Don't Sleep There Are Snakes

Pass my Elephant-in-the-Room gun, I’m putting this one down nice and early. Yes, ‘Don’t Sleep There Are Snakes’ would have seemed a far more original and intriguing proposition before Simon McBurney dropped his epic Amazonian odyssey ‘The Encounter’ on the world. Yes, their themes are similar. And their concepts. And, actually, so are their conclusions, and even some of their phrases. But that shouldn’t matter, because Simple8 are the ensemble behind rough-hewn, brilliantly imaginative adaptations of ‘Moby Dick’ and ‘The Cabinet of Dr Caligari’, so, however unfortunate their timing, there should be plenty here to be excited about.

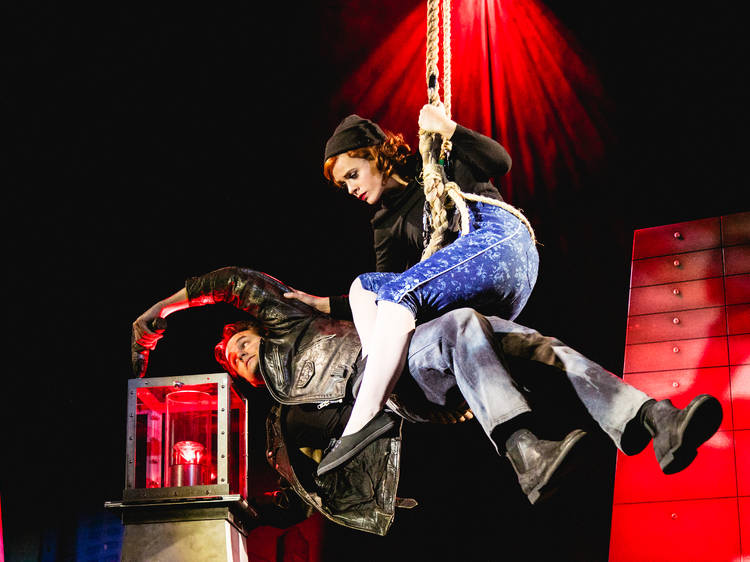

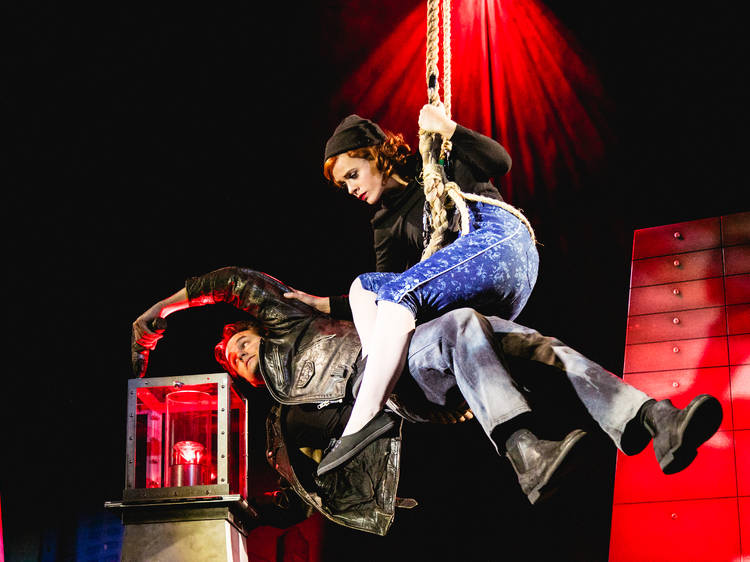

Unfortunately, there’s barely a scrap of the magic that made those earlier productions so intoxicating. In their place is sparse and wordy documentary theatre that’s neither intriguing nor poignant enough to justify its paucity of visual or human interest.

In this true story of linguist and missionary Daniel Everett, whose time spent with the Pirahã people of the Amazon rainforest caused him to lose his faith in both God and Chomsky, Simple8 fail to make either of these fractures carry the slightest emotional resonance. Their script meanders like a lazy tributary, and their trademark blend of lo-fi ‘poor’ theatre techniques, music and movement bob to the surface so rarely their use feels almost tokenist.

The company uses intonation cleverly to suggest several interlocking spoken languages while speaking nothing but English, but outside of that, this