[category]

[title]

In the footsteps of Mary Shelley’s classic spine tingler on the Royal Mile

‘Slop’ meant something different in 1600s Edinburgh.

Rather than some AI nerd trying to ‘improve’ on a Studio Ghibli film, back then it was something to dodge when you were wandering down the Royal Mile. ‘Gardyloo!’ went the cry – a Scottish bastardisation of ‘Gardez l’eau’ or ‘watch out for the water’ – as someone chucked a bucket of piss (or worse) on the cobbles outside.

I know this fact because it features prominently on every tour and exhibit during my two days in the city’s Old Town. Nowhere in the world is as proud of its historic lack of plumbing as Edinburgh. And is it possible to know too much about plague? I’d say no, although, haunted by a close encounter with a raven-beaked plague doctor during our evocative candlelit tour of The Real Mary King's Close, a ghostly 17th century rabbit warren, my eight-year-old took a radically oppositional view.

It’s like someone has turned up the goth on this elegant necropolis

As autumn turns to winter, it’s like someone has turned up the goth on this elegant necropolis. The Fringe Festival in August celebrates a different, more cultural side to the city; now, as the days shorten and locals begin to hunker down for biting November evenings, the city’s dark past spills out like guts from a cadaver. The Royal Mile echoes with tales of murder and misadventure, stolen corpses and witch hunters, torment and tribulation.

Down the hill at the kitsch yet oddly unnerving The Edinburgh Dungeon, you can find actors cosplaying as pitiless judges, torturers and cannibals of yore with a conviction that’s borderline method. Victor Frankenstein and his monster get their own spooky section, too – ‘Mary Shelley’s Monster’ – another reminder of the rich literary past of the first ever UNESCO City of Literature.

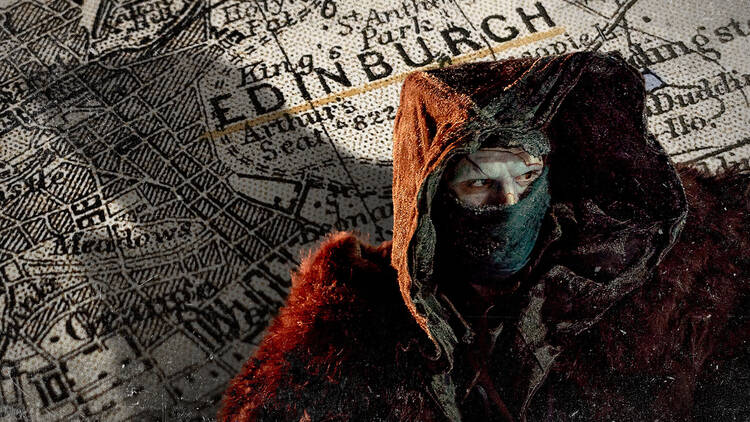

It’s the perfect setting, in other words, for Guillermo del Toro’s vivid, gruesome and eerily romantic new take on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

‘It’s pretty startling to see people hanging’

A renowned scaredy cat, I’m braving these ancient terrors to find out how Shelley’s classic found its spiritual home in Edinburgh – and del Toro’s new movie is the place to start.

The Mexican auteur behind Pan’s Labyrinth began to pull those two Auld Reekie threads – art and anarchy – together over two weeks filming on the Royal Mile in September 2024. He went further afield – across Scotland, England, and onto Ontario – but the cobbled thoroughfare lends grandeur and a macabre streak to his film’s mid-section. Shelley’s 1818 novella features Edinburgh only in passing – there’s a reference to Bernard’s Well in Stockbridge when Victor Frankenstein travels through the city on his way to Orkney – but del Toro plugged right into the Old Town’s gothic aura. ’We took him to every possible close [off the Royal Mile],’ remembers Frankenstein production designer Tamara Deverell, ‘of which there are, like, a hundred. We’d looked at the Czech Republic, Hungary, all kinds of countries from across the world [as our location], and whittled it down to Scotland – mostly because Mary Shelley spent so much time there and it's so evocative of her Frankenstein.’

I’m shown the movie’s three Royal Mile locations by Rosie Ellison of Film Edinburgh, the council’s production-supporting film office. We walk from Bakehouse Close in Canongate – once used in wildly popular fantasy series Outlander and now transformed into an 19th century alley running with butchers’ blood – as well West Parliament Square in the shadow of St Giles Cathedral, which was used as a bustling market, and nearby Lady Stair’s Close.

The latter is the setting for a macabre gallows sequence in which scientist Victor (Oscar Isaac) sizes up the soon-to-be-hanged for body parts from which to forge his creature. Inevitably, it’s not as far-fetched as it appears. ‘“Resurrections” of the dead – digging up bodies – to supply the medical school and its anatomy lectures were so frequent in Edinburgh that guards were hired to watch over the cemeteries,’ Ellison tells me.

Lady Stair’s Close is one of the Old Town’s more expansive spaces – more square than close – but it’s still easy to image Victor Frankenstein stalking furtively through it on the hunt for a limb or two. Team Frankenstein had to warn its residents of the plans to build the gallows before filming. After all, no one enjoys waking up to a mass execution – even a Hollywood one. ‘It’s pretty startling to see people hanging,’ notes Deverell.

‘Being an author in the 19th century wasn’t reputable’

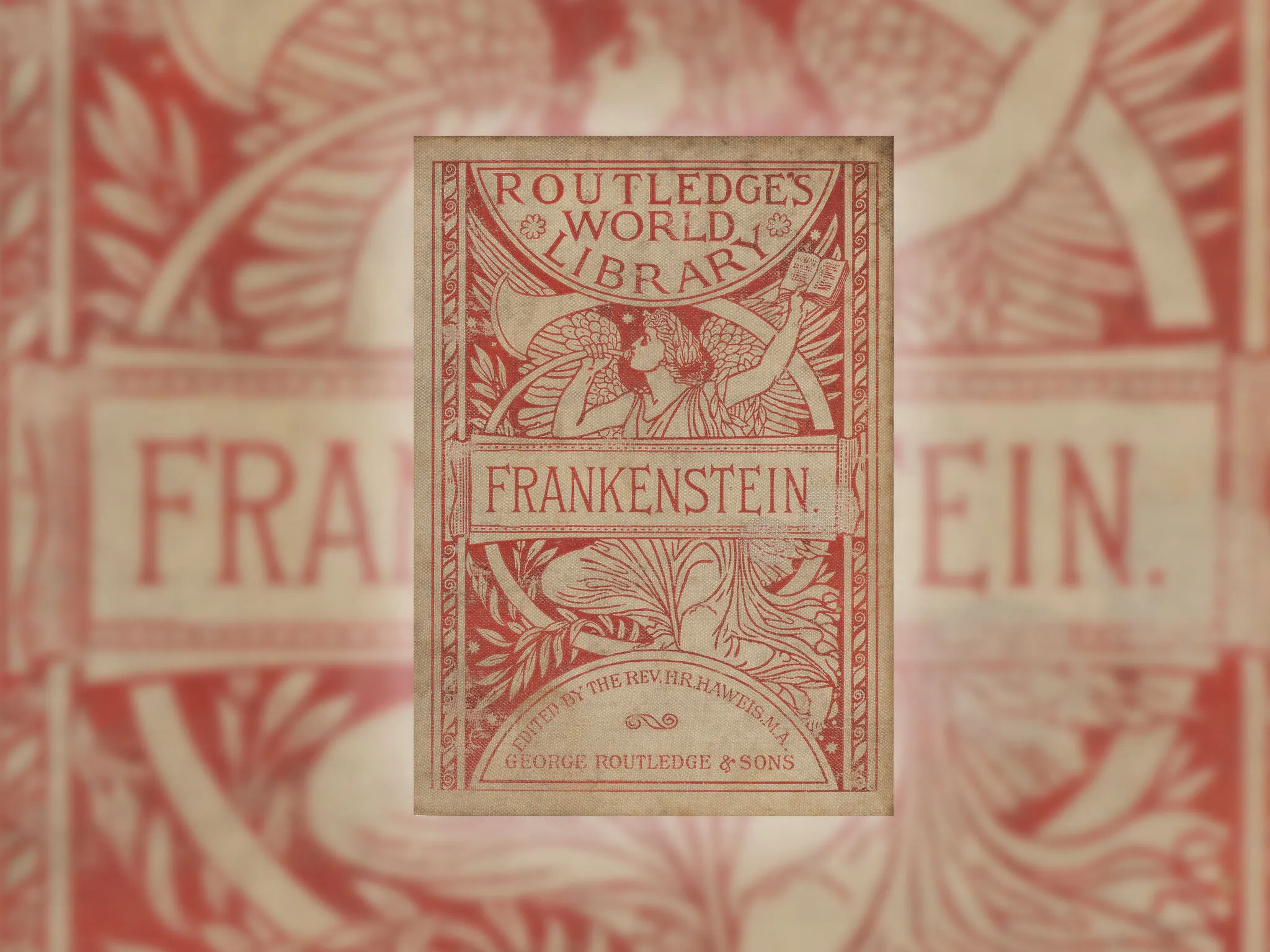

A steel bolt’s throw from a Frankenstein themed bar (try the Corpsey Colada, the Dr Henry Clerval pizza, or, if you’re feeling really brave, haggis) and five minutes walk down George IV Bridge you can find del Toro’s source material. The National Library of Scotland is home to several early editions of Mary Shelley’s work of gothic horror, along with letters and correspondence between her and her coterie of friends and associates, including husband Percy and Lord Byron.

In one of the Romantic era’s worst cases of unconscious bias, Walter Scott’s review of the anonymously published book assumed that Frankenstein had been written by her husband. ‘Being an author in the 19th century wasn’t reputable, so [anonymity] was about keeping your respectability,’ library curator Kirsty McHugh tells me. She points to the delicately phrased letter in which Mary Shelley gently informs Scott that she, in fact, was the bad bitch who’d got Frankenstein down.

The library will be exhibiting its Shelley and Frankenstein treasures this month, but the 20 or so letters by the writer are always available for locals to peruse (just put a request in via the website). The pop-up exhibition will also showcase Scottish literature’s sizeable debt to Mary Shelley with first editions of Muriel Spark’s 1951 biography of the London-born writer, Child of Light, and Alasdair Gray’s Poor Things, recently, of course, adapted into Yorgos Lanthimos’s Oscar winning comedy.

Mary Shelley could just be the most influential twentysomething in cinema

She wrote it after a summer by Lake Geneva in 1816 with Percy, Byron and the half-forgotten John William Polidori, literature’s John Deacon, starting aged 18 and finishing it as a 20-year-old. Considering it’s since been adapted into something like 420 movies, beginning with Boris Karloff's 1931 Universal classic and ending with del Toro’s new blockbuster, she could just be the most influential twentysomething in cinema.

Shelley wrote most of her landmark tale in Bath and was said to have been inspired by Dundee where she lived for a time. But Edinburgh’s spirit courses through her great work of romantic horror like a winter’s downpour through a Royal Mile close. To be here as the darkness falls and this ancient thoroughfare glows a ghostly orange, it feels like her Monster has finally achieved the feat that has forever eluded it on the page, and on-screen, and found a home.

Time Out was a guest of Visit Scotland and Old Town Chambers, Edinburgh.

The Frankenstein display takes place for one day only at the National Library of Scotland on Friday, November 7 from 11am-4pm. No booking is required and entry is free.

Discover Time Out original video