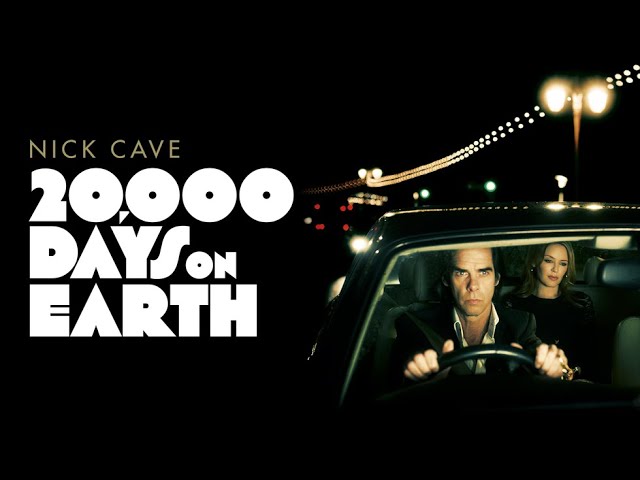

He’s trodden a singular path over the last 30 years as a musician, writer and all-round cultural provocateur, so it makes sense that Nick Cave has finally had a documentary made about him. What’s more surprising is how good it is. ‘20,000 Days on Earth’, directed by Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard, goes way beyond fly-on-the-wall rock-doc conventions to present a portrait of the artist without denting his enigma. We asked Cave himself about the making of ‘20,000 Days on Earth’ and the pitfalls of poor eyesight when you’re famous.

You’ve done so much in your career: singing, performing, writing songs and novels and screenplays. Was this film daunting?

‘Well, only in so much as it was going to be a film made about myself. I’ve never had any interest in the process of making such a thing. When I’ve been asked in the past, it’s just felt like something that’s going to get in the way, and I’ve never really liked a lot of music documentaries either.’

Are there any that you do like?

‘Yeah, I like that Led Zeppelin one [“The Song Remains the Same”]. It’s extremely flawed, obviously, but they were reaching for something beyond a “behind the mask” scenario. There are others. But yeah, I wasn’t especially interested in the idea initially, until Iain and Jane came to me with something that looked like it was going to be about something else. And, you know, I ended up feeling more like an extra in a film about something else entirely. Maybe that’s not really true, actually. Hang on. Forget that. But it felt like the film had a larger purpose than “telling the Nick Cave story”.’

How much control did you have over it?

‘I had final edit. Allowing me that freed me up to do anything I liked – anything that they asked, actually. I was extremely dubious about starting the film with me in bed: It just felt like a very vulnerable scene to shoot, and it didn’t even seem like a very good idea. But we had this policy where we’d try things out, and they didn’t need to be used. And it seemed to work.’

You’ve worked with Iain and Jane a lot before – presumably that must have helped?

‘We’re friends, and I’m a fan of their work, and I really like the stuff that they’ve done with me – particularly stuff outside of the standard rock videos. Iain and Jane’s videos that they did with me [for the Nick Cave And The Bad Seeds singles “More News from Nowhere” and “Midnight Man”] came out of that rock video place which I really dislike, but the work around that stuff is really extraordinary, when they’ve been free to do their own thing. It always feels very comfortable to have them around. Weirdly, we still remain friends after they made the film. That’s not often the case with me.’

How much of the film was scripted or rehearsed, and how much was improvised?

‘Well, all the scenarios are fake, in the sense that they are set-up scenes. The shrink’s office, the archive [visit], the idea that I’m driving around in a Jaguar: It’s all artifice. But we thought that within that, I would be able to relax enough to be open about things. They knew that I wouldn’t be that way if they just walked into my house with a camera. It just wouldn’t have happened. I wouldn’t have allowed it.’

But some of the locations are real, aren’t they? Isn’t that actually your house?

‘No, that’s just a pretend house! Well, my bedroom is real. The opening scene of me waking up in bed was actually filmed in my bedroom, because they wanted to have a nod towards the album cover of “Push the Sky Away”, which was shot in my bedroom.’

So that’s the only real location in the film?

‘Yeah. Everything else is a set, I think.’

Even your band mate Warren Ellis’s house?

‘Yeah, it looks like the house that Warren would live in. In fact, it does actually look quite like his house! But he lives in Paris.’

There are three interview guests – Ray Winstone, Blixa Bargeld and Kylie Minogue – who appear in your car throughout the film. Whose idea was that?

‘It was a combined idea. We just talked about who the best people would be, and we got the people we wanted.’

I was going to ask if there was anyone you wanted but couldn’t get.

‘Well, they initially had an idea that it would start with Ray, and as the film progressed, the car would just keep filling up with actors, all having a discussion about acting. But that was just too difficult to organise.’

Did you know Ray Winstone before he starred in ‘The Proposition’, which you wrote?

‘No, I met him there. We see each other around a bit, and we get on really well. He’s impossible. He’s just the way he appears to be, really – and some actors aren’t. Some actors are just unrecognisable from the people they play. But Ray feels like a character actor who is really an embodiment of the people he plays.’

On the subject of acting: Do you feel like you’re playing Nick Cave in the film?

‘No. No.’

It’s all natural.

‘Yeah, I mean, it’s just the sort of stuff that I do. But a fabricated situation teases out more truths than a real situation, because that’s the kind of situation that people like me operate in. I didn’t describe that very well. Make it sound good. In fact, while we’re at it, could you do me an enormous favour and take out all the “kind of”s from what I say?’

Is that a pet hate of yours?

‘Oh man, sometimes [interviewers] don’t. It’s like, “Oh, for fuck’s sake – do your job! Edit!”’

Noted. So what do you get out of this project, apart from maybe a boost to your profile?

‘Well, there’s that for sure. But I think, quite genuinely, what I got out of it was that I was able to consider certain things that I did, because I had to write about them. I’ve always taken the creative process very much for granted: If I sat down, it happened, and that’s the end of it. I’ve never looked at it in magical terms or mythological terms. You just do the work and you finish, and the next day, you do the work. But this film made me articulate certain aspects of the creative process that allowed me to continue in a more effective way.’

How serious are the voice-overs you do in the film about creativity? You’ll say something that sounds very sincere, then undercut it.

‘Well, that’s just what I do. That’s just me. There are obviously humorous elements to what I say, but there needs to be a place for the serious stuff to come out.’

I was reading a recent interview and you said there were certain things you can’t do because you ‘can’t be fucked being Nick Cave in that situation’. What sort of things? Do you mean like going to the supermarket?

‘I don’t really go to the supermarket, to be honest. But I think what I mean – and this is quite true – is that it’s easier to stay at home. There’s a certain expectation that goes on if you go out the door.’

You mean people coming up to you?

‘Not necessarily, but there’s a more-than-ordinary feeling of self-consciousness. I think everyone feels self-conscious on some level when they’re in public but… I mean, I’m pretty good with it. I know other people who find it extremely difficult. It’s not that you have to keep up some kind of charade; it’s just people see you and recognise you.’

You don’t get the comfort of anonymity.

‘I have a terrible memory for faces, and I constantly make mistakes with people I know quite well. I don’t recognise them. It often happens. So I went through a period of embracing everybody that came up to say hello, like, “Hey, yes, I know you!” But very often, I’m kissing and cuddling someone who then says, “Hey, can I have your autograph?” After a while you have to build something around yourself to protect yourself.’

We see your twin sons in the film for about 20 seconds, and we see your wife just as a glimpse at the beginning. Did you not want them in the film, or was that their choice?

‘It was definitely Susie’s choice. She had to be coaxed into doing anything, and she did so very reluctantly, to be honest. The kids couldn’t give a fuck one way or the other.’

So it wasn’t a conscious decision to keep that side of yourself private?

‘I think it’s not really what the film’s about. The film is certainly about my relationship on an abstract level to my muse, let’s say. To those people around me who inspire me – let’s forget the “muse” word. And Susie drifts in and out of my songwriting and everything that I do. She is a ghostly, spiritual presence within songs, so her not actually being in the film is, weirdly, the way it actually is. She’s an ethereal type. The shot with the boys I really like a lot, because it is a shot of a father with sons, but it’s also a shot of a father and sons looking into a camera, which is set up where the screen of the TV is. So even that aspect is artificial, suggesting that it is impossible to take off the mask, even in the privacy of your own home.’

So you’ve seen the final film?

‘Yeah, in the cinema, I’ve watched it once. It’s not something that I do – I don’t listen to my records back – but there’s a sense of remove with this film, where I can actually sit back and enjoy it. Even though it’s about me, I don’t feel implicated, in some way. Maybe I am, but I don’t feel it’s my film.’

Would you say that the film is aimed at the general public?

‘I don’t know. You mean, would anyone be interested in it if they weren’t familiar with what I did?’

If they were just into films, not Nick Cave.

‘Well, someone was telling me that they heard two people outside a screening going, “Hey, that was really good, but I’m confused: Where was Nic Cage?”’

‘20,000 Days on Earth’ opens in UK cinemas on Fri Sep 19.