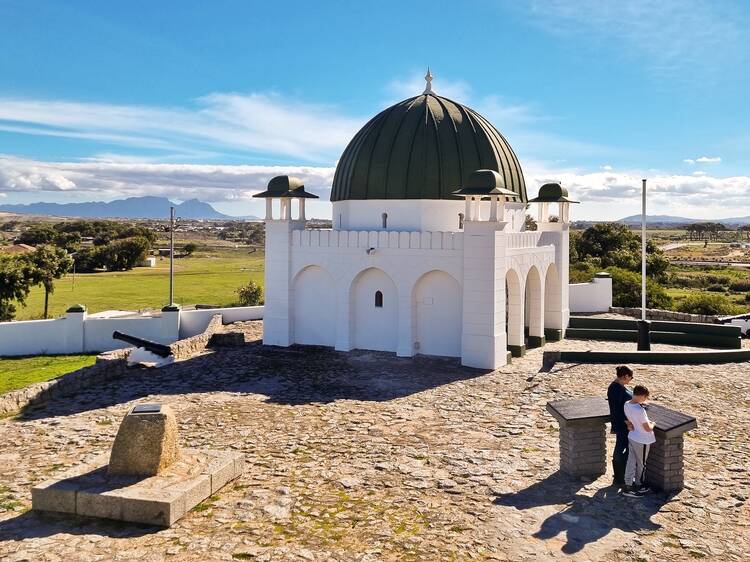

These are the kramats – also called mazaars – of Cape Town, which hold and protect the graves of Muslim saints, exiled to the Cape centuries ago. Taken together, they tell a textured story of landscape, community and history.

Kramats are the resting places of revered Islamic scholars and leaders – ‘auliyah’, or ‘friends of God’ – who were banished to the Cape by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) from the late-1600s. Many were influential figures in present-day Indonesia and Malaysia who resisted colonisation. Instead of imprisoning or executing them, the VOC scattered them to the edges of the fledgling colony at the Cape, banished forever from their homelands. Their simple graves later became shrines, today visited by the faithful and the curious alike.

Today, the kramats are far more than a simple list of historical sites. Plotted on a map, these tombs form a loose ‘circle of saints’ encircling Cape Town. And while the VOC once saw the Cape as a place of banishment, today the 23 kramats are part of the city’s living fabric; markers of faith and history. A place where memory and history meet.

The Dutch colonial rulers may have had little respect for the spiritual leaders banished from far-flung Batavia, but today the kramats are an integral part of life for the large Muslim community of Cape Town and an often-overlooked corner well worth discovering.